Is Europe getting complacent? [Gas in Transition]

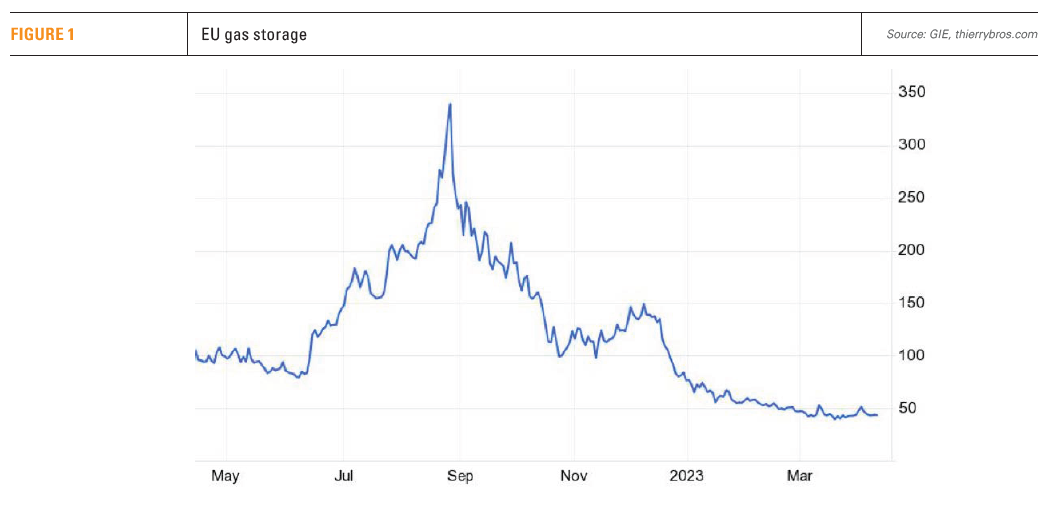

Following the declaration by European energy commissioner Kadri Simson at the end of February that the gas battle has been won, Europe has descended into a period of optimism. The winter is over and the risk of disruption in the supply of natural gas is over, for now. EU gas storages are exiting winter over 56% full by the end of March – the best position they have been since 2018 (see figure 1).

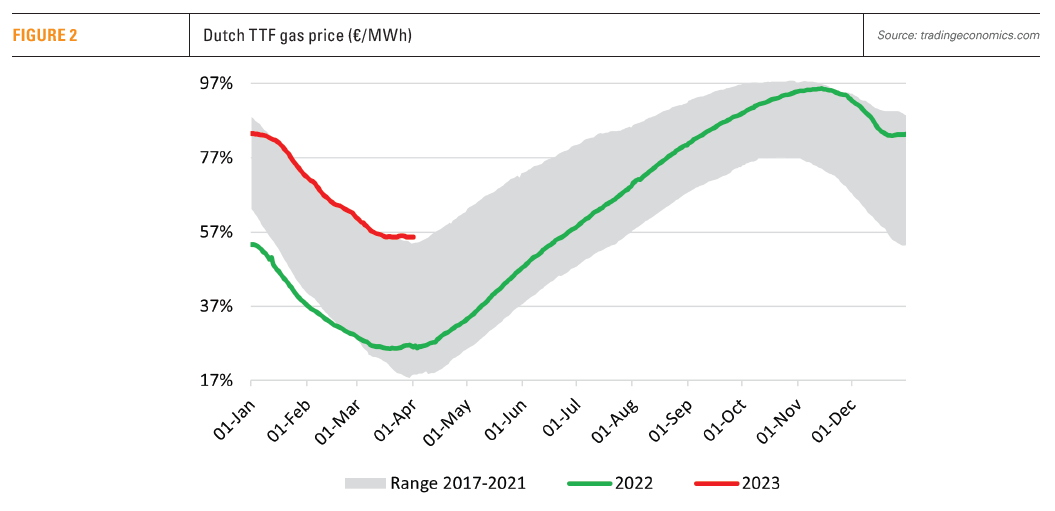

As a result of this and plentiful supplies of gas and LNG, prices have fallen from their peak last August, at over €340 ($373)/MWh, to under €45/MWh by mid-April (see figure 2).

To be fair, Simson went on to say “The test is not over. We have just won the first battle and there is still a long fight ahead of us.” She added that to further strengthen its hand, the EU needs to work on diversifying its energy supply, deploying more renewables, reducing energy demand and ensuring it has sufficient gas in storage to get through next winter.

Undeniably, though, the EU made it through the winter without suffering supply disruptions, despite the reduction in Russian gas exports to Europe – a major achievement. A combination of mild weather – Europe had the second warmest winter on record – demand reduction because of the very high prices and the economic slump and timely policy actions led to a 55bn m3, or 13%, reduction in gas consumption in 2022. Record additions of wind and solar power also helped.

The reduction in Russian pipeline gas supplies was largely replaced by the import of LNG, mostly from the US. European countries, including the UK, imported 121 million tonnes of LNG in 2022, an increase of 60% compared to 2021.

But that was achieved by paying a high price. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the cost of Europe’s LNG imports more than tripled in 2022 to about €180bn. With its aversion to signing new long-term LNG supply contracts, Europe bought the additional LNG largely on the spot market at high prices - over 70% of its LNG purchases.

To a certain extent Europe was somewhat lucky that China, under its zero-Covid policy, saw a 20% reduction in LNG demand in 2022, with part of the LNG contracted in the US by Chinese importers redirected to Europe – something that is highly unlikely to be repeated in 2023. This averted competition and kept prices lower than otherwise could have been.

There was also another price to pay. Europe consumed more coal for power generation, up 7% in 2022, pushing power sector carbon emissions up by about 4%.

Nevertheless, the combination of these developments led to a substantial reduction in Europe’s gas demand in 2022, high storage levels at the end of winter and substantially lower gas prices. This recipe is unlikely to be repeated in 2023, hence the many calls during the last few weeks for caution and avoidance of complacency.

Avoiding complacency

Most energy outlooks show global gas and LNG demand rising over the foreseeable future. BP’s New Momentum scenario, designed to capture the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently travelling, shows global demand increasing all the way to 2050. Shell’s corresponding scenario, Archipelagos, does the same.

With COVID restrictions over, China’s economy is growing. The country set a GDP growth target at around 5% for 2023, but some economists expect it to rise by 5.8%. Economic performance data from Q1 2023 show strong economic rebound, with March’s performance even better than that of January and February. This was confirmed by Bloomberg, reporting a 14.8% y-o-y increase in Chinese exports in March.

Europe’s economy is also expected to pick up in 2023. The European Commission (EC) expects EU economic growth of 0.8% in 2023, up from the 0.3% it predicted in November.

Increased economic activity is leading to increased energy consumption. BloombergNEF expects China’s primary energy demand to grow by 5.3% this year, compared with 2.9% in 2022. Energy Aspects expects Europe’s LNG imports to rise in 2023, but well below the 2022 levels. It also expects the TTF price to rise to about €70/MWh by the end of the year, compared to less than €45/MWh mid-April, and stay high in 2024, and up to 2026, driven by increased competition for limited LNG on global markets.

Bruegel states that “assuming limited Russian exports continue, and weather conditions are typical, demand up to October 1, 2023 must remain 13% lower than the previous five-year average. The EU should therefore extend its demand-reduction target, which is currently set to expire on March 31, 2023.”

It should also be noted that during the first half of 2022 on average Europe was still importing about one-third of its gas needs from Russia, but by the end of 2022 this dropped to about 40mn m3/day. As a result, assuming that flows of Russian gas to the EU continue at current levels, Russia would be delivering on average about 40bn m3 less gas in 2023 than in 2022.

Having said that, in March Kadri Simson urged “all member states and all companies to stop buying Russian LNG and not to sign any new contracts with Russia once the existing contracts have expired.” Last year the EU imported around 20bn m3 of Russian LNG. That would put more pressure on securing LNG from other sources in what is expected to be a tight market.

Having said that, in March Kadri Simson urged “all member states and all companies to stop buying Russian LNG and not to sign any new contracts with Russia once the existing contracts have expired.” Last year the EU imported around 20bn m3 of Russian LNG. That would put more pressure on securing LNG from other sources in what is expected to be a tight market.

Bruegel expects the EU will continue to compete internationally for LNG cargoes, and will remain vulnerable to global dynamics. The emerging strong economic growth in China is likely to make this more challenging by further tightening markets.

In addition, there are already warnings that Europe is facing another year of drought, especially southern Europe: Italy, France and Spain. According to the EU Joint Research Centre Europe and the Mediterranean region “could experience another extreme summer this year.” Last year drought impacted hydro and nuclear power generation, with the deficit having to be provided by using more natural gas.

The IEA has also warned that if Russia cuts gas deliveries, China buys more LNG from global markets, and the 2022/2023 winter is unusually cold, Europe could face fuel shortages. It recommends that it is crucial that governments keep up efforts to save energy and boost renewable energy.

EC’s position is that provided gas storages fill to 90%, and the EU achieves continued demand reduction by 15% and continued high LNG supplies, there should be no supply gap in 2023. Too many ifs that already appear to be facing challenges. Certainly, Europe should not get too comfortable with “low” gas prices.

These developments justify the calls for caution and avoidance of complacency, especially by politicians.

Europe’s approach to gas

The news on April 12 was that Sinopec took a 5% stake in a train with a processing capacity of 8mn/metric ton/year in Qatar’s LNG expansion, making it the first time China has directly invested in Qatari gas. It also underlines China’s position as Qatar’s largest LNG buyer. The driver behind this is clearly to bolster China’s energy security.

Compare this with the EU's at best unclear policy towards gas. The strategy in RePowerEU is to reduce gas consumption by 30% by 2030 and continue reducing it on the way to net-zero by 2050. Despite this, the EC is sowing confusion by also saying that natural gas will be needed into the 2040s and claiming that there is nothing stopping companies from entering into long-term contracts.

Such a strategy and confused messages send the wrong signals to European utilities, who are unwilling to sign long-term contracts, and to oil and gas companies that require assurances about future security of demand, in other words long-term gas-purchase contracts, to facilitate future hydrocarbons development. With Europe’s current strategy this will not be forthcoming any time soon.

Mike Wirth, Chevron’s CEO, warned recently that a premature effort to transition from fossil fuels has resulted in “unintended consequences”, including energy supply insecurity. With variable, intermittent, renewables in mind, he warned that western governments have made a global oil and gas crunch worse by doubling-down on climate policies that will make energy markets “more volatile, more unpredictable, more chaotic.”

The global goal remains to switch to green energy and eliminate carbon emissions. But with no clear pathways to an energy-secure future completely reliant on renewables and hydrogen in the near to medium term, gas and LNG have an important role to play in Europe.

The EU is targeting biomethane production to reach 35bn m3/yr and green hydrogen production to reach 10mn mt/yr, with a further 10mn mt/yr of green hydrogen to be imported, by 2030. However, their production is still being scaled up and it is unclear that it will reach anywhere near these levels by then.

In fact, Shell’s Energy Security Scenarios report, released in March, expects that it will take time for hydrogen to make an impact. It reaches 1% of industrial final energy use in 2044 in Archipelagos, a scenario that looks at how things could evolve if current trends and known policies continue. The IEA expects hydrogen to provide only 2.5% of total power by 2050.

Renewables intermittency is still a challenge and, until the problem of long-term electricity storage is resolved, it will remain a challenge. A recent report by the WMO showed that climate change is causing prolonged periods of slow winds, making wind energy unreliable, requiring back-up by gas, as happened in 2021 when wind energy was down by more than 30% and is likely to happen this winter. Similar problems apply to drought, impacting hydropower and nuclear – the energy shortfall in 2022 was covered by using more natural gas.

Uninterrupted, secure and reliable electricity supplies can be ensured only with back-up from fossil fuels, preferably gas.

In their communique on 16 April, the G7 energy ministers recognised that “investment in the gas sector can be appropriate to help address potential market shortfalls provoked by the crisis…in line with our climate objectives and commitments.” Will the EU follow suit before the next crisis? It remains to be seen.

Unless Europe realises this, it will sleep-walk into the next energy crisis later this decade, as the need for gas to make up for non-performing renewables becomes apparent. Without new production, and without enough long-term LNG deals, gas supply will be tight, with gas and energy prices going up…again.

Challenges

Energy security is expected to remain a top priority in 2023 at the expense of energy transition and climate change. That puts priority in securing adequate and affordable energy supplies.

Accelerating Europe’s transition to cleaner energy could provide the answers. But with intermittency still a problem, the road to cleaner energy will be long and arduous, with natural gas needed for a long time to come. Eventually Europe must recognize this and accept that new long-term gas contracts – greater than 15 years - required to justify the necessary investment in oil and gas E&P and infrastructure, will be essential. Europe needs a more secure supply strategy than just buying on the spot market with little control on prices and quantities.

But right now the EU is going in the opposite direction. EU countries intend to push for a global phasing out of fossil fuels among their climate diplomacy priorities this year, including at COP28.

As European gas and electricity markets become difficult again by the end of 2023, the EU will redouble its efforts to accelerate the development of renewables.

It should be remembered that less than 30% of the EU's gas consumption is used to generate electricity. The lion’s share is consumed by the industrial, residential and commercial sectors, where its replacement is more difficult and has not progressed far. This is often ignored.

High energy prices and the uncompetitiveness of European industry may force a review of EU's energy policy later in the year, especially with regard to the exit from natural gas, if it is not to face the risk of deindustrialization.

Some European heavy industry companies have already started moving to places that offer cheaper energy, such as the US or the Middle East. This may accelerate in 2023.

With recession likely to affect many economies, and inflation and interest rates remaining high, high energy prices and the uncompetitiveness of European industry may force a review of EU's energy policy later in the year, especially with regard to the exit from natural gas, if it is not to face the risk of deindustrialization. As a result, the need for government interventions to reduce energy costs is likely to continue into 2023, despite the call by the ECB to phase these out.

After a difficult 2022, the European gas market appears to have entered into a new phase: a ‘new energy normal’. Gas prices are down from their peak, but Europe faces a long-term loss of competitiveness. Prices in mid-April were about three-times higher than pre-COVID and may rise to five-times by the end of the year. Surely this cannot be acceptable as the new energy normal.

The EU will have to secure gas at substantially lower prices than now, if the burden to EU households is to be reduced to affordable levels and industry’s competitiveness is to be restored – avoiding de-industrialization that is already happening. It will also have to be dependable and reliable and not vulnerable to fast-evolving global geopolitics.

Unless Europe realises this, it will sleep-walk into the next energy crisis later this decade, as the need for gas to make up for non-performing renewables becomes apparent. Without new production, gas supply will be tight, with gas and energy prices going up…again.

However, the extent to which this reduction in gas consumption will lead to permanent demand reduction remains unclear.

With no end in sight of the Russia-Ukraine war, global energy markets will continue to be unstable, making 2023 another difficult year for global energy. Last year’s energy challenges could be repeated next winter and probably the next. Europe is not out of the woods yet. As Simson said, Europe has come a long way, but it still has a tough job ahead of it.