Tanzania LNG gains critical momentum [Gas in Transition]

Tanzania’s Ministry of Energy and Minerals announced in March an agreement with Anglo-Dutch major Shell and Norway’s Equinor to develop a long-awaited LNG project in the south of the country. The ministry said negotiations had reached a successful conclusion and that a Host Government Agreement is now being drafted, alongside a production sharing contract covering the offshore acreage involved.

There is a long way to go before the project is actually developed, but it has never looked more likely to be built. A final investment decision (FID) is expected in 2025 with the front-end engineering and design (FEED) phase preceding FID. Construction time is likely to be five to six years, suggesting the large-scale project could come on-stream around 2030.

Plentiful feedstock

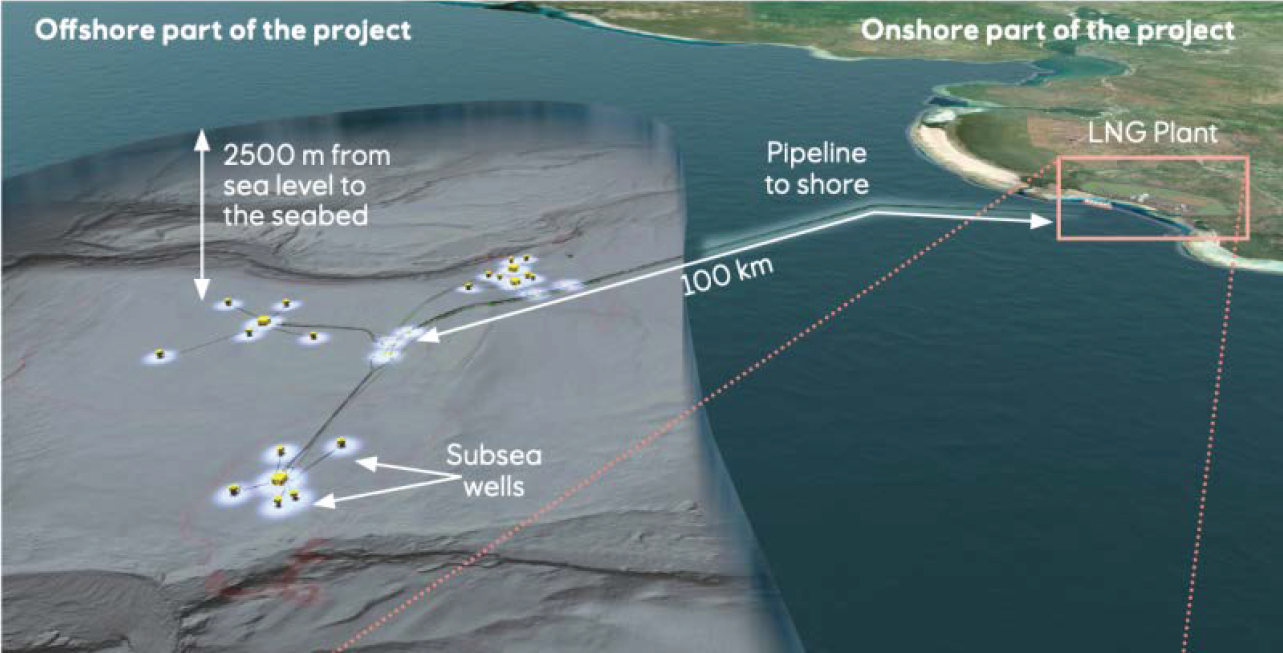

Blocks 1, 2 and 4 in the Mafia Deep Basin off the southeast coast of the country will provide feedstock for the plant. Equinor operates Block 2 with a 65% stake, alongside partner ExxonMobil, which holds the remaining 35% equity. Equinor estimates reserves on the block at more than 20 trillion ft3 (566bn m3).

Blocks 1 and 4 are operated by Shell with 60% equity, with Singapore’s Pavilion Energy and the UK’s Ophir Energy each holding 20% stakes. Ophir is now owned by Indonesia’s MedcoEnergi, while Pavilion is an offshoot of Temasek, a Singapore-based investment firm with interests in LNG shipping.

The Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) has the right to take a 10% stake in all projects once a FID has been made. The Shell consortium’s acreage contains an estimated 23 trillion ft3 (651bn m3), so the three blocks in total contain more than half of the country’s total proven gas reserves, which the government puts at 57.54 trillion ft3.

The Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) has the right to take a 10% stake in all projects once a FID has been made. The Shell consortium’s acreage contains an estimated 23 trillion ft3 (651bn m3), so the three blocks in total contain more than half of the country’s total proven gas reserves, which the government puts at 57.54 trillion ft3.

Much of the gas on the three blocks lies in water depths of up to 2,500m, with the gas lying another 2,500m below the seabed, pushing up development costs. The gas will be piped 100km onshore to a planned LNG plant near the small port of Lindi, about 70km from the Mozambican border.

The plant’s capacity has not yet been fixed, but figures of 10-15mn mt/yr in the first instance have been widely quoted and the reserves could certainly support this and more over a 20-25 year timeframe. A 2,000 hectare development area has already been secured by TPDC, with local residents relocated.

Further progress on the venture is likely to trigger more investment in offshore oil and gas exploration in the area, both on the existing blocks held by the two consortia and on adjacent acreage. Along the lines of the model adopted in neighbouring Mozambique, the LNG plant will be jointly owned, probably with each consortium owning their own dedicated trains. The strategy reduces permitting work and using shared infrastructure helps reduce costs.

Long time coming

The $30bn scheme had been repeatedly delayed, partly because of the hard line that former president John Magufuli took with foreign oil, gas and mining investors, passing legislation that retrospectively changed the terms of existing agreements. Equinor even wrote down the value of its Tanzanian assets by $982mn in early 2021 because the prospects of making progress on the project appeared so low.

However, two factors turned the situation around.

First, Magufuli died in March 2021 and was replaced by then vice-president Samia Suluhu Hassan. She has adopted a far more conciliatory attitude towards foreign investors in the natural resources sector and quickly reached out to the country’s gas investors upon assuming power. One of her first decisions was to replace Magufuli’s cousin, Medard Kalimani, as minister of energy and minerals, with the more pro-business January Makamba.

Second, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the resulting decision by European governments to phase out Russian gas imports re-ignited enthusiasm for a host of proposed LNG schemes, including in Tanzania. A framework agreement on the Tanzanian project was signed in June 2022 and the recent breakthrough reflects the view on the part of developers that much more LNG will be needed over the next 20-25 years.

The Lindi plant will lie just 90 km north of an even bigger planned LNG plant on the Afungi Peninsula in Mozambique. Work on the 12.8mn mt/yr project was indefinitely suspended in early 2021 as a result of militant attacks, but could resume this year. A total of 30.8mn tonnes/year is already planned for the Afungi site by consortia led by Total and ExxonMobil/Eni.

ExxonMobil in March invited companies to submit expressions of interest for a FEED contract for its project, also revealing a planned increase in capacity to 18 mn mt/yr.

As a result, coupled with Eni’s operational 3.4mn mt/yr Coral floating LNG project offshore Afungi, the cross-border area could host LNG production of 45-50mt mt around the turn of the next decade, with scope for significantly more. At the end of last year, Eni shipped the first liquefied gas from Coral, the first time ever that LNG had been produced in the eastern half of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Project challenges

There are considerable challenges to developing projects in the region as already shown by Total’s experience in Mozambique. Both the far south-east of Tanzania and the far north-east of Mozambique are among the least-developed regions in their respective countries, with very limited port, power and other infrastructure, plus poor road connections to the rest of the region.

However, both governments are keen to use LNG as a catalyst for regional development. In the case of the Tanzanian project, a new port will be required to handle LNG carriers as the existing Port of Lindi has a draft of just 3.8 m and is only suitable for handling small coastal vessels. Some of the gas produced will be ring-fenced for domestic use, including for a local power plant, while the government hopes that gas upplies will encourage wider industrial development in the region.

However, both governments are keen to use LNG as a catalyst for regional development. In the case of the Tanzanian project, a new port will be required to handle LNG carriers as the existing Port of Lindi has a draft of just 3.8 m and is only suitable for handling small coastal vessels. Some of the gas produced will be ring-fenced for domestic use, including for a local power plant, while the government hopes that gas upplies will encourage wider industrial development in the region.

Under Magufuli, more gas from the project was to be allocated for domestic use than LNG production, an additional factor weighing against an FID. This would be unusual for an LNG scheme, particularly given that there is no significant local demand as yet. Moreover, enthusiasm for building new gas-fired power plants in Tanzania will be tempered by the expected completion of the 2,115 MW Julius Nyerere hydro project next year, given that its output will exceed that of the country’s entire current installed generation capacity.

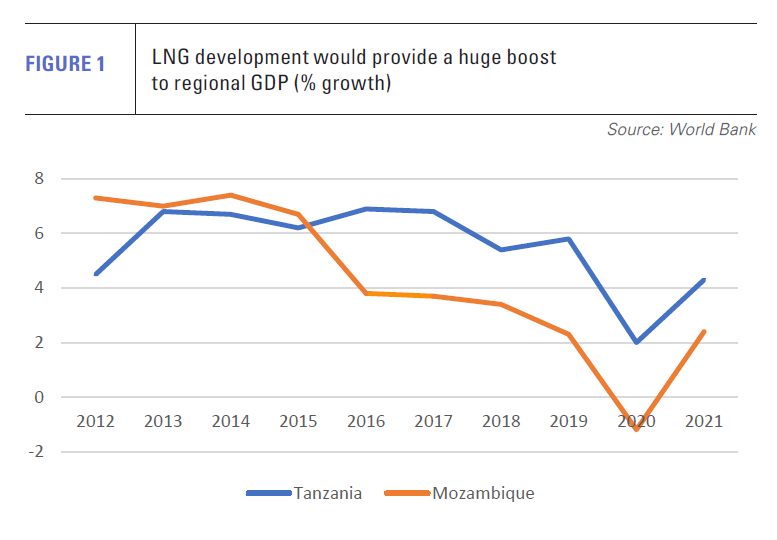

However, rapid demographic expansion and economic growth that has averaged 6% a year since 2005 could create substantial domestic demand, providing an outlet for natural gas produced on further discoveries in the area. Even then, however, Lindi lies far from Tanzania’s main population and industrial centres, so gas would probably have to be piped north to end users.

Steady as she goes

A big question is whether there will be any further delays before FID is taken, but the prospects look positive.

Even if an unexpectedly rapid resolution were reached regarding the war in Ukraine, the desire of European governments to diversify their sources of gas supply is unlikely to dissipate. Moreover, global LNG demand is growing by an average of 4% a year, and would almost certainly show stronger growth, if more short-term supply was available. As a result, the economic case for the Tanzanian LNG project is likely to remain strong.

On the other side of the equation, the Tanzanian government’s increased willingness to bring the project to fruition seems unlikely to change. Magufuli wrongly gambled that foreign investors would accept any terms because of the attractiveness of the country’s natural resources.

Hassan is unlikely to make the same mistake again and there is very little possibility of her position being challenged. The next presidential election is not until 2025 and the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) has not lost an election since independence in 1961, although the opposition is strengthening in the face of the CCM’s somewhat autocratic tendencies.

The $30bn LNG scheme would be the biggest single investment ever made in Tanzania and will provide a major boost to export revenues and government income. Excitement in the country over the project is growing and last year Stanbic Bank Tanzania described LNG as “the country’s very best economic opportunity.”

There are well-worn pitfalls in terms of the effect of oil and gas revenues on the stability of African economies, but hopefully Tanzania has learnt from the negative experiences of Nigeria, in terms of the dangers of over reliance on hydrocarbon income, and of Ghana, in relation to ramping up state expenditure too quickly.

Moreover, while this would be Tanzania’s first LNG project, the government already has two decades’ experience with gas development, as smaller fields further north already supply gas to several power plants, cement producers and other industrial consumers in and around the country’s economic capital Dar es Salaam. It should therefore possess the in-house skills to conclude the new agreements in a timely fashion.

It would be no surprise if the timetable for development were to slip, but it now seems more than likely that Tanzania will join the ranks of Africa’s LNG producers within the next decade.

Hydro to dominate Tanzanian electricity supply

Tanzania hosts nine gas-fired electricity plants with combined capacity of about 650 MW out of a total 1,732 MW of installed generating capacity, of which about 3 -MW is off-grid. Natural gas provides almost half of total electricity generated.

The country has 562 MW of hydro capacity, but this will jump with the expected completion of the behind-schedule 2,115-MW Julius Nyerere hydro dam in 2024. Other planned hydro schemes include the 360-MW Ruhudji and 2,100-MW Stieglers Gorge projects and the smaller 50-MW Malagarasi and 22-MW Rumakali plants.

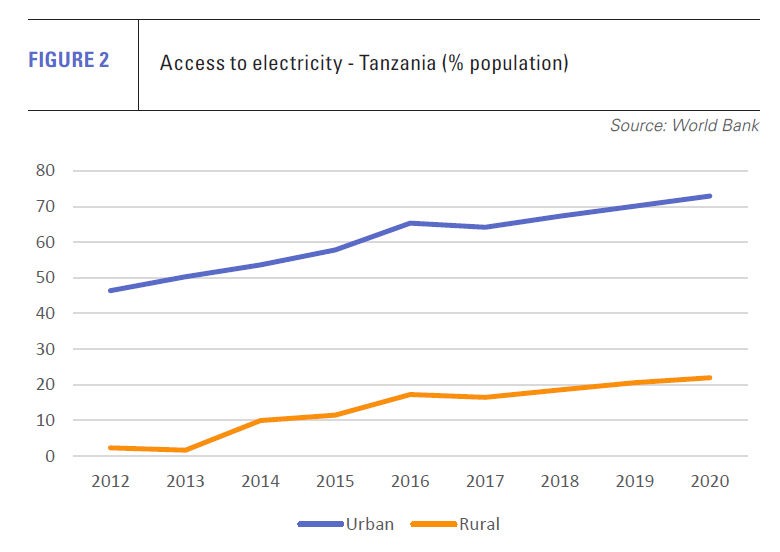

Tanzania has 6,139 km of transmission lines and 59 substations mainly owned and operated by the Tanzania Electricity Supply Company. In addition, the distribution network runs to about 149,000 km. Average annual electricity consumption per capita is 108 kWh, compared with a Sub-Saharan average of 550kWh.

About 40% of the population has access to electricity, but power demand is growing at an estimated rate of 10-15% a year. The government is targeting 10 GW of installed generating capacity by 2025. The country also imports small amounts of power from Uganda, Zambia and Kenya.