Algerian gas supplies form a key pillar of European energy security [Global Gas Perspectives]

Algeria has managed to defy forecasts that a combination of lacklustre production growth and rising domestic demand would squeeze export volumes. As a result, it has proved a reliable supplier of gas since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, both to Italy and Spain by pipeline, and to the EU more generally through LNG exports.

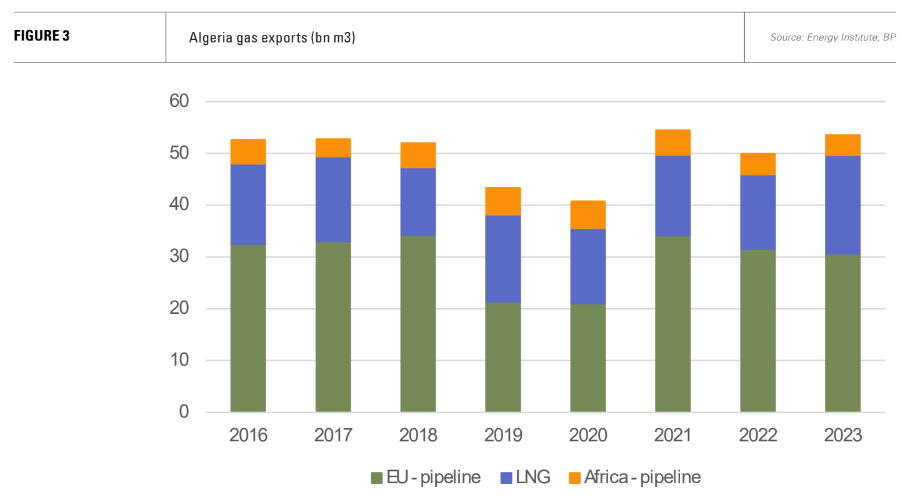

Algerian LNG exports reached 19bn m3 last year, still below export capacity, but 3.4bn m3 higher than in 2021 and the highest level in more than a decade.

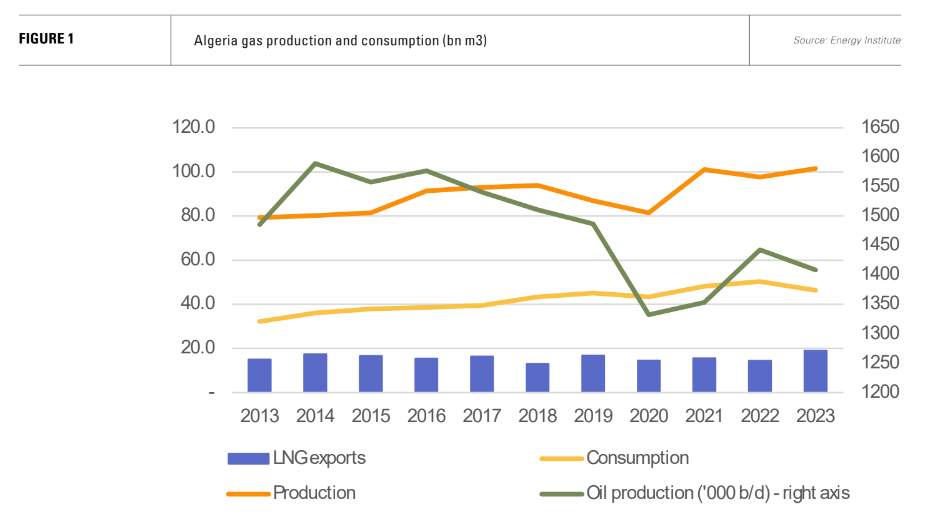

The resurgence in Algerian gas output was not, however, a response to the war in Ukraine. Production hit a record 101.1bn m3 in 2021, jumping almost 25% from 2020, according to Energy Institute data. It dipped in 2022 and then set another record of 101.5bn m3 in 2023. Exports followed suit and stood at 53.5bn m3 last year with a marked jump in LNG volumes of 4.6bn m3.

The increase in LNG exports last year was made possible by a combination of factors: lower pipeline exports, the return to record levels of production and a decline in domestic consumption. Algeria has excess export capacity for both pipeline and LNG, but exports of the latter are likely to take priority as European gas demand peaks and then declines as a result of the energy transition.

Gas dependence

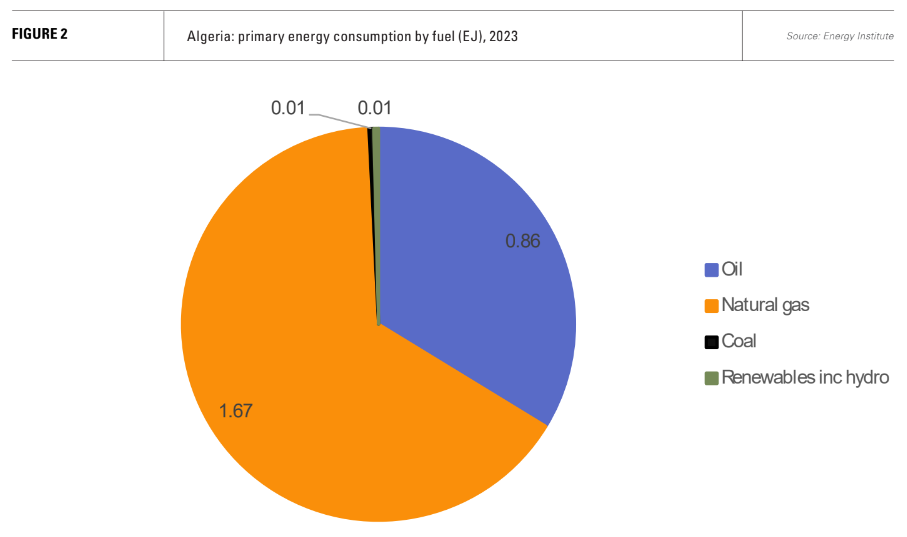

Algeria’s economy is heavily dependent on domestic gas, which accounts for 65.5% of primary energy consumption. The remainder is largely accounted for by oil, with less than 1% contributed by renewables including hydro. While the country lacks hydro potential, it has abundant sunshine and huge potential for wind, but has failed so far to exploit new renewable energy sources.

As a result, renewables have yet to make any inroad into an electricity system dominated by gas-fired generation. Rising domestic demand for the fuel has been a major factor limiting the country’s export volumes. In 2020, domestic gas production had fallen back to the level of 2015, but domestic demand was on a strong upward trajectory, rising from 32.1bn m3 in 2013 to 50.3bn m3 in 2022.

As such, the 4bn m3 drop in domestic gas consumption in 2023 was significantly off trend. It is unlikely to represent a long-term change in direction. Electricity generation fell from 91.2 TWh to 85.9 TWh, which meant lower gas demand for power generation. In addition, the country suffered droughts which subdued agricultural activity, which may have reduced demand for nitrate fertiliser, which requires natural gas as a key input for production.

Oil link boosts gas availability

In addition to the drop in domestic demand last year, another factor underpinning greater export gas availability is that Algeria has had to use less gas for reinjection into oil fields, owing to its commitment to production restraints as a member of OPEC.

A recent report by Wood Mackenzie shows reinjected gas volumes falling significantly from 2014 to 2022. “Prior to 2020, Algeria typically reinjected 30-40% of gross gas produced to support liquids production. Since 2020, reinjection rates have been around 25%,” the report says. This represents a gain of more than 20bn m3 of gas availability.

However, just as the trajectory of domestic gas demand remains uncertain, so too are the gas volumes required for future reinjection. Based on the unwinding of OPEC’s production cuts and the continued maturing of the country’s oil fields, Wood Mackenzie sees reinjection volumes increasing substantially from a low reached in 2022.

By next year, they will have exceeded the levels of 2014 albeit accompanied by higher levels of gross gas production. There is then a short plateau, according to the forecast. From 2029-30, reinjection volumes start to fall again, but gross gas volumes start to decline much more sharply, once again squeezing gas volumes available for export.

This forecast naturally carries uncertainties. OPEC’s unwinding of its production cuts is not going according to plan amid lacklustre demand for oil. In September, the organisation extended its cuts until the end of November. The reductions will be phased out over the course of next year – maybe.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s election success in the US heralds deregulation for the US oil and gas industry and potentially tax cuts which should support non-OPEC oil and gas production.

Further delays to OPEC’s unwinding and thus continued lower reinjection requirements in Algeria for oil production is thus a possible scenario. A focus on gas projects which also yield Natural Gas Liquids, which are not covered by OPEC’s quotas, will also allow Algeria to support liquids production without a larger drain on its gas volumes.

Alternatively, a scenario of high domestic gas demand growth accompanied by increasing reinjection requirements would bode ill for exports.

New production

Algeria has been more successful than many observers predicted both in bringing new gas into production and sustaining output from its giant but ageing Hassi R’Mel field, which still accounts for almost half of the country’s total gas output. Investment levels by foreign companies has been rising, reflecting the passage of a new hydrocarbons law in 2019 which improved the fiscal terms on offer and provided greater contract flexibility.

The government seems intent on sustaining investment in the oil and gas sector, earlier this year announcing that $50bn would be spent over the next four years to boost production. State oil and gas company Sonatrach promised $8.8bn this year alone.

In April, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed with France’s TotalEnergies for appraisal and development of gas resources in the northeastern Timimoun region. This was followed in May by an agreement with US major ExxonMobil to study development of hydrocarbon resources in the Ahnet and Gourara basins. An MoU with US major Chevron was signed in June to appraise areas of the Ahnet and Berkine basins.

Despite problems with tight reservoirs and high carbon dioxide content, long-standing projects have come into production, for example at Hassi Ba Hamou, Hassi Tidjerene and Tinerkouk. Other long delayed projects are still coming to fruition, for example Ain Tsila, which is expected to add 3.5bn m3 of gas in its first phase.

Nonetheless, observers retain their pessimism. Wood Mackenzie describes the country’s inventory of future greenfield gas projects as “thin”, reflecting the tough fiscal terms in force before 2019 and a consequent lack of exploration led by International Oil Companies. Opinion, in general, is that despite recent successes, sustaining Algeria’s recent gas boom will be hard.

Renewables on the horizon

According to a study by the International Finance Corporation and the Global Wind Energy Council, Algeria has the largest onshore wind potential in Africa at a huge 7,700 GW, but installed capacity at the end of 2023 was just 10 MW. Despite plenty of sunshine, installed solar capacity stood at only 452 MW.

Although there has been little progress to date, Algeria has set ambitious renewable energy targets. The government hopes to see 15-20 GW of renewable capacity installed by 2035, meeting 27% of electricity demand. If achieved this would free up substantial volumes of gas for export.

Two tenders in 2023 suggest the government is getting more serious about its renewable energy ambitions. In March, Sonelgaz-ENR, a subsidiary of the national gas and power company Sonelgaz, signed concession agreements with a variety of companies, including a number of Chinese firms, for the financing, construction and operation of 3 GW of solar power.

However, the investment environment for renewables in Algeria remains problematic. Grid limitations mean integration of renewable energy projects is expensive and often dependent on new transmission infrastructure. The country also subsidises electricity and Sonelgaz has a large financial deficit.

The Ukraine war increased EU interest in Algeria’s nascent energy transition, both on climate grounds and because the development of renewable power in the country would support gas exports and thus European energy security. The prospect of exporting hydrogen to the EU has been held up as a means of Algeria offsetting the eventual decline of European gas demand.

However, the EU-Algerian trade and investment relationship remains uneasy. In June, the European Commission started a dispute settlement procedure with Algeria under the 2002 EU-Algeria Association Agreement, following the failure of official complaints and direct negotiations. At issue are a number of trade restricting measures imposed by Algeria since 2021.

As a result, Algeria does not represent a particularly attractive or secure market for most foreign renewables companies to invest and domestic capacity in the sector is low. Chinese company involvement is likely to see an expansion of the country’s solar capacity and 15 GW by 2035 is by no means unrealistic, if the target is met predominantly by solar PV rather than wind.

However, unless renewables deployment accelerates, Algeria’s energy transition looks unlikely to put a significant dent in domestic gas demand this side of 2030.