Africa is missing the LNG boat [Gas in Transition]

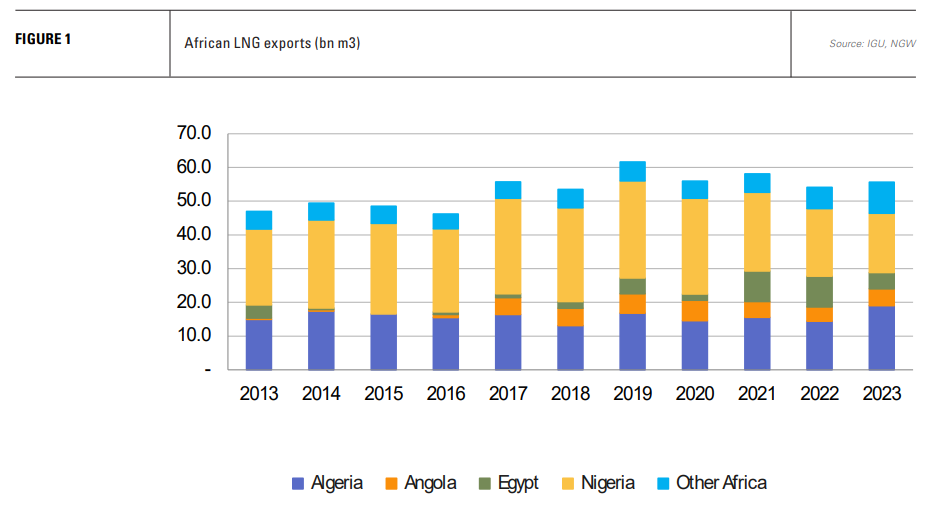

At 55.6bn m3, African LNG exports were lower in 2023 than the peak of 61.6bn m3 in 2019, just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (see figure 1). In 2022, African LNG producers, like others, reaped record high export prices as Russian pipeline gas exports to Europe fell and European LNG demand boomed, but the lack of planned expansion in this period represents a missed opportunity.

That opportunity was not to supply Europe with more LNG, but the chance to build capacity on the back of Europe’s gas crisis to position African LNG to meet future Asian demand. Both India and China, the two most populous countries in the world, have stated plans to increase the use of gas in their primary energy mixes and both lack sufficient domestic resources to do so without increased imports.

While European LNG demand has likely plateaued, it is the US and Qatar which will fulfil most of the additional demand from Asia, while Africa will miss out.

Reacting to the European gas crisis

At the onset of the Ukraine war, Europe launched a charm offensive in Africa in an attempt to shore up future gas supplies, but the gap between short-term need and the long gestation period required for LNG projects was never realistically going to be bridged.

Additions to LNG production capacity have come from projects already under construction. While Europe put in place new LNG import capacity with extraordinary rapidity, it is not so easy to expand gas supply and liquefaction capacity. And it is even harder to do so in countries with no former LNG experience, and which carry high levels of investment risk.

Investing in North America, or buying into a portion of Qatar’s expansion plans, was always going to be a more certain path to increased LNG production in the mid-2020s, and the scale of those opportunities has, to a large extent, crowded out more risky propositions.

Short-term response

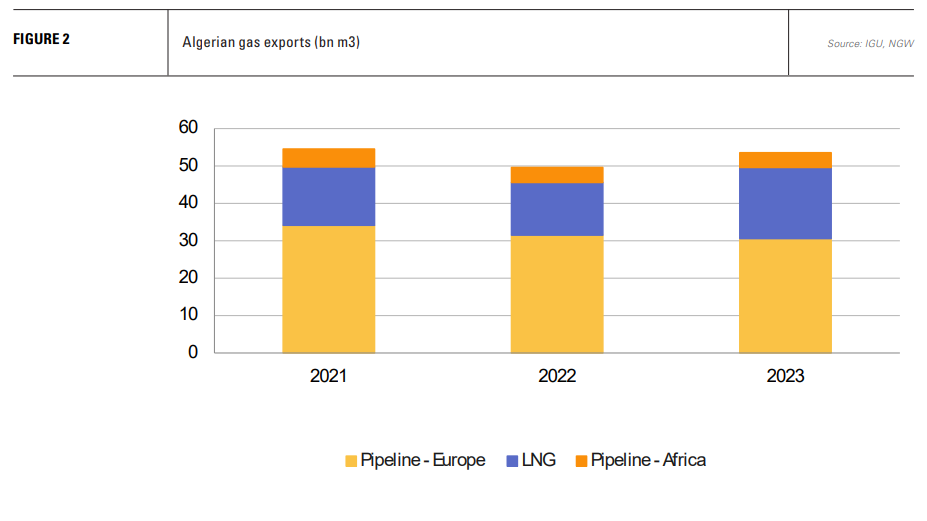

The short-term response had to come from existing producers. However, contending with strong demand growth amid limited upstream investment, Algerian gas exports were lower in 2023 and 2022 than in 2021 (see figure 2). While LNG exports jumped in 2023, they have come at the expense of lower pipeline exports to Europe and, to a lesser degree, to African customers.

Similarly, while Egypt managed to boost LNG exports in 2021 and 2022, increased domestic demand and declining output from the giant Zohr field saw them almost half in 2023. The country this year has returned to LNG imports via Jordan to meet domestic demand and maintain power supplies.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the performance of existing producers has been lacklustre. Angola LNG exported at a lower level each year in the period 2021-2023 than it did from 2017-2021. Nigerian LNG production has fallen each year since 2017, dropping from 28.8bn m3 to just 17.5bn m3 in 2023.

Nigeria LNG’s (NLNG) behind-schedule Train 7, which saw a final investment decision in 2019, was reported to be only 60% complete in February and start-up looks unlikely until 2026. Whether it will then work at full capacity, or take feedstock from the existing trains, is an open question, given that NLNG appears increasingly unable to source sufficient feedstock gas.

NLNG’s problem has long been not new capacity, but increasing the reliability of its feedstock supplies.

The green fields of East Africa

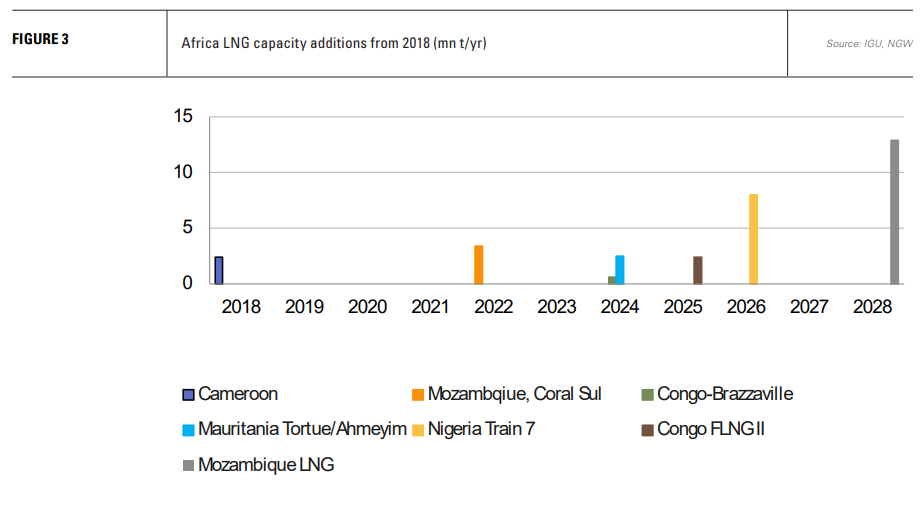

Large-scale greenfield projects have also fared poorly (see figure 3). Crisis in Europe did nothing to remove the challenges posed by LNG development in East Africa, and with Europe unable to guarantee long-term demand, East African LNG development is, in any case, more about Asia than Europe.

TotalEnergies said earlier in the year that it hoped to restart construction by mid-2024 on its $20bn Mozambique LNG project, which has been stalled since April 2021. It said that it had talked through contracts with suppliers and was re-engaging with financial institutions. US major ExxonMobil, meanwhile, has said it could take a decision on its now 18mn-t/yr Rovuma LNG project in Mozambique by the end of 2025.

However, a surge in militant attacks this year in the Cabo Delgado province, in which both projects are located, shows that the security situation remains volatile. Crisis24 reports that the militant threat remains elevated and that the first attack in over a year took place in neighbouring Nampula province in April, a worrying sign.

Meanwhile, Tanzania’s LNG prospects brightened considerably last year with the signing of an agreement between the government and project leaders Equinor and Shell in May. However, the government has since reported to have proposed changes, leading to delays in finalising the agreement and pushing back a final investment decision.

At an estimated $42bn, the Tanzania LNG project represents a massive investment. Its prospects improved when Samia Suluhu Hassan assumed the presidency on the death of president John Magufuli in March 2021. New presidential elections are due to take place by October next year. It remains uncertain how fair they will be and what support opposition parties may garner. Hassan has reversed some of the repressive policies of Magufuli.

However, the changes to the LNG investment agreement were made by deputy prime minister and energy minister Doto Biteko, a Magufuli ally, who Hassan recently brought back into the cabinet in an attempt to win back the support of Magufuli loyalists ahead of the election. With Biteko apparently revisiting Magufuli’s hardline resource nationalism, investors in Tanzania LNG may well decide to see how the electoral dust settles before moving ahead.

East Africa’s greenfield LNG developments increasingly look like creatures of the 2030s rather than the 2020s.

‘Other Africa’

LNG exports from newer producers rose from 5.1bn m3 in 2020 to 9.2bn m3 in 2023. However, this was primarily due to the start-up of Eni’s offshore FLNG Corul Sul project in Mozambique in 2022, the timing of which was fortuitous, but reflected an investment decision prior to the European gas crisis.

In Mauritania, Tortue/Ahmeyim LNG will start up this year, but again this project has been long in gestation. The Floating, Production, Storage and Offloading vessel, the 2.5mn t/yr FLNG Gimi, took three and a half years to complete, despite being a conversion from a 1976-built Moss-type LNG Carrier rather than a newbuild. It arrived on-site in January, but project operator BP in February put back the date of likely first gas until the fourth quarter of this year.

Meanwhile, ‘Fast LNG’, a term coined by US company New Fortress Energy (NFE), has not proved quite as fast or productive as had been hoped.

NFE has scaled back its Fast LNG plans considerably and proposed projects offshore Africa were the first to go. NFE had projects for Congo and offshore Mauritania on the planning board, but from a projected five new Fast LNG units expected to be operating from mid-2023 to 2025, only one is now expected to be in operation and it is located off Mexico’s Gulf coast.

Last year, NFE sold its share in the FLNG Hilli, which operates off Cameroon, and its current plans focus on Mexico and offshore Louisiana rather than offshore Africa.

The only clearly successful fast-track LNG project in Africa is Eni’s Tango FLNG, offshore Congo-Brazzaville. This came on stream in February 2024, just one year after the final investment decision was taken, but capacity is small – just 0.6mn t/yr. It could nonetheless be the harbinger of better things. According to Eni, a second FLNG facility is under construction with a capacity of 2.6mn t/yr, which is expected to come into operation as early as next year.

Subtract projects already under construction at the start of the war in Ukraine and the list of under construction LNG projects in Africa is minor. While there was never any hope beyond a few small-scale offshore FLNG projects of quickly monetising Africa’s unexploited gas resources, the sudden surge in European demand could have been leveraged to underpin investment in capacity that would ultimately target Asian markets.

The harsh reality is that most of Africa still has a high level of both operational and political risk. There are safer jurisdictions with ample gas reserves, in which the rules governing investment are more secure and likely to be respected.

Unless the projects are small, or very large, and therefore potentially worth the risk, Africa will struggle to compete with the Middle East or North America, where it is simply much easier to build LNG facilities because the surrounding infrastructure and supplier ecosystem is well developed and competitive.

Compare this to the greenfield projects of East Africa and it is clear that only the biggest and most experienced oil and gas companies are likely to take the plunge. Even then, they will not do so quickly, but very carefully, because of the huge investment sums at risk.