South African LNG plans still uncertain [Global Gas Perspectives]

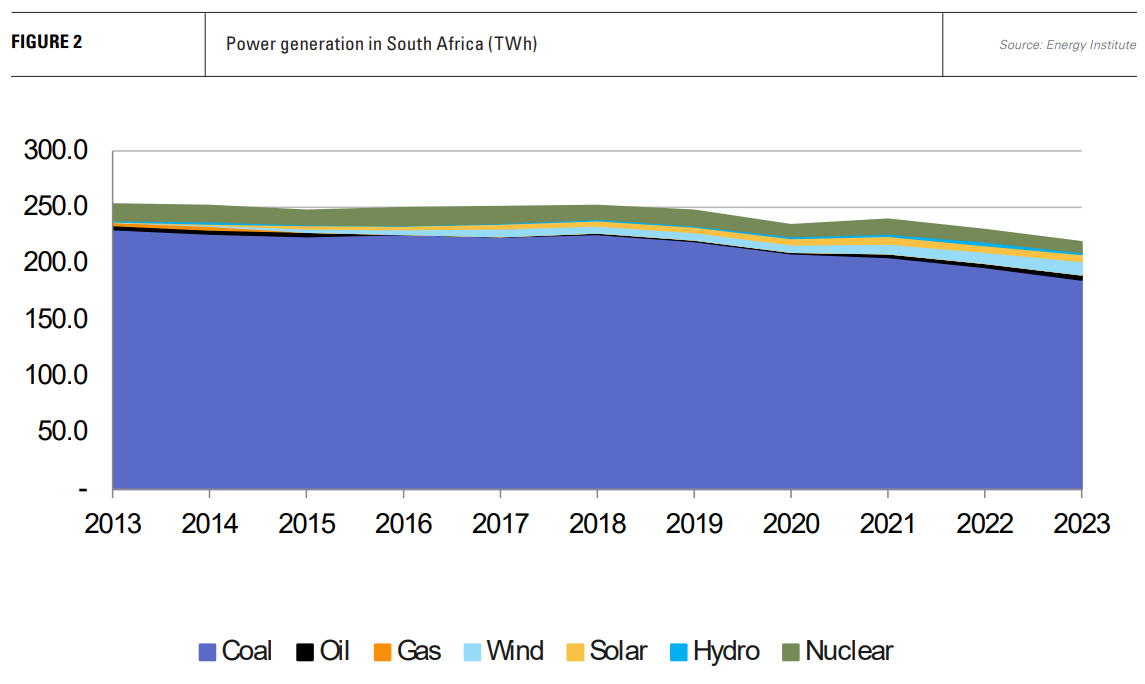

South Africa’s energy economy has long been dominated by coal, and the high emissions fuel remains by far the largest source of electricity generation in the country. Natural gas, in contrast, plays a minor role in the country’s energy mix, but still an essential one in supplying energy to South African industry.

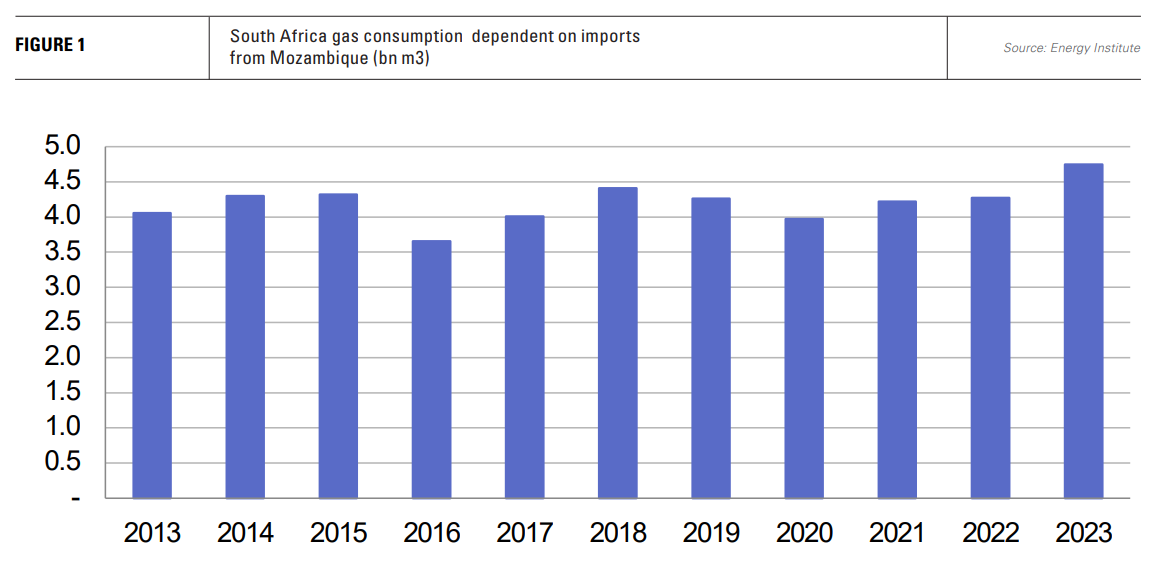

The supply of gas has fallen with the depletion of domestic fields, necessitating imports from Mozambique. South Africa imported the majority of its 4.7bn m3 of gas consumption in 2023 from its northerly neighbour. The lack of supply saw the fuel fall out of the power mix in 2014, and the shuttering of the country’s gas-to-liquids plant at Mossel Bay in 2020.

Imports from Mozambique are not sufficient to provide feedstock for the expansion of gas-powered electricity generation needed to bring an end to the country’s recurrent load shedding, nor to feed the planned conversion of capacity to gas required to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

To South Africa’s northwest, offshore oil and gas development is gathering momentum in Namibia, which could provide another source of imports, but not for some time. And, at home, there is the prospect of a rejuvenation in domestic supply, but this too faces major challenges.

As a result, LNG is sorely needed to fill the gaps in South Africa’s energy supply.

Mozambique gas

Mozambique has been supplying South Africa with gas from the onshore Pande, Temane and Inhassoro fields in Inhambane province since 2006. The gas flows through the 865 km ROMPCO pipeline to Secunda, the starting point of South Africa’s Sasol’s gas distribution network.

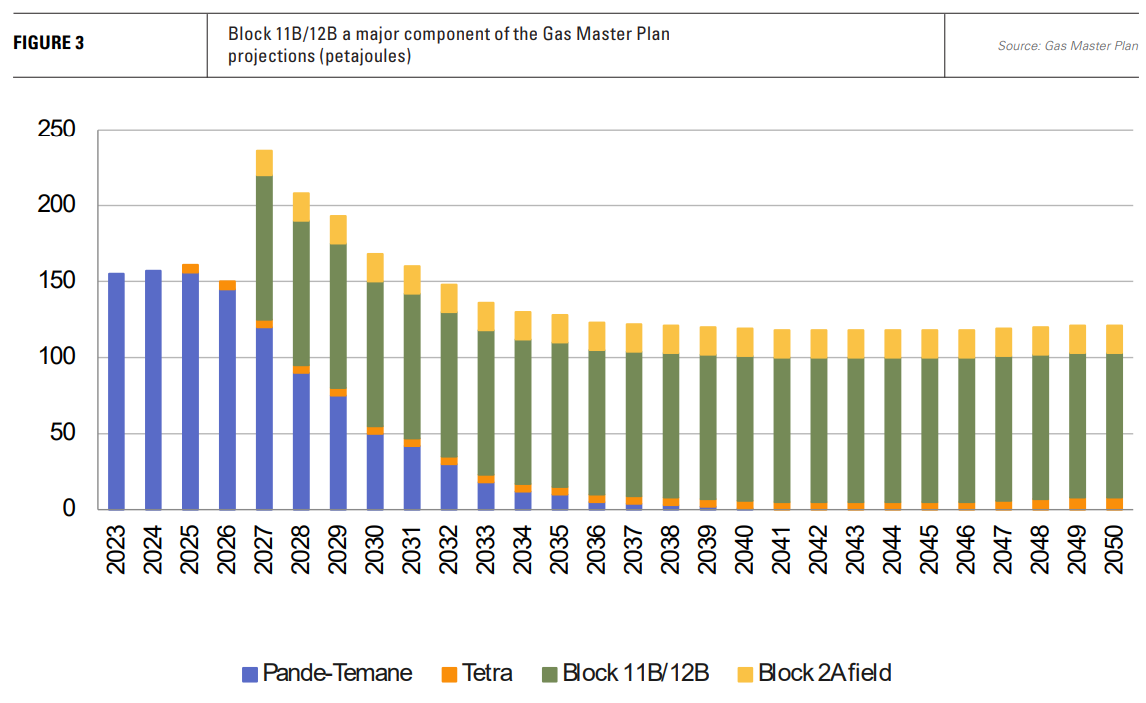

According to the government’s Gas Master Plan (GMP) published in April this year, production from the Pande-Temane complex will enter a steep decline from 2026. Sasol has said it will be unable to supply industrial customers in South Africa from June 2027, a one-year extension from an earlier warning that supplies would end in 2026. The remaining flows will feed Sasol’s facilities in Sasolburg and Secunda into the mid-2030s.

Sasol is nearing completion of its PSA project in Mozambique, which has helped sustain the supply of gas via the ROMPCO pipeline into 2027 and further investment may extend exports for longer. The Initial Gas Facility was completed in July last year. Sasol also made the Bonito-1 discovery in April last year on its onshore acreage, which is undergoing appraisal, suggesting potential to prolong Mozambique’s gas exports to South Africa.

State-owned PetroSA has also entered the scene, announcing a deal with Mozambique’s national energy company ENH, which would see 2 PJ/yr of gas (63.2mn m3/yr) supplied via the ROMPCO pipeline from the end of this year.

Although additional volumes from the Pande-Temane area could avoid the gas crunch feared by Sasol’s industrial customers, the company says they will at best provide a bridge until LNG imports begin.

Namibian oil dreams will come before gas

Namibia also offers potential as a relatively close source of imports. Volumes are likely to be larger than those offered by Mozambique, but they are unlikely to be available until 2030 or later.

Namibia’s offshore has become something of an oil exploration hotspot, following a number of major discoveries. Shell estimates that two wells in its PEL 39 area in the Orange Basin could hold 2.38bn and 2.5bn barrels of oil respectively. France’s TotalEnergies drilled the Venus exploration well in 2022, which it estimates could hold 5.1bn barrels of oil. First oil from the prospect is expected in 2029-2030.

More recently Portugal’s Galp carried out tests on two wells on its Mopane field, estimating the discovery’s potential at 10bn barrels or more. US oil major Chevron is expected to embark on an exploration campaign offshore Namibia later this year.

These are world class finds and, if developed, will also produce large quantities of natural gas with South Africa the closest major potential market. The Venus field, in particular, lies adjacent to the maritime boundary with South Africa and contains light oil and gas.

However, there is no guarantee the gas will make it to shore soon. Its most likely short-term use would be for reinjection and for power production offshore, while some will almost certainly be flared. Gas and LNG developments tend to lag oil development by years – a recent example being Guyana, where a consortium led by ExxonMobil started producing oil in 2019, but is only now considering its first natural gas production.

Any project to supply South Africa will also have to contend with the possibilities of LNG development, which would give the developers multiple markets rather than dependence on one. Either way gas development off the coast of Namibia is most likely a decade or more away as developers focus first on producing oil.

Domestic gas setbacks

South Africa has a small number of producing gas fields, but none are particularly large. The two largest, Ikhwezi and E M Gas, produced only 382mn m3/yr and 310mn m3/yr respectively in 2023. A number of new gas fields promise to increase South Africa’s domestic natural gas supply, but they are not progressing smoothly.

The Brulpadda-Luiperd discoveries hold an estimated 90bn m3 of gas. However, TotalEnergies, which made the discoveries in 2019 and 2020, announced its withdrawal from Blocks 11B/12B in July, on the basis that their development was not economically viable. Partner Canadian Natural Resources had already left the project and QatarEnergy had also pulled out. TotalEnergies also relinquished its exploration licence covering blocks 5/6/7, but retained its Orange Basin blocks in South African waters close to Namibia.

It may be that the fields are not economically viable enough – the international partners had better prospects, and ones not limited to the South African market. As a result, a new developer may emerge, but the exit of TotalEnergies at minimum means delays for the field’s development.

Other fields currently reported to be in the front-end engineering and design phase include the E-BK field, which is being developed by PetroSA, and the Ibhubesi gas field, which is operated by South African explorer Sunbird Energy.

However, according to the GMP, none of these fields make the major contribution to gas supply that was expected from Brulpadda-Luiperd. The only relatively minor supply additions foreseen by the GMP come from Block 2A (Ibhubesi) from 2027 and the onshore Tetra gas project in the Free State from 2025.

According to the GMP projections, even with Brulpadda-Luiperd coming onstream in 2027, gas supply in 2030 would be lower than in 2023.

Need for gas clear

The country certainly needs gas. The government says that 6 GW of new gas-fired generating capacity is required to end the load shedding currently plaguing the country. It is prioritising the development of a 1 GW plant near Coega in the Eastern Cape and a 2 GW mobile facility. The government also expects about 5.5 GW of new renewable energy capacity to come online by 2026.

However, these represent short-term measures designed to address current power shortages rather than meeting the twin demands of growing electricity consumption and the phasing out of the country’s polluting coal-fired power plants.

Power demand is expected to jump by around 40% by 2030 to 300 TWh, according to consultants Rystad Energy, which does not see the expansion of renewable energy keeping pace. Energy demand is being driven by population growth, urbanisation and industrial demand.

As a result, LNG offers a supply option which could fill the gap. In January, a consortium led by Dutch company Vopak was selected as the preferred bidder to develop an LNG terminal at Richards Bay, South Africa’s largest coal export point. The facility is expected to be operational in 2027 with initial capacity of 2mn tons/yr, rising to 5mn t/yr, according to partner the Transnet National Ports Authority.

LNG import plans are also afoot for the Ngqura and Saldanha Bay deepwater ports, while four other locations are being considered for small and medium-size LNG facilities. The Gas Master Plan envisages just over 500 PJ of LNG (15.6bn m3/yr, 11.4mn t/yr) imported in 2029 from four Floating Storage and Regasification Units located at Richards Bay, Ngqura and Saldanha Bay.

Another option is a planned LNG import terminal at Matola in Mozambique, which would supply gas to the ROMPCO pipeline and allow electricity generated from the gas in Mozambique to be exported to South Africa. However, TotalEnergies, which had promised a final investment decision on the project by this September, has yet to make an announcement.

In all, South Africa’s gas supply plans have a high degree of uncertainty. Neither the Richards Bay nor the Matola LNG projects can be certain of coming onstream in time to meet anticipated gas shortages in 2027. The case for LNG is strong, but the internal market for gas and its regulation do not appear to inspire confidence in investors. LNG in South Africa may prove a case of too little too late, leaving the country to struggle on with its creaking and polluting coal-fired power plants.