TurkStream: Geopolitical Impact and Future Prospects

The leaders of Bulgaria and Serbia, Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and President Aleksandar Vucic, took part in the ceremony as well. TurkStream is a landmark achievement. First, it strengthens economic links between Russia and Turkey, at a time when they have found themselves at odds in Libya and northwest Syria. Indeed, the pipeline across the Black Sea had many hoops to surpass to make it to this point, since it was proposed in December 2014 by Putin. TurkStream was put on hold during the crisis in Russian-Turkish relations caused by the shoot-down of a Russian jet in November 2015 and was subsequently resumed once ties were normalized in August 2016. Second, TurkStream adds to Moscow’s geopolitical clout as it establishes yet another export route bypassing Ukraine. Since the start of 2020, gas volumes shipped through Russia’s southwestern neighbor have dropped by a staggering 40%. Last but not the least, the new pipeline brings Turkey a step closer to fulfilling its long-standing ambition to turn from a major consumer of gas to a transit country and, potentially, an intermediary in Eurasian energy trade.

This report examines TurkStream’s political and economic impact on Turkey and its neighbors in Southeast Europe. It argues that the pipeline’s extension into the Balkans and Central Europe will face further delay. Meanwhile, Russia will lose its market share in Turkey as well as in Greece and Bulgaria along with some Western Balkan countries. Efforts at diversifying gas sources, improving interconnectivity at the regional level and upgrading infrastructure are already changing the rules of the game, even though the economic downturn in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic is sure to slow down cross-border projects.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

What is TurkStream?

TurkStream is an iteration of South Stream, a project Russia had advanced from the mid-2000s until 2014. In partnership with major European firms, such as Italy’s ENI and Electricité de France, Gazprom aimed to construct a pipeline running from the Black Sea port of Anapa in the Russian Federation all the way to Varna in Bulgaria. From there, South Stream would reach overland to Austria, crossing Bulgaria, Serbia and Hungary. Russia ended up calling off the project because of a protracted dispute with the European Commission over the applicable rules. Brussels insisted that Gazprom could not hold a large stake and exclude competitors from using the pipeline. The downturn in Russia-EU relations after the seizure of Crimea in March 2014 killed efforts to find a compromise formula. Putin blamed Bulgaria for walking out from the South Stream initiative under Western pressure.

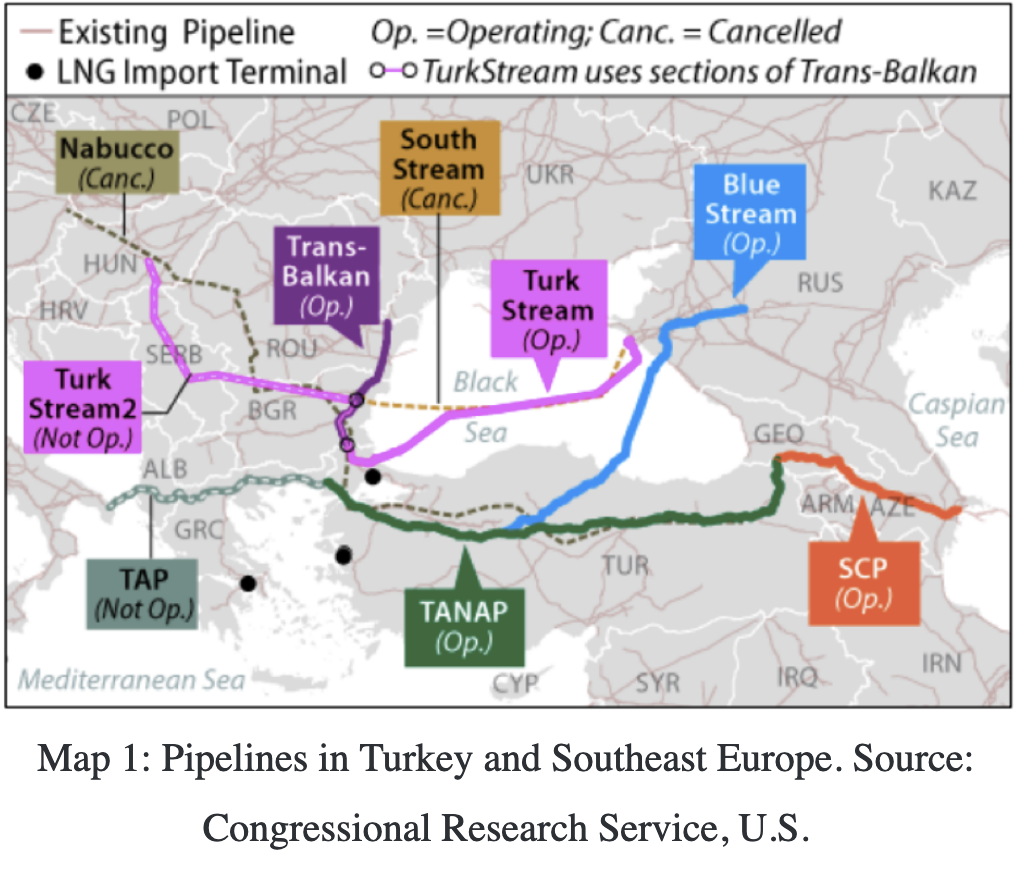

With South Stream effectively frozen, Russia turned to Turkey as an alternative. The result, TurkStream, is a watered-down version of its predecessor. It has an annual throughput of 31.5 billion cubic meters (bcm), half of South Stream’s projected capacity. Running from Anapa to Kiyikoy (Midye) in the Kirklareli province of northwestern Turkey, TurkStream has two parallel strings. String 1 is designed to pipe up to 15.75 bcm a year for the Turkish market. In practice, it redirects the deliveries Turkey has been receiving since 1988 through the so-called Western route, that is the Trans-Balkan Pipeline crossing Ukraine, Moldova, Romania and Bulgaria (See Map 1). The second string is bound for the Balkans and Central Europe.

The pipeline is currently operational all the way to Malkoclar at the Turkish-Bulgarian border. On 1 January 2020, Gazprom reported the start of physical deliveries, on average about 1 bcm a month. In January, more than half went to the state-owned BOTAS and several private companies importing Russian gas to Turkey. The rest was absorbed by Bulgaria, Greece and North Macedonia. Shipments to Serbia and Hungary are not possible as the Bulgarian and Serbian grid are yet to be connected. TurkStream therefore remains underused. Even String 1 serving Istanbul and the Marmara region is not working at full capacity. As discussed later in the paper, gas demand in Turkey is contracting – and perhaps likely to fall even further. This also brings down volumes shipped through Blue Stream, the first Black Sea pipeline Russia completed in 2005, to Ankara and central Anatolia.

TurkStream gives Russia and Turkey some advantages: Gazprom has attained its objective to directly access the Turkish market, without having to deal with countries lying in between. Turkey, for its part, has the physical ability to receive and transmit Russian gas to the EU which, at least in theory, provides it with leverage vis-à-vis both Europe and Russia.

Balkan Stream at a glance

Borisov and Vucic’s presence in Istanbul on January 8th was anything but unexpected. Bulgaria and Serbia are crucial for the second phase of TurkStream (also known as the Balkan Stream), from the Turkish-Bulgarian border to the Baumgarten gas hub, not far from the Austrian capital Vienna. TurkStream 2/Balkan Stream is designed to reach Central Europe where demand has traditionally been strong. The pipeline will likewise lock in the Russian firm’s dominance in much of Southeast Europe. That includes Serbia and Bulgaria, where Gazprom enjoys a virtual monopoly as a supplier. Still, Belgrade and Sofia consider Russian projects as vehicles to generate jobs and investment into the local economies. The prevailing narrative about the defunct South Stream, for instance, was that large European states as well as the US forced its cancellation. The Balkans suffered as a result, losing potential revenue from transit fees along with other economic benefits. By contrast, Russian projects in Western Europe, such as the Nordstream pipeline, had moved forward, according to this line of analysis. Turk/Balkan Stream has therefore been welcomed, particularly by pro-Kremlin commentators, as an opportunity to obtain partial redress and as an opportunity to reset ties with Russia.

Balkan Stream has run into obstacles from the outset. The Bulgarian grid operator Bulgartransgaz signed a construction contract as late as September 2019. A lengthy legal battle with Arkad Engineering, a Saudi-led consortium that originally won the tender worth EUR 1.1 billion, held up the work. At a meeting with the Serbian President Vucic in Sochi (4 December), Putin blamed the Bulgarian side for deliberately delaying the project. During the launch ceremony in Istanbul (January 8 2020), Borisov assured Russia’s leader that the 474 km-long stretch would be up and running in June. However, the COVID-19 crisis has pushed the target date further back in time. In a telephone call with Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Bulgarian Foreign Minister Ekaterina Zaharieva put forward the end of 2020 as a deadline. Meanwhile, authorities in Belgrade confirm that construction work in Serbia has been completed and Russian gas can now be delivered to the Hungarian border once Bulgaria finishes the section of the pipeline in its territory.

There is a key difference between the two countries when it comes to Balkan Stream. In Serbia, the pipeline is owned by a joint venture where Gazprom controls 51% of the shares and the state-owned utility Srbijagas 49%. Such an arrangement would not work in Bulgaria due to the EU antitrust legislation. The Bulgarian stretch is therefore under the ownership of the grid operator Bulgartransgaz. To comply with EU rules, Gazprom has to bid to book capacity against competing firms. That is why the Bulgarian government maintains that the Balkan Stream is compatible with the Union’s policy to promote energy security through the diversification of supplies. The pipeline could be used for transporting gas from other sources – e.g. Azerbaijan, liquefied natural gas (LNG) coming from Greece or Turkey, Iran, Iraq or other Middle Eastern producers etc. Prime Minister Borisov has been advocating plans for setting up a trading hub in Bulgaria and soliciting funding from the European Commission. However, this is a long shot. At present, the Balkan Stream is almost exclusively benefitting Gazprom as no other large gas seller is interested in booking capacity. The financial risk in the meantime is borne by Bulgartransgaz which has raised EUR 200 million for the contract with Arkad.

Changing Gas Markets

Though TurkStream is a coup for Russia’s energy diplomacy, its economic impact is far less certain. The gas market in Turkey and its Southeast European neighborhood is becoming growingly competitive and Gazprom’s share is indeed contracting. In 2018, Russia imported 23.6 bcm of gas from Russia, 7.9 bcm from Iran and 7.5 bcm from Azerbaijan. LNG accounted for the remaining 22.5%. In 2019, however, imports from Russia declined by more than a third to 15.51 bcm. The same trend is observable in Southeast Europe. Over the first half of the year, Greece imported a quarter less from Russia compared to the same period in 2018. [10] Overall, Gazprom’s deliveries to Turkey and its neighbors went down from 19.5 to 14.2 bcm, a 27% decrease.

There are multiple reasons why Russia is losing its grip on local markets. Firstly, demand in Turkey, the region’s largest market, is shrinking as the economy is faltering. In 2019, overall imports went down from 50.3 bcm to 45.2 bcm. The downward trend is likely to continue in 2020. Since March when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Turkey and its neighbors, consumption appears to be in sharp decline. Turkey’s Electricity Producers’ Association, for instance, reported a drop of 20% in the output of electricity at power plants running on natural gas in April.

Secondly, cheap Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is proving to be a game-changer. LNG imports jumped from 22% of the total volume in 2018 to 28.3% in 2019. To put it in a longer-term perspective, purchases expanded from 6.1 to 12.7 bcm between 2013 and 2019. BOTAS, a Turkish state-owned oil and gas trading corporation, is turning to LNG because of the low prices. It has long-term supply contracts with Algeria’s Sonatrach, with Qatargas and with NLNG (Nigeria) but has also been buying on the spot market, including from U.S. companies.

Turkey has also invested in LNG import capacity. Two floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) became operational in recent years. One at Aliaga in Izmir (December 2016) and the other off Dortyol in the Hatay Province. A third FSRU is planned for the Saros Gulf in the Aegean (Turkish Thrace). Moreover, Turkey is expanding its gas storage capacity with the aim of reaching 20% of its annual consumption. Put simply, BOTAS could buy gas when prices are low to match demand from households, electricity producers and industries during peak periods – e.g. the winter months. That means that Gazprom is set to lose its market share in Turkey, its second most important market after Germany.

LNG is gaining ground in other countries too. In the last quarter of 2019, LNG imports to Greece expanded three-fold compared to the same period in 2018 and reached 1.2 bcm. Over the entire year, the Hellenic Republic purchased 2.8 bcm of LNG vs 2.4 bcm from Gazprom. As of 2019, the Greek state-owned gas utility DEPA has been selling LNG to Bulgarigaz. Greece and Bulgaria are furthermore cooperating on a project for a FSRU off the port of Alexandroupolis in the northeast part of the country. In January, Bulgartransgaz confirmed its intent to buy a 20% stake in Gastrade, the company behind the venture. DEPA has another 20%, with the rest controlled by Copelouzos. Companies from the US, Israel, Qatar and Algeria have all shown interest in the project. [19] With an annual capacity of 5.5 bcm, the FSRU at Alexandroupolis could serve the wider regional market thanks to the Greece-Bulgaria interconnector (IGB) which is now under construction. Both projects enjoy political support from the US and were discussed during the White House meetings Donald Trump held with Prime Minister Borisov (25 November 2019) and Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis (7 January 2020).

Third, Azerbaijan is emerging as a rival supplier to Gazprom on the markets in Turkey and in Southeast Europe. In December 2019, the Trans-anatolian Pipeline’s (TANAP) last stretch was inaugurated. The pipeline, which has been serving the Turkish market since mid-2018, has now reached the border with Greece. TANAP brings in 16 bcm from the Shah Deniz offshore field in the Caspian Sea. Of those, 6 bcm go to Turkey (around a fifth of its imports), with the other 10 bcm destined for Southeast Europe and eventually Italy. At the Greek border, TANAP connects to the Transadriatic Pipeline (TAP) which crosses Greece and Albania and ends in the Melendugno Terminal in the southern Italian province of Apulia. Once TAP starts running, Caspian gas will make it to Southeast Europe too, making the much discussed Southern Gas Corridor a reality. Both Greece’s DEPA and Bulgargaz have contracts with the Shah Deniz consortium, which backs TANAP/TAP, for 1 bcm a year. This corresponds to about one-third of annual consumption in Bulgaria and just under one-quarter in Greece. Caspian gas will also reach Albania and, in the event that interconnectors are built, the rest of the Western Balkans.

Azerbaijan already sells large volumes on the Turkish market. In January-March 2020, for instance, Turkey imported some 3.57 bcm as compared to 2.6 bcm in the first quarter of 2019. Ankara sees these deliveries as important for a number of reasons. Energy links reinforce the alliance between Ankara and Baku, a priority for all Turkish governments since the early 1990s. But also BOTAS’s contract with the Shah Deniz consortium contains no destination clause, in contrast to those signed with Gazprom. In other words, Turkey can legally resale the gas it buys from Azerbaijan to other customers. That is beneficial in light of its long-standing objective to become a gas trading hub and thus capitalize on its geographic position in between hydrocarbon producers and energy importing countries.

The Southern Gas Corridor also drives forward regional cooperation. In contrast to the Eastern Mediterranean, where gas has become a bone of contention, in Southeast Europe it advances market integration between Turkey and neighbors such as Greece and Bulgaria. The Balkan Stream and the Trans-Balkan Pipeline could also be reversed to pump gas export from the south to the north, which would certainly benefit Turkish companies.

Future Prospects

Russia’s strategic interest is to retain Turkey as a market and leverage energy ties in order to enhance its clout in regional and international politics. Turkey, by contrast, would like to expand its room for maneuver and reduce its dependence on external suppliers. The same applies to its Balkan neighbors, though Serbia has clearly lagged behind others in terms of the diversification of supplies. Taken together, LNG and the Southern Gas Corridor provide a hedge against Russia which has made some headway thanks to TurkStream.

The moment of truth will come with the renegotiation of the long-term supply contracts Gazprom has signed with Turkey in the next five years. Deals worth 8 bcm signed with BOTAS and four private companies currently using TurkStream are expiring at the end of 2021. Another large batch of contracts covering close to 80% of imports will lapse by 2026. That includes agreements with Azerbaijan, Iran and LNG suppliers. Turkey will be driving a hard bargain and ask the Russians as well as its other partners to offer better terms. That involves both lower prices (through a new pricing formula) and, likely more importantly, waiving the take-or-pay clause which obliges BOTAS to either pipe in a certain number of volumes each year from the respective supplier or financially compensate it accordingly. Low LNG prices on the spot market will no doubt be a tool in the forthcoming negotiations with Gazprom and, subsequently, with other firms.

In the short term, TurkStream will remain underused. Turkey is not in a position to utilize the full capacity of the pipeline’s first string because of the looming recession and the cheaper alternatives. The second string (Balkan Stream) has fallen behind schedule. Once it is completed it is bound to cause political controversy. The section in Serbia already attracted criticism from the Energy Community, a Brussels-backed body tasked with extending the EU legislation to countries wishing to become members. The dispute can heat up if the US steps into the fray, as it has done in the case of the Nordstream 2 pipeline. But even if the Balkan Stream comes online it is unlikely to work at full capacity at the onset. As in the Turkish case, sluggish demand in downstream countries of Southeast and Central Europe along with competition from other suppliers could spell the victory of economics over crude geopolitics.

Dimitar Bechev

Dr. Dimitar Bechev is Senior Associate Fellow at Al Sharq Forum focused on Russian foreign policy towards the Middle East and North Africa region. He is a Visiting Scholar at the Center for European Studies, Harvard University, and is also the director of the European Policy Institute, a think-tanked institute based in Sofia. Former positions filled by Dimitar include Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.