The Pure Hydrogen Gas Turbine is Coming [Gas Transitions]

Hydrogen is hot (again). A new report from the International Energy Agency (IEA), The Future of Hydrogen: Seizing Today’s Opportunities, released on June 14, is just the latest in a long series of reports, roadmaps and announcements from industry, researchers and policymakers, all stressing the “vast potential of hydrogen to become a critical part of a more sustainable and secure energy future,” as the IEA put it in its press release. (For an overview of some of the most recent developments in hydrogen, see my Gas Transitions article here.) With the Olympic Games in Tokyo in 2020 gearing up to be the Hydrogen Olympics, the hype will only get hotter in the coming years.

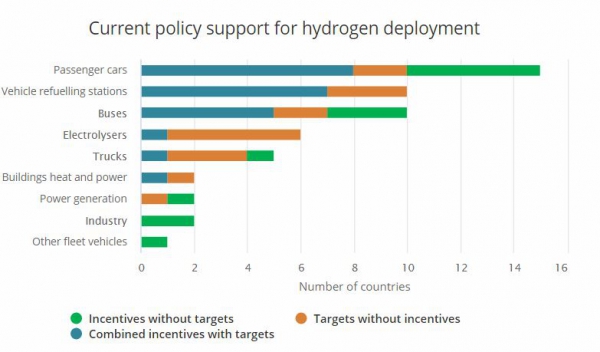

So far most of the hydrogen projects and studies that have been undertaken focus on the possibilities of hydrogen in transport and, increasingly (as Jorge Chatzimarkakis, head of industry association Hydrogen Europe notes), also in industry. Much less attention is being paid to the potential of hydrogen in power generation. As the IEA report notes, so far little policy support has been given to promoting hydrogen in power generation, the only exceptions being Japan (which has a target of 1 GW of hydrogen-based power production in 2030) and South Korea:

Source: IEA, The Future of Hydrogen: Seizing Today’s Opportunities

However, this could change in the coming years, as all major gas turbine manufacturers are working on building turbines fit for hydrogen, and, perhaps even more significantly, on technologies to retrofit existing gas turbines to be used with hydrogen.

Low load factors

At this moment, hydrogen still plays a negligible role in the power sector. According to the IEA report, it accounts for less than 2% of electricity generation. “Although pure hydrogen does not generally feature as a fuel in power generation today,” notes the report, “there are small-scale exceptions. For example, a 12-MW hydrogen-fired combined-cycle gas turbine in Italy uses hydrogen from a nearby petrochemical complex, while in Kobe, Japan, a hydrogen-fired gas turbine is providing heat (2.8 MW) and electricity (1.1 MW) to a local community. Somewhat more common is the use of hydrogen-rich gases from steel mills, petrochemical plants and refineries.”

According to the IEA, “reciprocating gas engines can already handle gases with a hydrogen content of up to 70% (on a volumetric basis), while in the future gas engines should be able to operate on even 100% hydrogen.” Fuel cells are another option for the future. The IEA notes that “global installed stationary fuel cell capacity has been rapidly growing over the last ten years, reaching almost 1.6 GW in 2018,” from almost zero in 2007, although only around 70 MW uses hydrogen as fuel, the rest running mostly on natural gas.

There also some – relatively small – gas turbines that are already running partly on hydrogen. Most existing gas turbine designs, notes the IEA, “can handle a hydrogen share of 3-5% and some can handle shares of 30% or higher.” In Korea, “a 40-MW gas turbine at a refinery has run on gases with a hydrogen content of up to 95% for 20 years.” Both in Japan and in the Netherlands (see box), projects are underway to convert gas turbines to use pure hydrogen. The IEA report sees a “potential” for hydrogen in power generation, although it does not specify what that potential could be.

Hydrogen could become an attractive flexible generation option, supporting the integration of solar PV and wind into the electricity system, says Uwe Remme, energy analyst at the IEA. Fuel cells remain relatively efficient at low load factors. Hydrogen-fired CCGTs benefit from lower capital costs per unit of power compared with other low-carbon flexible generation options, such as biogas power plants and plants that are based on carbon capture, use and storage, says Remme. That capital cost advantage becomes more pronounced when the load factor is low, compensating the often higher fuel costs of hydrogen compared with natural gas.

For Remme, the use of hydrogen in power generation should not be seen as competing with hydrogen uses in the chemical industry or refineries, but rather as complementary. “At the IEA we see great potential for hydrogen in industrial clusters, for instance existing uses of hydrogen in ammonia plants and refineries around ports. There new uses of hydrogen, including power generation and storage, could benefit from the concentration of hydrogen demand, reducing infrastructure costs.”

Remme has no doubt that, if the demand is there, turbine manufacturers will be able to deliver turbines that can use hydrogen at “moderate” additional costs. “The manufacturers tell us that the technology is already there, at least for smaller turbine designs.”

Pure hydrogen

EUTurbines, the European association of turbine manufacturers, goes one step further: it has given out a pledge that if customers ask for gas turbines that can operate with 100% hydrogen, they will get them, by 2030. In January of this year, the members of EUTurbines (Ansaldo Energia, Doosan Skoda Power, GE Power, MAN Energy Solutions, Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Siemens and Solar Turbines) officially committed themselves to “meeting customer demand for gas turbines operating with 100% hydrogen” by 2030.

In addition, as intermediate steps, EUTurbines made commitments for 2020 to:

- “deliver in Europe only gas turbines that are capable of running with renewable gas;”

- “provide customers with gas turbines that can handle a share of 20% hydrogen;” and

- “provide retrofit solutions for existing power plants to make them fit for renewable gases.”

Ralf Wezel, secretary-general of EUTurbines, explains the reason behind this move: “The manufacturers for a long time saw themselves as suppliers of gas turbines that would serve mainly as backup dispatchable generation. When they realised that EU climate ambitions imply that natural gas is only a transition fuel in Europe, they understood they had to be ready for carbon-neutral fuels to be future-proof.”

Wezel says the manufacturers have now repositioned themselves as “fuel-neutral” suppliers. “We deliver a technology that uses certain physical principles, but we are not bound to a certain fuel. We guarantee our customers that they will be able to handle renewable gases, such as hydrogen and biogas, so they need not be concerned about the future.”

According to Wezel, although there are gas turbines in operation that can handle high proportions of hydrogen, these are usually small turbines. “One technical challenge is that hydrogen burns at different temperatures. When you burn hydrogen, you get higher NOx emissions, which could in some cases exceed legal limits. One solution for this is injecting water in the combustion chamber, which brings down the temperature. But with large turbines you have to use huge amounts of water.”

Manufacturers are now working on technologies to solve this problem, says Wezel. He is confident that they will succeed.

For Wezel, it is clear where the demand for hydrogen-fired turbines will come from. “We have no other solution for seasonal, long-term backup generation, for example in winter periods when there is no sun and little wind. Batteries are not suitable for that.”

Gas market package

The question is, though, how do you ensure that energy companies will invest in hydrogen-based backup generation so that it will be available when it is needed?

“That is a task for the European Commission,” says Wezel. The EC is expected to start work on a “EU gas market package” next year – a set of legislative proposals as a follow-up to the electricity market design package which was finally adopted by the EU in March 2019 after years of negotiations. “What we need is a roadmap, preferably including a target, for renewable gas. This would foster higher amounts of renewable gas as well as investments in power-to-gas-to-power and by this give our members the confidence they need to invest millions in developing new technologies. Additionally, it must be clear how the value of backup generation can be monetised.”

For electricity producers, the turbine manufacturers’ guarantee that they will be able to retrofit gas turbines to run on “renewable” gases is of crucial importance, notes Wezel. “When they invest in a gas turbine today, they can be sure it won’t become a stranded asset. We will make sure it can always be converted to be used with hydrogen and biogas.”

That may give some assurance to electricity producers. For natural gas suppliers, however, the development of hydrogen turbines is not necessarily good news: it is one more alternative for the use of natural gas.

|

Initiatives in hydrogen gas turbines Swedish electricity company Vattenfall is working with its Dutch subsidiary Nuon on a project to convert one of the three units of its gas-fired power plant Magnum in the northern Netherlands to make it suitable for 100% hydrogen. This Hydrogen to Magnum (H2M) project, which aims to be ready by 2023, is supported by MHPS (Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems), Equinor and Gasunie. MHPS will build the turbine, Equinor will produce the hydrogen by converting Norwegian natural gas into hydrogen and carbon dioxide and storing the carbon dioxide in underground facilities off the Norwegian coast. Gasunie is carrying out research to explore how the hydrogen can be transported to and stored at the Magnum power station. At the same time, Vattenfall is working on a research project with Italian turbine manufacturer Ansaldo Thomassen, Technical University Delft, Opra Turbines, Nouryon (formerly AkzoNobel) and Emmtec, called “High Hydrogen Gas Turbine Retrofit”. This aims to build a “cost efficient” fuel burning system that can use any combination of hydrogen and natural gas: from pure hydrogen to pure natural gas. The project, which in April 2019 received a €500,000 subsidy from the Dutch government, works with the so-called “FlameSheet” technology developed by Ansaldo Energia. Vattenfall is also building a combined hydrogen production and energy storage facility, called a “Battolyser”, at the Magnum power plant. The battolyser “can efficiently store or supply electricity as a battery, but can also split water into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis,” Vattenfall has said. The produced hydrogen will be used for cooling the generators at the Magnum plant and will thereby replace the “gray” hydrogen (which is produced from natural gas) that is being used for the purpose. Eventually, Nuon wants to use hydrogen produced from renewable energy as a carbon dioxide-free fuel for its gas plant, the company has said. The battolyser was developed in 2016 by a team led Professor Fokko Mulder at Delft University of Technology. A recent article in Power Magazine, High-Volume Hydrogen Gas Turbines Take Shape, written by Sonal Patel, describes a number of other initiatives in hydrogen gas turbines in different parts of the world. The article notes that “In preparation for a large-scale power sector shift toward decarbonisation, several major power equipment manufacturers are developing gas turbines that can operate on a high-hydrogen-volume fuel.” It quotes several experts, who note that “efforts by companies like Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems (MHPS), GE Power, Siemens Energy, and Ansaldo Energia to develop 100% hydrogen-fuelled gas turbines have recently shifted into high gear, owing in part to new carbon reduction policies worldwide that have accelerated renewables capacity. The companies – which all manufacture large gas turbines but are jostling to sell them in a diminished market – are also actively competing for a concrete footing in future markets, including those that could thrive in a hydrogen economy.” Initiatives mentioned include projects by Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems (MHPS), Siemens, GE and Ansaldo Energia. The article notes that at a recent conference in Houston, MHPS “rolled out a market case for increased hydrogen use in the power sector, saying it wants to make hydrogen-fired gas turbines a key facet of a ‘global CO2 -free hydrogen society using renewable energy by 2050.” As MHPS president and CEO Paul Browning told Power Magazine, while natural gas will continue its significant role to address variability from renewables, the next phase of development will involve storage of electricity using hydrogen. Producing hydrogen from renewables through electrolysis – which uses excess renewable power to split a water molecule – allows for the ‘renewable hydrogen’ to be stored and used later in a combined-cycle gas turbine, he said. |