The Gas-as-a-Bridge-Fuel Pitch: Who Needs it? [Gas Transitions]

Who first thought of the idea of promoting natural gas as “bridge fuel”?

I remember that Shell launched a campaign promoting natural gas as “abundant, affordable and acceptable”. This must have been in 2012. In November of that year the Daily Telegraph published an interview with then-CEO Peter Voser, headlined: “Gas is abundant, affordable and acceptable. It's also the future, argues Shell chief Peter Voser”.

Responding to the news that the UK government was set to announce the construction of “20 new gas-fired power stations”, to replace coal power, Voser said: “In all of this we see very strong gas growth. It is really driven by availability – there is some 250 years of gas resources available. It is acceptable from a CO2 footprint point of view, producing 50% to 70% less CO2 than coal for example. It is affordable currently and in the longer term.”

In the promotional literature currently on its website, Shell does not talk about gas as a “bridge”, but it does refer to it as affordable, abundant and acceptable – although not in a single phrase.

But the roots of the gas-as-a-bridge narrative go a bit further back. And they have a rather unexpected source, according to an article by Jie Jenny Zou from the Center for Public Integrity published in October last year (“How Washington unleashed fossil fuel exports and sold out on climate”). One of the masterminds behind the gas campaign, Zou writes, was Ernest Moniz, Secretary of Energy in the Obama administration from 2013-2017.

Zou notes that in June, 2010, a team of researchers at MIT, led by Moniz, who was then a professor at MIT, published a 308-page “interdisciplinary study”, The Future of Natural Gas, which, as Joel Kirkland reported in Scientific American (on 25 June 2010), concluded that “Natural Gas Could Serve as ‘Bridge’ Fuel to Low-Carbon Future”.

Kirkland wrote that: “Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are encouraging U.S. policymakers to consider the nation's growing supply of natural gas as a short-term substitute for aging coal-fired power plants. In the results of a two-year study, released today, the researchers said electric utilities and other sectors of the American economy will use more gas through 2050. Under a scenario that envisions a federal policy aimed at cutting greenhouse gas emissions to 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2050, researchers found a substantial role for natural gas.”

According to Kirkland, “The MIT team of researchers was led by Ernest Moniz, a physics professor and director of the MIT Energy Initiative. Moniz's name often floats around Washington when it comes time to choose another energy secretary. A major sponsor of the report is the American Clean Skies Foundation, a Washington think tank created and funded by the natural gas industry.”

Pitching a win-win

Moniz’s MIT report did not come out of nowhere. Zou notes that “During the 2008 presidential campaign … advances in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking … created a glut. Industry responded by pitching fossil-fuel exports as a win-win that would benefit consumers and enhance American power. Helping to deliver the message was a coalition of White House advisers: academics such as Columbia University’s Jason Bordoff, energy gurus such as Daniel Yergin, and national-security experts such as John Deutch [former CIA director, then-board member at Cheniere] — all with links to firms profiting from the boom.”

At that time Moniz ran a think tank at MIT which, according to Zou, was “largely funded by the oil and gas industry”. Moniz’s think tank published its “Future of Natural Gas” study first in an interim version in June 2010. The official version appeared in 2011. The study’s major sponsor, notes Zou, “was the American Clean Skies Foundation, a group created by Aubrey McClendon — then CEO of Chesapeake Energy — as part of a multimillion-dollar effort to market natural gas as a climate solution. The study’s advisory board included energy bigwigs such as McLarty and John Hess of Hess Corporation, an oil and gas company.”

On August 2, 2017, US Energy Secretary Rick Perry presided over the unveiling of an oil portrait of his predecessor, Ernest Moniz. The painting highlights some of Moniz’s published work, including a seminal study, “The Future of Natural Gas.” (Photo: Simon Edelman/U.S. Department of Energy)

The “high-level findings” of the study were clearly very favourable for natural gas, and foreshadow the Shell “three A’s” campaign. The study concluded, among other things:

- There are abundant supplies of natural gas in the world, and many of these supplies can be developed and produced at relatively low cost. In the US, despite their relative maturity, natural gas resources continue to grow, and the development of low-cost and abundant unconventional natural gas resources, particularly shale gas, has a material impact on future availability and price.

- Unlike other fossil fuels, natural gas plays a major role in most sectors of the modern economy — power generation, industrial, commercial, and residential. It is clean and flexible. The role of natural gas in the world is likely to continue to expand under almost all circumstances, as a result of its availability, its utility, and its comparatively low cost.

- In a carbon-constrained economy, the relative importance of natural gas is likely to increase even further, as it is one of the most cost-effective means by which to maintain energy supplies while reducing CO2 emissions. This is particularly true in the electric power sector, where, in the U.S., natural gas sets the cost benchmark against which other clean power sources must compete to remove the marginal ton of CO2.

- In the U.S., a combination of demand reduction and displacement of coal-fired power by gas-fired generation is the lowest-cost way to reduce CO2 emissions by up to 50%. For more stringent CO2 emissions reductions, further de-carbonization of the energy sector will be required; but natural gas provides a cost-effective bridge to such a low-carbon future.

- Increased utilization of existing natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) power plants provides a relatively, low-cost short-term opportunity to reduce U.S. CO2 emissions by up to 20% in the electric power sector, or 8% overall, with minimal additional capital investment in generation and no new technology requirements.

- Natural gas-fired power capacity will play an increasingly important role in providing backup to growing supplies of intermittent renewable energy, in the absence of a breakthrough that provides affordable utility-scale storage. But in most cases, increases in renewable power generation will be at the expense of natural gas-fired power generation in the US.

The rest, as they say is history: when Moniz became Obama’s energy czar, in 2013, he “spearheaded the administration’s ‘all-of-the-above’ policy, which endorsed drilling alongside renewable energy”, writes Zou. “When he became secretary in 2013, among his top priorities was fast-tracking approvals for natural-gas exports — as advocated by industry lobbying groups such as the American Petroleum Institute as well as pro-export studies published by think tanks such as the Brookings Institution and the Center for Strategic and International Studies…. Under his watch, the Energy Department moved swiftly to foster LNG exports in 2013 before shifting its focus to decades-old restrictions on the export of crude oil. Days after the Paris climate agreement was reached in 2015, Obama signed a budget bill to keep the federal government running; slipped inside was a provision allowing crude oil to be sold freely for the first time since 1975.”

“Not clean, cheap or necessary”

Whether or not as a result of the gas lobby, global gas production has shown a steady upward trend in recent years, expanding 2.2%/yr on average in the period 2006-2016, according to the BP Statistical Review of Energy. US natural gas production grew by 3.8%/yr during that same period.

However, despite this success, the gas-as-bridge-fuel pitch may be said to have become somewhat threadbare. Gas industry proponents have sometimes expressed frustration with the bridge metaphor. They prefer to see gas as a permanent part of the energy system. At the same time, many environmentalists oppose the idea altogether. They argue that natural gas should be banned, period.

The Washington DC-based NGO Oil Change International (OCI) came out with a report on May 30 which presents a frontal attack on gas. It’s called: Burning the gas ‘bridge fuel’ myth – Why Gas is not Clean, Cheap or Necessary. The report “makes the case that gas is not a ‘bridge fuel’ to a safe climate. As the global climate crisis intensifies and gas production and consumption soars, it is clearer than ever that gas is not a climate solution,” it says.

Does OCI have a case? Let’s follow the reasoning in their report. They present 5+1 arguments “why gas cannot form a bridge to a clean energy future”. They start with the methane issue, noting that methane leakages may be worse than thought and may reduce or negate the advantage gas has over coal in terms of CO2 emissions. But “even in the hypothetical case of zero-methane leakage”, gas, they write, should be phased out as quickly as possible.

Their five major arguments are as follows:

1. Gas breaks the carbon budget

This is probably the most important argument. It is illustrated with a graph of the “carbon budget” under a 1.5 °C and 2 °C degree scenario:

This graph shows, according to OCI, “There is no room for new fossil fuel development – gas included – within the Paris Agreement goals.”

Gas proponents, however, may argue that it’s coal (and oil) that need to be slashed first of all, leaving room for natural gas. But according to OCI, this argument does not hold water.

2. Coal-to-gas switching doesn’t cut it

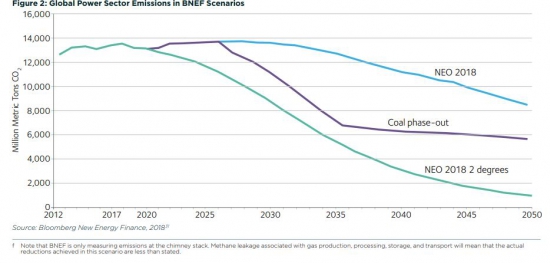

Concentrating on the power sector, OCI notes that according Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s (BNEF) New Energy Outlook 2018 (NEO 2018), a total coal phaseout by 2035, in which gas would fill 70% of the void left by coal, would lead to emissions substantially above a 2 °C scenario, as shown in this graph:

Looking at the entire energy system, OCI cites a “recent IPCC special report” (the Summary for Policymakers 2018, the link they give does not work, but the report can be found here), which shows two pathways aligned with 1.5 °C warming, both of which lead to a drastic reduction in the use of natural gas, as illustrated in this chart:

3. Low-cost renewables can displace coal and gas

An important reason why we can’t do without natural gas, according to gas proponents, is that only gas can replace coal on a large scale in the short to medium term. It would be too expensive , they argue, to replace “bulk generation” by renewables.

Not so, says OCI. The report cites the annual LCOE (levelised cost of energy) studies by financial advisory firm Lazard, which show a steady decline in cost of wind and solar compared with coal and gas power:

4. Gas is not essential for grid reliability

OCI also rejects the notion that gas power would be needed to ensure grid reliability. “The reality is that there are many choices for balancing wind and solar on the grid”, says the report, “and gas is losing ground to cheaper, cleaner, and more flexible alternatives.”

The report notes that “Most of the gas generation capacity being built today uses combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) technology”, but this is “the wrong technology for the energy transition”, because these power stations take a relatively long time to ramp up and are generally only profitable when running for a long time. They are therefore challenged by renewables rather than complementary with them.

As to gas peakers, these are increasingly challenged by batteries, which are faster and “cheaper over the lifetime of their operation”. A 2018 study by Wood Mackenzie, notes the report, “found that six and eight-hour battery storage systems, which are beginning to enter commercial operation today, can address 74% and 90% of peaking demand, respectively.”

“As battery technology evolves and installed capacity grows,” notes OCI, “additional gas-fired generation is not needed. As BNEF recently stated, the economic case for building new coal and gas capacity is crumbling, as batteries start to encroach on the flexibility and peaking revenues enjoyed by fossil fuel plants.”

5. New gas infrastructure locks in emissions

A final reason to stop investing in new gas capacity is that this will “lock in” carbon emissions for decades to come, says the report.

Incidentally, OCI is even more critical about LNG than about natural gas in general, because LNG production and transport leads to higher emissions and that there is no guarantee that LNG will be used to replace coal. So-called “renewable gases” – biomethane, biogas, hydrogen – are also regarded with some scepticism.

Donald Trump and Barack Obama

What are we to make of all this?

One shortcoming of the report, to my mind, is that it focuses almost exclusively on the power generation sector. Some 60% of gas is consumed in industry and heating. There is no discussion on whether these needs can be met by solar and wind. In addition, LCOE cost comparisons can be quite misleading, as Mark P Mills explains in this article in Natural Gas World. (For another interesting critical review of LCOE cost comparisons, see Mike Parr, “Diverting fossil fuel investments to renewables is not enough”, Euractiv, April 4, 2019.)

The report is also very quick to dismiss the option of carbon capture and storage (CCS). It notes that “scientists Kevin Anderson and Glen Peters conclude [in a letter published in Science] that bioenergy production and CCS both face major and perhaps insurmountable obstacles… Given that most of the few CCS pilot projects to date have proved more costly and less effective than hoped, many analysts now consider that wind and solar power, which are proven technologies, are likely to remain cheaper than CCS, even if CCS technology improves.”

It adds that “the recent IPCC [special] report warns that carbon dioxide removal deployed at scale is unproven, and reliance on such technology is a major risk in the ability to limit warming to 1.5 °C.” For these reasons, OCI concludes that “It is far safer to reduce emissions in the first place – and that means planning for the phase-out of gas.”

However, these arguments seem to be somewhat misleading. The paper by Anderson and Peters focuses on BECCS (bio-energy with CCS) and CCS in power generation. But most experts today agree that the business case for CCS lies in industry above all.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) actually released a report May 29, “Transforming Industry through CCUS”, which argues that CCUS (carbon capture, use and storage) in industry “is expected to play a critical role” in the low-carbon energy system of the future. The IEA report notes that “CCUS is one of the most cost-effective solutions available for large-scale emission reductions”. It expects “more than 28 gigatonnes of CO2 are captured from industrial processes in the period to 2060, the majority of it from the cement, steel and chemical subsectors.” This amounts to 38% of the emission reductions needed in the chemical and 15% in the cement and steel sectors.

Nor is the IPCC negative about CCS. The IPCC report does state (on p. 96) that relying on “carbon dioxide removal” would be a “major risk”, but this refers to BECCS (bio-energy with carbon capture) and afforestation, not to CCS or CCUS. In fact, in several of the IPCC pathways that are consistent with limited warming, CCS is included. The IPCC does have one pathway without CCS, but this is one where energy demand will be lower in 2050 than today, which is difficult to imagine.

Wake-up call

Having said all this, it seems difficult to deny that in a zero-emission world, the use of “unabated” natural gas will need to be reduced drastically, eventually to zero, even if the “eventually” will be further away than OCI imagines.

This means that, if the gas industry wants to remain a permanent part of the energy system, it will need to start making some serious efforts to reduce its emissions, for instance with the help of CCS. It is widely known that much more investment in CCS is necessary if this is to play a major role in emission reductions.

Just recently, Guloren Turan, general manager for advocacy and communications at the Global CCS Institute, issued a “wake-up call for CCS” on the website Euractiv arguing that “to achieve the scale and speed of decarbonisation needed, CCS will have a critical role to play.” Turan’s is hardly the first “wake-up call for CCS”. I have been seeing similar wake-up calls for many years.

So what’s holding oil and gas company back from investing in CCS? According to Turan, “projects are struggling with the lack of robust policy support needed to move forward”. That may be so, but since when do oil and gas companies need to wait for “policy support” to undertake projects? Why can’t they do it without “policy support”?

True, there is no “business case” for CCS as long as carbon prices are low, but maybe the effort should not be seen as a short-term business case in the first place?

Turan observes that “in power generation, the launch of the NET Power demonstration plant in Texas presents new opportunities to deliver zero-emission electricity. The natural-gas power plant aims to generate emission-free electricity at a competitive cost with conventional combined cycle gas generation.”

In addition, he writes, “CCS opens the door for a new energy economy with the production of hydrogen and the operation of zero-emissions power plants. Hydrogen can play an important role in decarbonising energy production, transport and domestic and industrial heating. Hydrogen from natural gas is a cost-effective and scalable solution. The large-scale production of hydrogen with electrolysis faces the challenge of the generating capacity of renewable energy and with water usage.”

Gas industry, what more encouragement do you need? You may want to keep in mind that the next generation of political leaders might not be as supportive of natural gas as Donald Trump – and Barack Obama.

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com

_f550x265_1559667561.JPG)

_f550x271_1559649943.JPG)

_f550x286_1559650008.JPG)