Tanzanian LNG at last? [LNG Condensed]

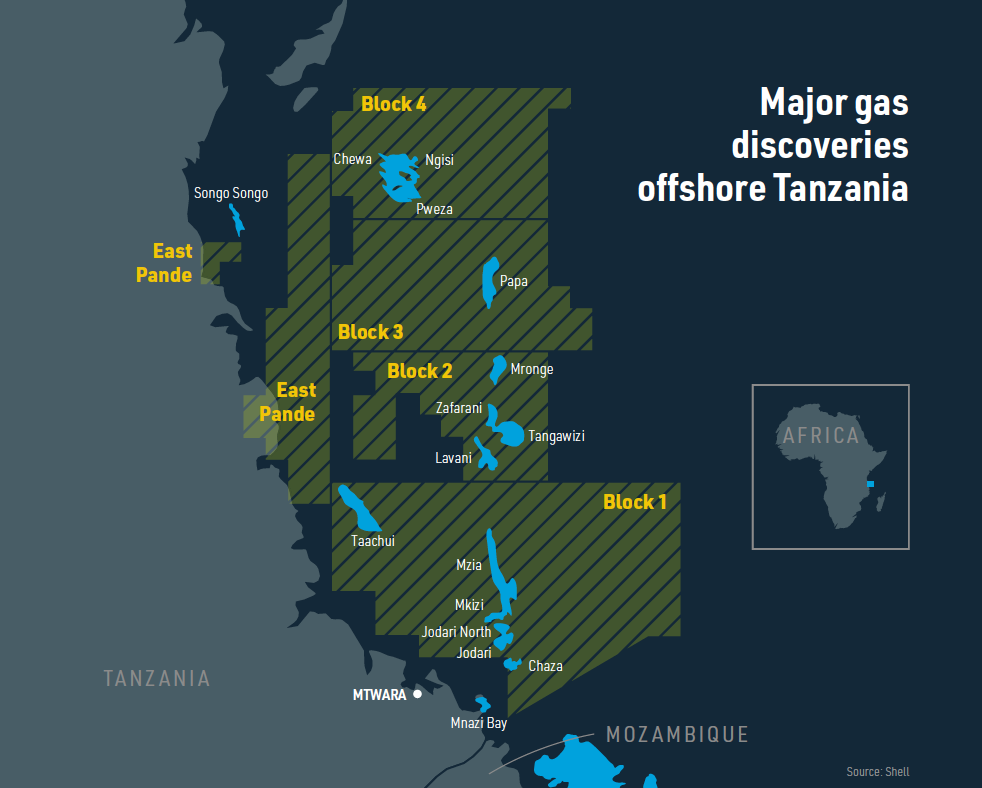

In total, Tanzania has 57 trillion ft3 of proven gas reserves, following a string of major discoveries since 2010 in its offshore Mafia Deep Basin, more than enough to supply the country’s growing stock of gas-fired power plants and supply a proposed LNG scheme. However, the government of President John Magufuli appears suspicious of large foreign investors and has pursued policies designed to maximise government control over any development. These policies have raised concerns about the stability of the country’s investment regime.

Multi-user project

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

In 2014, the joint-venture partners in Blocks 1 and 4 and Block 2 signed a preliminary agreement to cooperate on a combined onshore LNG plant. Mozambique had set the tone by opting for a similar multi-user project, but the size of the reserves held by the main two consortia involved made this approach an obvious option. Blocks 1 and 4 hold 16 trillion ft3 of recoverable gas, while Block 2 has 15 trillion ft3, meaning that they jointly had the potential to supply a big liquefaction facility, which would deliver economies of scale for all.

Norway’s Equinor operates Block 2 with a 65% interest, alongside ExxonMobil with 35%. Shell owns a 60% share in Blocks 1 and 4, with the remaining equity split between London-listed Ophir Energy (20%) and Singapore’s Pavilion Energy (20%).

In March, Ophir announced that it had accepted a takeover offer of £408.4mn ($539mn) from Indonesia’s Medco, having rejected an earlier bid in January. Medco’s acquisition of Ophir was expected to be complete in May.

The state-owned Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) has the right to farm in to all blocks with a 10% stake, and may also take a stake in the proposed LNG plant.

There have been occasional reports that ExxonMobil wants to sell its stake in Block 2 because of delays in development and its desire to focus on its planned LNG project in Mozambique, but no official statements to this effect have been released. Even if representatives of the US firm have made such a suggestion, it may merely have been designed to push the Tanzanian government into action.

Resource nationalism

As part of its African socialism, Tanzania pursued resource nationalist policies from the 1970s until the mid-1990s, but has embraced more market-driven economics over the past 20 years. Although the country has seen inequalities in income rise, the economy has grown much more rapidly since state control of key sectors was loosened.

Initially, progress on LNG in Tanzania was held up by the forecast oversupply in global LNG markets as a swathe of new Australian, Russian and then US LNG projects came on-stream. More recently delays have been caused by the passage of new legislation and the government’s hard bargaining approach.

The government began the process of drawing up new oil and gas industry legislation in 2015, but it has still to be finalised. The Permanent Sovereignty Act requires parliament to approve future agreements, presumably including LNG projects, while the government passed the Natural Wealth and Resources Contracts bill in 2017, allowing it to redraft contracts signed with private sector companies.

The situation is further complicated by the government’s recent record of making punitive financial demands against natural resource companies. Most notably, the government issued gold miner Acacia Mining with a $190bn tax bill claiming that it had under reported its shipments out of the country. This resulted in legal action and a much reduced $300mn payment was finally agreed. Government pressure also resulted in Indian telecoms company Bharti Airtel ceding 9% of its 60% share in Airtel Tanzania in January to the government, which now holds 49% in the firm.

In addition, Magufuli launched a review of the eleven gas contracts and concessions held by private sector companies in March 2018 and the government has indicated that it may insist on them being renegotiated. Moreover, last September, it legislated to outlaw international arbitration for disputes between the state and investors, and, in February, ratings agency Fitch downgraded its long-term political risk index for Tanzania from 64.4 to 60.5 out of 100 as a result. The government has also placed restrictions on the repatriation of money.

These changes to the investment regime have made reaching an agreement between the companies planning to develop the country’s oil and gas resources and the government difficult, particularly as it remains unclear whether upstream concessions will have to be renegotiated. The uncertain investment climate has also resulted in little interest in recent oil and gas licensing rounds, despite the apparent prospectivity of Tanzania’s offshore areas.

An Equinor spokesperson said in February: “An LNG development is a large project that requires large upfront investments. To ensure that all parties benefit from such a project, stable and predictable framework conditions for the more than 30-year lifetime of the plant is essential. We trust that the government of Tanzania has a long-term view on this major industrial investment.”

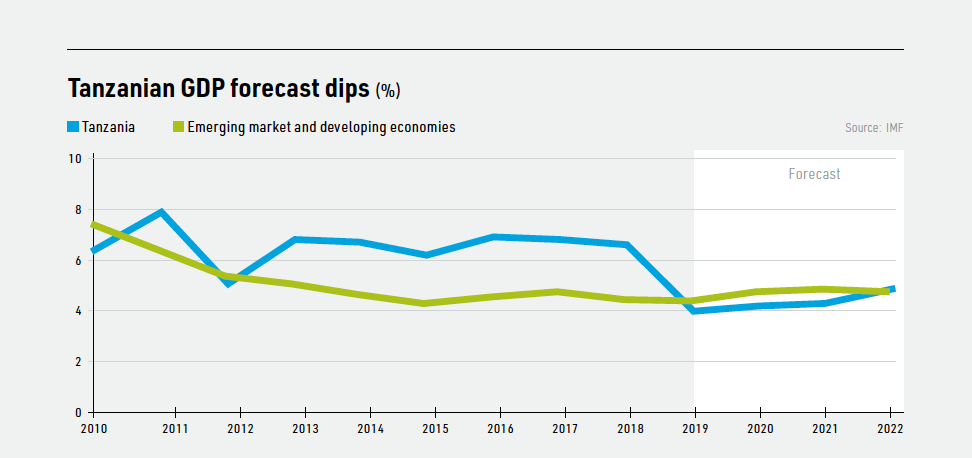

In April, the IMF reported that the Tanzanian government had refused to authorise the Fund’s latest report on the country. The IMF forecast in its latest World Economic Outlook that the country’s economy will grow by 4.0% this year, down from 6.6% in 2018. The Fund had previously forecast growth above 6% for 2019, if the government increased capital spending and improved conditions for foreign investment.

The government would stand to benefit hugely from the development of an LNG project, which needs both the expertise and capital of foreign investors. The Tanzanian central bank estimates that even just building the plant would add 2% to GDP, while the government calculates that the plant would generate about $5 billion a year in annual export revenues.

Slower GDP growth this year may prompt the government to take a more conciliatory line with investors. In addition, pressure to conclude a deal is rising as a result of a number of financial investment decisions (FIDs) on new LNG projects in the last six months in Canada and the US, which are starting to fill the forecast supply/demand gap expected to emerge in the early to mid-2020s. Mozambique too is making progress and FIDs are expected soon on its LNG projects.

New talks

Talks on developing the LNG plant have been held intermittently since 2017, but when the energy ministry announced in March that it would enter into direct negotiations with investors between April and September, officials appeared to have adopted a new approach. In May, energy minister Medard Kalemani suggested that progress may be possible when he said: “We are keen to get this key project for the country's sustainable economic well being off the ground as soon as possible”.

The talks are focusing on reaching Host Government Agreements (HGAs) relating to the rights and obligations of all sides over the development, construction and operation of the project. The TPDC has also suggested that the HGAs may be concluded in September, with construction due to begin three years later once off-take agreements have been signed and the front-end engineering design (Feed) process completed, with first exports forecast for 2028. This fits in with Equinor’s suggestion last year that it could take nine years from the conclusion of an HGA to the first shipment of LNG.

The government has already allocated 2,077 hectares of land for the plant in Lindi and has acquired the seven farms that previously occupied the area. Equinor Tanzania head of communications, Genevieve Kasanga, said: “We have been waiting for this chance for a long time and we have spent a lot of money for the project. Starting the negotiations gives us a hope to start the construction of the LNG plant.”

Domestic gas plans

A further motivation for the government is the desire to use some gas from the Mafia Deep Basin blocks domestically. Under the various production sharing agreements, investors are required to supply 10% of their gas production to the domestic market.

The Mozambican government has the same ambition, but appears to view domestic supply as a vague commitment rather than a concrete requirement. In contrast, Tanzania’s energy ministry has drawn up specific figures on how much of the country’s proven reserves it wants sold in which market: 1 trillion ft3 for residential use, 10 trillion ft3 for LNG, 4.6 trillion ft3 for petrochemical and fertilizer production, 9.1 trillion ft3 for power generation and 3.8 trillion ft3 for industrial use.

The government is particularly keen to see gas used as a domestic cooking fuel. At present, 71% of households use charcoal, 19% firewood and 10% LPG and electricity. Even 91% of the 5 million people living in the country’s largest city Dar es Salaam use charcoal. The energy ministry has set the TPDC a target of supplying gas to at least 25% of homes in Dar es Salaam within three years. At present, it operates just a few test projects.

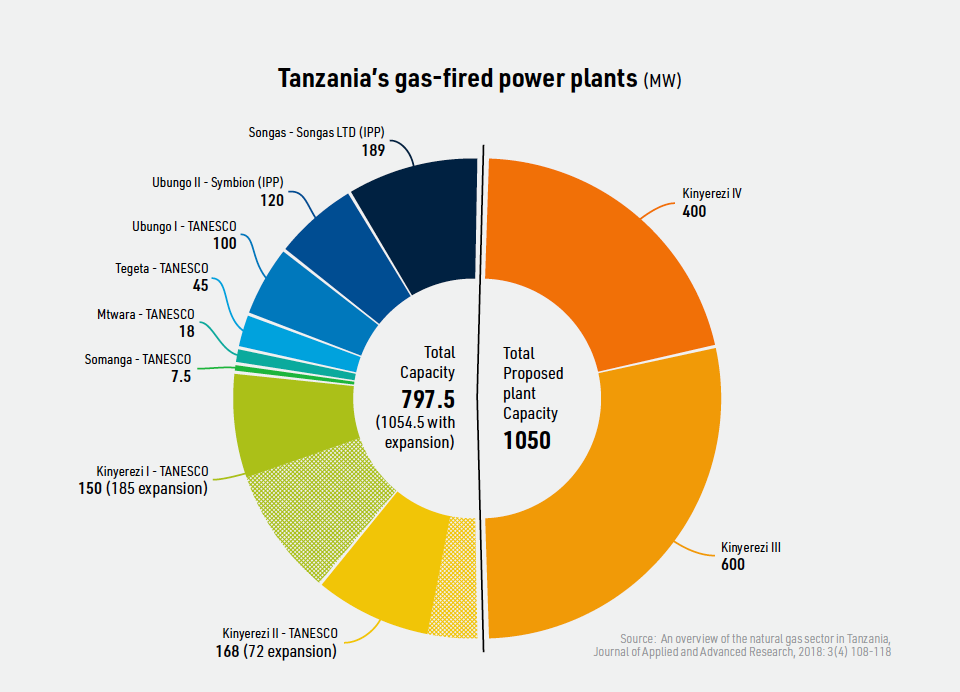

However, Tanzania is no stranger to natural gas, which it started producing in 2004 from the Songo Songo area, where gas was first discovered in 1974, and from Mnazi Bay in 2006, 24 years after discovery. In 2017, the country had 625.5 MW of gas-fired power plant, including East Africa’s largest gas-fired power station, the 189 MW Songas thermal power station.

The country in 2017 had total installed generating capacity of 1,450 MW, including 609 MW of hydropower and 188.5 MW of oil-fired generation. In 2018, a new 168-MW natural gas-fired power plant was opened outside of Dar es Salaam.

The Kinyerezi plant, the country’s first combined cycle gas turbine, was built by Japanese company Sumitomo with Japanese bank financing for 85% of the project. The new plant will push domestic gas demand up beyond the 300 million ft3 recorded by the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation for 2017. Plans have been proposed for two more plants of 600 MW and 450 MW respectively on the Kinyerezi site.

The county is also expanding its hydropower capacities. The National Environmental Management Council approved construction of the 2,100 MW hydro project at Stiegler’s Gorge in January, a project which has been on the drawing board for decades. Egypt’s Arab Constructors Company won the construction contract last year.

Tanzania Gas and LNG Project

The size of the LNG plant has yet to be determined, but the matter is likely to be addressed in the current talks between investors and the government, although most media coverage of the project cites a price tag of $30 billion. Preliminary plans for the project have named it the Tanzania Gas and LNG Project (TGP).

It would be built at Lindi, in the far southeast of Tanzania and very close to the Afungi LNG project site over the border in Mozambique, which will be shared by consortia led by US company Anadarko and Italy’s Eni. A 100km pipeline will be needed to pipe gas from the Equinor acreage onshore and it is possible that the other consortium could make use of the same line.

Shell announced in December that it still expected a single joint project to be developed and a spokesperson added: “All these blocks together hold sufficient gas to enable a shared onshore LNG liquefaction plant.”

However, it remains to be seen whether this will be a unitary LNG plant shared by all parties, or something along the lines of the project planned on the other side of the River Rovuma, where separate liquefaction trains are to be built for two separate consortia on a single site. In addition, Shell favours ‘a large project’, which presumably means at least two trains._f150x192_1560082915.jpg)

Neighbouring Mozambique looks almost certain to begin shipping LNG long before Tanzania, but while FID on Tanzanian LNG still appears some way off, its prospects currently look better now than for many years. However, progress still depends on both sides reaching an accommodation on what for the government will be a major new source of revenue and for the project developers a major long-life capital investment.