South Africa inches towards LNG imports [LNG Condensed]

South Africa’s 2018 Integrated Resources Plan stated that gas could account for up to 15% of the generation mix by 2030, but the version updated at the end of 2019 called for just 1 GW of new gas-fired capacity by 2023, which would require about 1.5mn metric tons a year of LNG, and another 2 GW by 2027, which would require a cumulative 4.5mn mt/yr.

Some of this demand could be met by domestic fields. In February, Total announced that its Brulpadda well, 175 kilometres offshore Mossel Bay in Blocks 11B and 12 B, had encountered 57 metres of net gas condensate pay, pointing towards 1bn barrels of hydrocarbons.

The discovery could be even more important in terms of encouraging further offshore investment as Brulpadda confirms the existence of large commercial reserves. Total described Brulpadda as a “world class gas and oil play”, which could be on stream sometime in the mid-2020s.

Total operates the concession with a 45% stake, alongside Qatar Petroleum (25%), CNR international (20%) and a South African consortium called Main Street (10%). A 3D seismic study will provide more data on the size of the find, while further wells are due this year to test its extent and other prospects on the block and on neighbouring acreage.

However, rather than displace potential LNG imports, the prospect of the discovery’s development could encourage gas consumption in the country, aiding the entry of LNG into the market.

Eskom’s travails

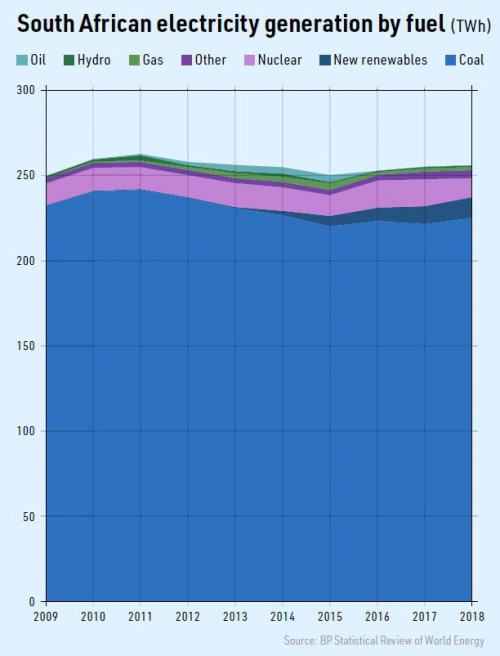

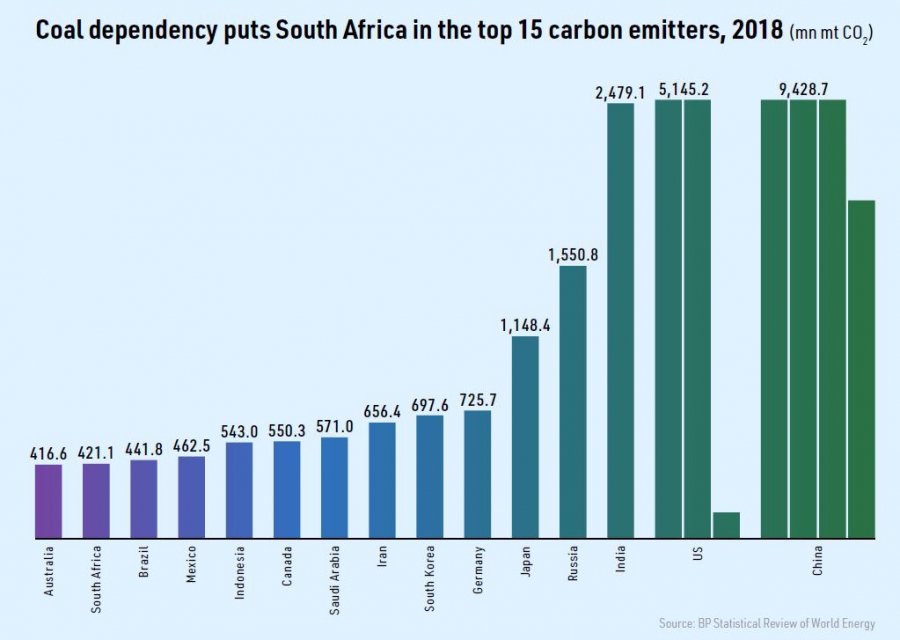

Any analysis of South Africa’s future gas demand makes little sense without some understanding of the power sector and the role played by heavily coal dependent state power utility Eskom.

The parastatal has long strained under the weight of its enormous debt and looks set to be broken up, paving the way for a more competitive power sector with a bigger role for gas. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has announced that Eskom is to be unbundled into separate generation, transmission and distribution companies, but full details of the plan have not yet been released.

Pretoria has periodically injected more capital into the company, while Eskom has managed to secure R15bn ($1.4bn) in commercial loans this year to fund capital projects. However, the government is unwilling to take on Eskom’s debt, which stood at R450bn ($43bn) at the end of last year, equivalent to 15% of South Africa’s total sovereign debt.

In February, the department of public enterprises described the firm as “technically insolvent”, as its revenues were insufficient to cover its operating costs. The situation must now be even more perilous since South Africa’s coronavirus (Covid-19) shutdown prompted a 9 GW fall in national power demand.

At the same time, majority state-owned transport utility Transnet is seeking to increase the price it charges Eskom to rail coal from mines to its power plants by 400%. The government is pushing both companies to move more coal by rail than by road.

New coal plant?

Eskom’s financial problems and its inability to complete current projects, combined with environmental concerns, all put in doubt whether any new coal plant will be constructed.

South Africa has more coal-fired capacity than the rest of Africa put together, but Eskom has struggled to complete its current coal plant construction projects. All units at the 4.8 GW Kusile and Medupi plants were due to come on stream by 2017-18, but the former still only has one of its six-pack units in operation and the latter three.

In addition, while coal has traditionally been considered a cheaper feedstock than gas, all of the country’s coal plants are located a long way inland, next to coal mines in Mpumalanga Province and now also Limpopo Province in the far north. There are significant transmission losses in transporting power from there to the coast, where two of the three main conurbations are located – Durban and Cape Town.

As a result, South Africa has experienced regular power rationing, while Eskom has been unable to export as much electricity to the rest of the Southern African Power Pool as previously expected.

Project costs have also run out of control: calculations vary, but the cost overruns certainly go into tens of billions of rand, or billions of US dollars, on each project.

Moreover, many of Eskom’s ageing coal-fired plants are due to be decommissioned over the next decade, unless they can be repowered. They could even be adapted to run on natural gas. The government also wants existing diesel generators to be converted to natural gas.

Increasing competition

There has already been significant diversification in South Africa’s coal-dominated power mix. With current generating capacity of 52 GW, coal’s share has fallen from 95% in 2006 to 77% today.

Five gas-fired plants were built in coastal areas in 2007 and 2015-16, to give total gas-fired capacity of 3,450 MW, while there has been a lot of investment in solar and wind power in recent years. Independent power producers (IPPs) dominate the renewables sector. The 335 MW Dedisa and 670 MW Avon projects became the country’s first substantial gas-fired IPPs when they were completed in 2015 and 2016, respectively, by French-owned but UK-based Engie Energy International.

In addition, various attempts to expand the country’s existing nuclear power generating capacity beyond the 1,860 MW offered by the Koeberg plant have faltered, so all new capacity is likely to be provided by renewables and gas, with the possibility of importing more hydroelectricity from Mozambique and, more speculatively, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The government’s long-term power strategy is unclear at the moment, but it seems that Pretoria is relying on gas to accompany the expansion of wind, solar PV and concentrated solar power capacity.

Mozambican gas

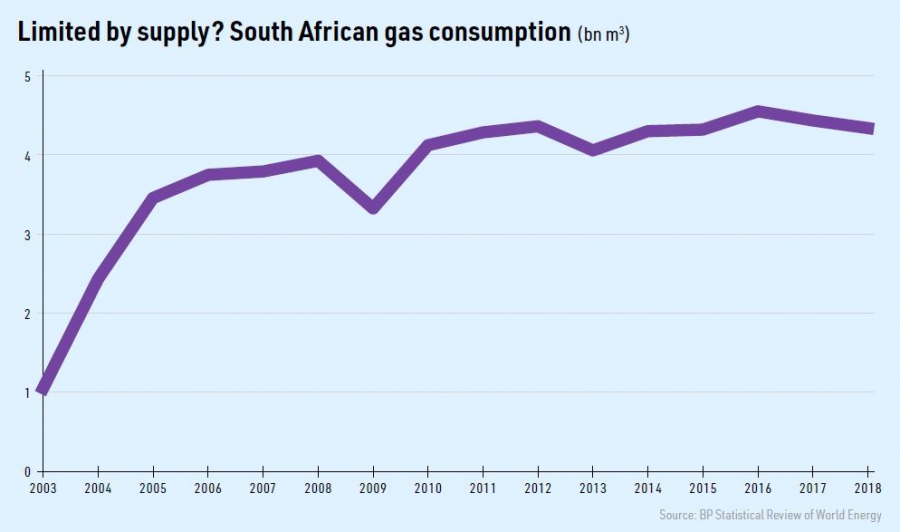

South Africa’s gas-fired power plants have so far relied on feedstock from South Africa’s established, but relatively small offshore fields. In addition, synthetic fuel producer Sasol currently pipes gas from the Pande and Temane fields in the far south of Mozambique to its Secunda gas-to-liquids plant in South Africa via an 865km pipeline, with some gas sold to residential and industrial consumers around Gauteng, where Johannesburg is located. In 2018, the country consumed 4.3bn m3 of gas, of which 3.9bn m3 was imported by pipeline.

Large gas discoveries in the Rovuma Basin in the far north of Mozambique over the past decade have the potential to satisfy South Africa’s gas demand. Proven reserves currently stand at 4.3 trillion m3 and with virtually no local demand, the focus to date has been on LNG exports.

Mozambique’s industrial and power sector demand for gas is relatively small and heavily concentrated in the south of the country, in and around the capital Maputo.

A north-south pipeline with an extension to South Africa has been mooted, but there are considerable obstacles, including the 1,728km distance between the Rovuma coast and the capital; and the fact that it will have to pass through very underdeveloped areas en route in a country where everything runs east-west rather than north-south.

Armed conflict also intermittently re-emerges between government forces and Renamo guerrillas, while – most recently – Islamist militants have launched deadly attacks in the far north, including on gas industry targets.

All this makes for physical and infrastructural barriers and a lack of security for what would be a vulnerable pipeline. If it is not feasible to pipe gas from the Rovuma Basin to the south of Mozambique at this stage, it seems very unlikely that a pipeline to South Africa will be considered.

Construction could also only be justified if substantial volumes were involved. The north-south pipeline to Maputo and on to South Africa would only make sense in the longer term if the security situation improves and the target markets have already been opened up by LNG or greater domestic South African gas production.

Gas shortage looms

Transnet plans to launch a tender this year for a contract to develop the country’s first LNG import terminal, either as an onshore facility or a floating storage regasification unit, with first gas due in 2024. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) helped fund the design, finance, construction and operation pre-feasibility study.

Transnet executive manager oil & gas business development, Jabulani Sithole, said that the gas will be needed by Sasol as supplies from the Pande and Temane fields are set to decline from 2023.

The Industrial Gas Users Association of Southern Africa agrees that South Africa could face gas shortages from 2023 and predicts a shortfall of 2.5bn m3 a year by 2025. A special purpose vehicle is to be set up to finance the regasification project through debt and equity financing.

Sithole said that Angola and Mozambique were potential LNG suppliers, while Transnet and the IFC have held talks with potential suppliers over possible options for project development. It is noteworthy that it is Transnet rather than Eskom that is the driving force behind the project, partly because it will involve reducing the country’s dependence on Eskom’s coal-fired plants, but also because Transnet holds the state’s responsibility for managing pipelines.

Some of the imported gas is likely to be used in power generation at the coast, but some will also be piped north to Gauteng.

Aside from power generation, imported LNG could be used at the Secunda gas-to-liquids (GTL) plant. South Africa’s national oil company PetroSA expects gas supplies to its own Mossel Bay GTL facility to run out by the end of this year. Another option would be to convert the plant from a 34,000 b/d GTL operation into a 46,000 b/d oil refinery, if a new source of gas supply is not available.

Transnet chief business development officer Gert de Beer said: “We are aware of the 2023 alert that Sasol has put out and we are working with Sasol to work out, how to sort out their own demand for gas...as well as the demand of the customers they are currently supplying.”

Terminal location

The LNG import terminal could be developed at the Port of Richards Bay, which lies between Durban and the Mozambique border in KwaZulu-Natal Province, or at the new port of Coega in the Eastern Cape, where a new gas-fired plant is under consideration.

Richards Bay could be an easier option because Transnet has suggested repurposing the old Durban-Johannesburg oil pipeline. A spur link could be built to Richards Bay. Alternatively, it could be transported along the existing 600km Lilly gas pipeline between Durban and Secunda. There is no spare space to build an LNG regasification plant at Durban because the port is hemmed in by the city.

A less likely but still possible option is for Maputo to be developed as an LNG import hub for South Africa, with gas supplied via a new pipeline between the Mozambican port and Gauteng. Maputo is actually closer to Gauteng than either of the KwaZulu-Natal ports: Durban and Richards Bay.

In November, Total and South Africa’s Gigajoule Power signed a joint development agreement to ship LNG to Maputo from northern Mozambique. Gigajoule previously signed a memorandum of understanding with Mozambique’s state-owned oil and gas firm Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos in 2013 to build the north-south line.

However, the chances of a South African LNG import terminal actually being developed could be affected by the Covid-19 crisis, which has severely affected the finances of both Transnet and the South African power sector.

At the same time, changes in Transnet management could affect the parastatal’s enthusiasm for the venture. The company was badly caught up in the wave of corruption allegations that has hit the country over the past few years, with the Transnet board and many senior executives forced to resign or sacked. A new group chief executive, Portia Derby, was appointed in February to overhaul the company’s management structure.

_f600x571_1591093701.JPG)