South Africa inches towards LNG imports [Gas in Transition]

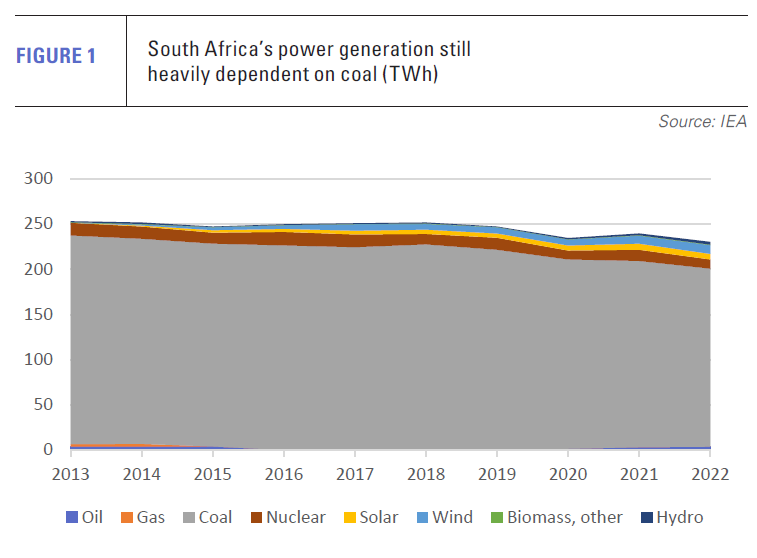

South Africa has long planned to shift its energy mix from coal to greater use of gas and renewable energy, but progress has been very slow. Coal still accounts for 85% of installed generating capacity, producing nearly 200 TWh of power out of a total of 235 TWh in 2022 (see figure 1). Wind capacity stood at 3.1 GW and solar at 6.3 GW at the end of last year.

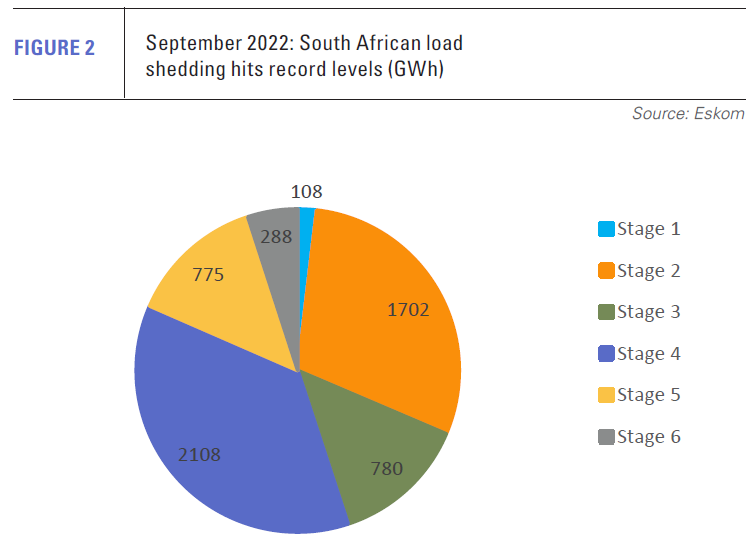

State utility Eskom continues to dominate the power sector, despite deregulation. This, and a stagnating economy, have deterred investment by independent power producers. Eskom’s large debts and the economy’s fragility have limited Eskom’s own capacity to invest. As a result, new generating capacity has been badly needed for two decades and periodic power rationing has become steadily more common (see figure 2).

Various strategies to address the shortages have come unstuck. For example, Eskom banked on the completion of two huge 4.8-GW coal fired plants, Medupi and Kusile. Both were badly delayed and subject to big cost overruns, as well as failing to reflect the shift towards a lower emissions power mix.

The utility also hoped to build new nuclear reactors in addition to the existing 1,840 MW Koeberg plant, but its enormous debts have been just one of the obstacles to their construction. Koeberg’s existing two units, which came online in 1984 and 1985, also now require expensive upgrades.

The government is under huge international pressure to avoid the construction of further new coal plants. At COP26 in 2021, it agreed to retire seven of its 15 coal-fired plants by 2030, but Eskom executives have suggested this will no longer be possible, owing to the growing severity of the country’s power shortages. At the same time, Pretoria is reluctant to weaken coal demand because of the employment and revenue the sector generates.

The government is under huge international pressure to avoid the construction of further new coal plants. At COP26 in 2021, it agreed to retire seven of its 15 coal-fired plants by 2030, but Eskom executives have suggested this will no longer be possible, owing to the growing severity of the country’s power shortages. At the same time, Pretoria is reluctant to weaken coal demand because of the employment and revenue the sector generates.

Gas supply and use in South Africa

All this has intensified pressure to develop gas-fired generation capacity. At present, Eskom’s portfolio includes just 2.4 GW of gas/liquids-fired capacity for peaking purposes.

In addition to domestic gas production, the country imports gas via the 865 km Rompco pipeline from the Pande and Temane fields in southern Mozambique, mainly for synthetic fuel production by South African firm Sasol.

Much bigger gas reserves have been discovered in the Rovuma Basin in the far north of Mozambique, but the proposed 2,600 km African Renaissance Pipeline (ARP) from the Rovuma to South Africa now looks unlikely to progress. Sasol decided last year to focus on imported LNG, possibly from the Rovuma, instead of the pipeline project. Sasol CEO Fleetwood Grobler said the ARP would have to be operated for 30-40 years to justify construction, but Sasol intends to use gas only for 10-15 years as a bridging fuel on its road to net zero.

South Africa consumed about 146bn ft3 of gas in 2022, according to Energy Institute data. The GlobalData Oil & Gas Intelligence Center says domestic production amounted to 32.5bn ft3 in 2022 down 5% on 2021, from five main domestic fields. As imports from the Pande and Temane fields are expected to fall from 2026, South Africa could be looking to fill a substantial gas deficit even before it considers increasing gas-fired generation both to meet existing power shortages and to reduce emissions by transitioning its power generation mix from coal to gas and renewables.

Offshore gas prospects look good

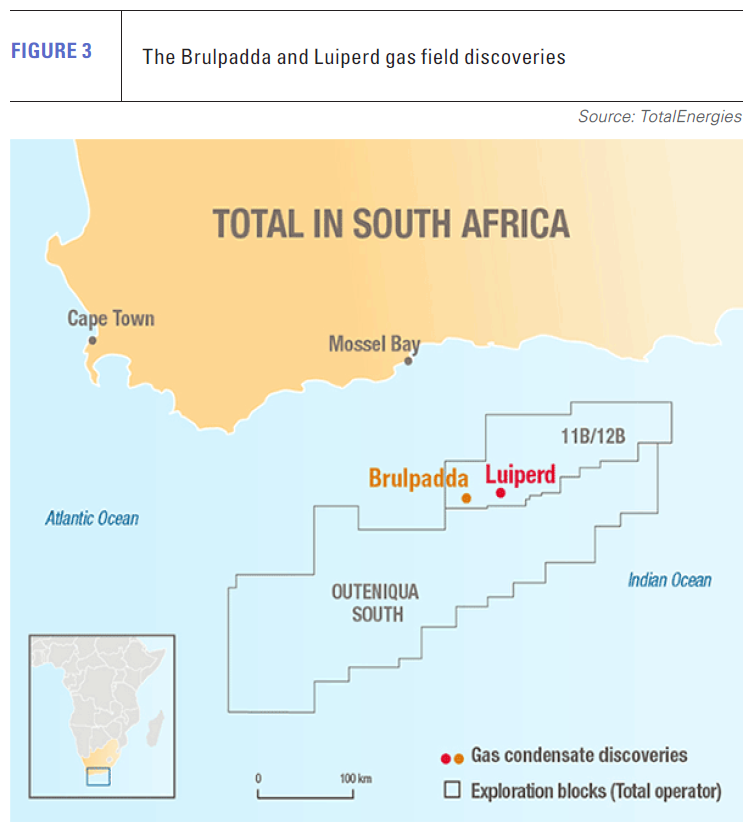

However, domestic production is expected to rise with the development of two major offshore gas and gas condensate fields discovered by France’s TotalEnergies in 2019 and 2020. The Luiperd and Brulpadda fields are estimated to hold 2.1 trillion ft3 and 1.3 trillion ft3 of gas respectively in addition to nearly 200mn barrels of gas condensate combined (see figure 3).

The first phase of development is expected to consist of three gas production wells on the Luiperd field linked to the existing F-A gas production platform owned by PetroSA, allowing early gas to land at the company’s Mossel Bay gas-to-liquids refinery. A second phase would see more production wells and construction of additional gas processing facilities.

Key questions are how much gas the two fields will produce and when. TotalEnergies, which is still assessing the fields, has not said, but Phindile Masangane, chief executive of South Africa’s Petroleum Agency has suggested 0.5bn ft3 over 15 years, which would mean 182.5bn ft3/yr. Other estimates suggest 100,000 boe/d, which implies 219bn ft3/yr.

These figures are probably over-optimistic, and the gas will not all arrive at once, but there is no question that the fields are large. There is also a real possibility that the Paddavissie Fairway, located in Block 11B/12B, provides additional major discoveries.

A final investment decision on the two fields had been expected in 2023, but seems to be slipping into 2024 – perhaps awaiting publication of the gas master plan and the conclusion of the COP28 conference in Dubai – which would imply limited first phase production in 2026, owing to the use of existing infrastructure.

Over a ten-year time frame, it is possible that South Africa will start to meet a substantial proportion of its gas needs from offshore domestic production.

The need for LNG is more immediate. This is particularly so because, in 2020, the government set out plans to secure 11,813 MW of new generating capacity by 2030, including 3 GW of gas-fired capacity. In November, the government said it aimed to fast-track the new gas fired generation.

Pretoria announced in October that it had at last completed the gas master plan, but it is being considered by cabinet before its official release and the launch of the public consultation process. The plan is expected to include proposals to convert decommissioned coal-fired plants to run on gas and backing for LNG import terminals.

First LNG projects

US major ExxonMobil and Dutch firm Vopak jointly agreed to investigate LNG import options in South Africa in 2020, but nothing has been announced by the partners since then.

However, TotalEnergies is due to take an FID by September 2024 on a planned floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) at Matola, part of the Port of Maputo in the Mozambican capital. The gas will supply the 2-GW Beluluane power plant at Matola, which is due for completion in 2026. The plant will export most of its electricity to South Africa.

In addition, a short spur pipeline will connect the terminal to the Rompco pipeline to transport gas to South Africa. The import terminal is to be developed in partnership with South Africa’s Gigajoule, probably in conjunction with Mozambican investors. An investment figure of $500mn has been quoted in the regional press. Binding sales agreements have not yet been concluded.

Karpower

The government launched its Risk Mitigation Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme in 2021 to secure additional generation capacity quickly in response to power shortages. Under the programme, Turkey’s Karpowership had three bids for a combined 1,220 MW of LNG-to-power projects accepted.

The company is now assessing locations at three ports: Richards Bay in KwaZulu-Natal (450 MW), Ngqura in the Eastern Cape (450 MW) and Saldanha in the Western Cape (320 MW). Each bid includes an FSRU and two powerships – vessels housing gas-fired power generation. The locations of all three projects are distant from inland Mpumalanga Province, which hosts most of the country’s coal-fired plants that provide the lion’s share of the country’s electricity.

Karpowership secured approval for its environmental impact assessment (EIA) on the first project, Richards Bay, at the end of October and now aims to bring the project online by the end of next year. EIAs for the other two projects could be approved soon.

The Turkish firm has set up a joint venture called Karmol with Japanese shipping line Mitsui OSK Lines that has bought four steam turbine LNG carriers from Australia’s North West Shelf project. At least two of the vessels are to be converted into FSRUs for use in South Africa. They will supply the South African national grid under 20-year contracts, although with five and ten-year early exit clauses.

As a result, South Africa’s switch to gas in the short term looks almost certain to be based on imported LNG, which will gradually be capped by new domestic production from its recently-discovered offshore fields, depending on the speed and extent of their development. South Africa’s LNG adventure may therefore mirror that of Egypt or Israel, but there is perhaps more scope, given the need for coal-to-gas switching in the power sector for long-term LNG imports.

Domestic LNG production

In August, Afro Energy, which is owned by Australia’s Kinetiko Energy, signed a non-binding term sheet with Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa, a national development finance institution. The aim is to develop an onshore LNG project to supply 50 MW of energy equivalent within three years at a cost of A$138mn ($91mn), ramping up to 500 MW within a decade, with options for a further 1,000 MW energy equivalent.

Afro Energy says that it has 2.1 trillion ft3 of gas in place to supply all 1,500 MW. Kinetiko aims to develop both conventional gas and coal bed methane (CBM) across Southern Africa in the longer term.

There is also growing potential for LNG in the region’s large logistics sector. South African firm Renergen completed its own small Virginia LNG project in Free State Province in 2022. Using local reserves, it is producing 50t/day of LNG in the first instance, rising to 680t/day in Phase 2, with all output distributed to haulage firms via filling stations, in order to displace diesel use. Phase 2 will also include the construction of a 60 MW gas-to-power plant to utilise the gas.

Despite apparently plentiful CBM reserves in South Africa and neighbouring Botswana, little progress has been made on tapping them to date and domestic LNG production plans remain relatively small-scale.