Russia, Japan and LNG [NGW Magazine]

Since the beginning of Putin’s tenure and even before, Moscow’s interests were mostly in Europe, where pipeline gas would be more competitive than LNG. But the problems that emerged after 2014, coupled with the strides forward made in LNG transport and trade, led Moscow to take another look at Asia. The search for investment and markets led Moscow to closer co-operation with Tokyo.

The problem with China and other Asian markets

The interest in a gas line to Japan, from Sakhalin to Hokkaido arose from problems with the market in Europe. Although the Kremlin had been engaged in negotiations with China, there were delays as China did not want to pay as much as Europeans. The conflict in Ukraine has accelerated Russia’s dramatic reappraisal of the Asian market and the perception of China as an important back-up. After 2014, Russia decided to build a gas line to China regardless of the fact that China did not want to buy gas at the high, oil-indexed prices that would have applied in 2014. Russia most likely made considerable price concessions to China and embarked on the Power of Siberia. Russia’s interest in China was encouraged by the fact that by 2018, China had become the biggest importer of gas in the world.

As time progressed, and Russia’s access to European markets became less certain, China’s attraction grew. Heavy reliance on China however came with the risk of economic dependence leading to political dependence. The problem existed not only in dealing with China: other Asian markets also presented problems.

For example, Russia put much hope into sending gas to Turkey. But Turkey is already receiving gas from Azerbaijan through the TransAnatolian Pipeline (Tanap) and Gazprom’s market in Turkey has shrunk.

Russia has also wooed India.There is some danger that the gas line to send Turkmenistan’s gas to India via Afghanistan and Pakistan (Tapi) might be built and consequently, Russian observers have tried to comfort themselves with the notion that Turkmenistan was too greedy and India might not be interested in Tapi at all.

Even Novatek’s plans to send LNG to Asian markets have faced a variety of problems. Novatek presumably wanted to send most of its LNG to Asia. Still, the long Asia route makes LNG quite expensive and most of its LNG goes to European markets. Moreover, most of Russia’s Arctic projects exist only because of state subsidies. It is unclear for how long these subsidies will last.

All of this has impeded export of Russian gas, not just in Asia but to other parts of the globe and, if one would believe one of the reports, Gazprom decreased gas exports abroad.

Thus, on one hand, Russia apparently understands that the Asian market is not easy, and many problems exist. On the other hand, Moscow apparently has shifted its attitude toward LNG. In the past, Russian observers often stated that LNG could not compete with pipeline gas. Now, Gazprom became increasingly interested in LNG instead of gas transmitted through gas lines.

Russia also planned to improve logistics for sending LNG from the Arctic to Asia. Russia is planning to create a powerful icebreaker to help deliver LNG to Asia. In 2019, Russia increased gas production, including LNG, and engaged in search of other potential markets; Japan has emerged as one of them.

Japan's quest for LNG

Japan has clearly a strong interest in LNG. In the aftermath of the catastrophe at the nuclear plant at Fukushima, Japan increased its imports, most of which came from Qatar and were not cheap. Accordingly, it tried to diversify its gas suppliers. In 2018, Japan started to buy gas from the US, and in 2019, from China, and Japan apparently thought about other suppliers, including Turkmenistan, despite the obvious logistical problems. Indeed, in 2019, Turkmenistan and Japan discussed a variety of projects, including those related to gas. Russia has clearly emerged as a potential source.

Japan and Russia's gas

Tokyo’s relationship with Moscow has been complicated by the fact that Japan still has a territorial claim to Russia: the Kurile Islands were seized by Japan after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 and retaken by the USSR in the final days of the Second World War -- and retained after Japan’s defeat.

Japan still does not recognise this land as part of Russia, and Japan and Russia still have no official peace treaty. But economic interests have pulled Japan and Russia closer to each other. Japan has no oil and gas of its own, pending the hoped-for commercialisation of its gas hydrates. Russian gas and oil have attracted Japan for a long time.

Russia/USSR co-operation in extracting oil has a long history. In 1925 the USSR provided Japan with the concession to extract oil in Sakhalin. The agreement existed until 1943 despite the fact that Japan was allied with Nazi Germany and was ready itself to attack the USSR from the east. After the war, Japan apparently lost interest in Russian gas and oil. After various short-lived flirtations, interest in sending Russian gas to Japan re-emerged only seriously after Putin’s ascent to power. Japan has expressed an interest in building a gas line since 2001.

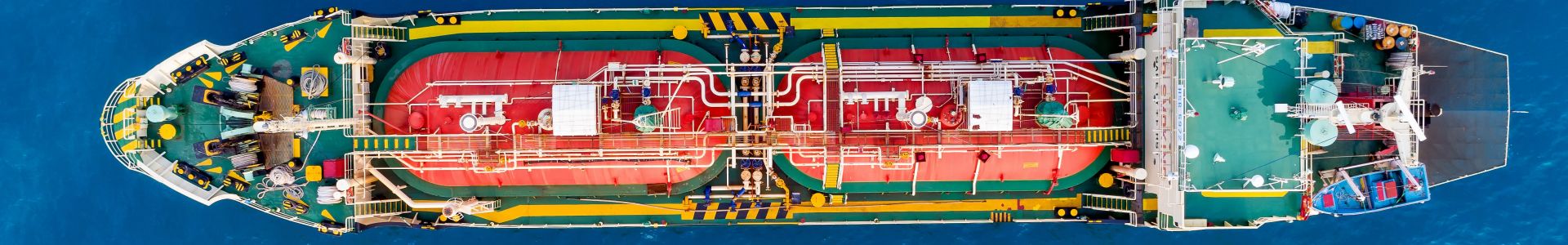

The beginning of true Russian/Japanese co-operation was launched in 2009, when Russia started to export LNG from Sakhalin-2. Mitsui and Mitsubishi were among the stockholders in the enterprise, although like their partners all their shares were halved when Gazprom entered the project with just over 50%. At the same time, Japan and Russia continued to negotiate, thinking about broader co-operation. In 2012 Japanese and Russian authorities once again started to discuss plans to build a gas line to Japan. Later, Japanese representatives stated that Japan was only interested in building an LNG plant in Vladivostok. But Japan remained interested in buying Russian gas this way or that. Consequently, Russia and Japan continued to engage in negotiations in 2014, 2017 and 2019. At that time, there were some tangible results, and in 2014 Japanese shipping company Mitsui OSK Lines together with a Chinese company participated in transporting gas from the Russian north.

In 2019, Yamal LNG sent a cargo of LNG to Japan. But as well as gas, Japan is also buying more oil and coal. The trend is not linear, and some observers believe that Japan has actually decreased purchase of LNG from Russia. Still, one could assume that the trends in opposite directions and Putin’s meeting with Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, in September 2019, was an important landmark that led to Japan’s plan to extract and buy more Russian gas. This was especially the case with LNG.

LNG and Abe's visit

One of the results of the visit was a Japanese firm’s plan to produce LNG in the Far East. Rosneft, anxious to secure an LNG business of its own, played a leading role in the development of the new project and signed an agreement with the Japanese company Sodeco among others to build an LNG facility near Khabarovsk. In addition, Rosneft and Japanese companies Marubeni Corporation, Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation, and Inpex Corp signed an agreement to engage in the search and extraction of hydrocarbons in the Far East. There was also an agreement to build a “gas and chemical complex in the far east of Russia.”

Gazprom also wanted closer co-operation with Japanese companies. Gazprom wants to expand the “Sakhalin-2” LNG plant and to “put new life into the Vladivostok LNG project,” although it is a project long assumed to have been shelved, despite the fact that Gazprom has taken what it called a positive final investment decision.

Novatek also benefited from closer co-operation between Japan and Russia. Japanese firms Mitsui and Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (Jogmec) decided to pay $3bn for 10% of the stock in Arctic LNG-2. The announcement was made after Putin’s negotiations with Abe.

Japan’s investments in Russian LNG have encouraged other companies to engage in the projects. In 2019 China National Oil and Gas Exploration & Development Corporation and China National Offshore Oil Corporation invested $12bn in Novatek’s LNG projects.

Japanese and Russian companies plan to co-operate in building LNG storage facilities. MOL and finance institution JBIC signed an agreement to build a transshipment facility for LNG in the Kamchatka and Murmansk regions, and Japanese company Saibu Gas has also discussed with Novatek the possibility of keeping LNG in its own storage and from there selling it to customers. Indeed, Japanese storage could be used for sending LNG to customers.

Both Tokyo and Moscow have various unresolved issues. But so far it seems, pragmatism has won out over geopolitical tensions, and Japan and Russia are seemingly going to co-operate more in extracting natural gas and marketing LNG.