Pipe dreams and the Levantine Great Gas Game [Gas in Transition]

Bringing non-Russian gas into southern and central Europe via the Southern Gas Corridor has been a long-standing aim of the EU, regional EU member states, Turkey and gas producers as far afield as Central Asia and the Middle East, albeit with significantly differing agendas.

Many projects, often grandiose, have been proposed over the years, often falling foul of the complex political and economic interests which crisscross the region. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 provided yet another twist to this Levantine Great Game, creating both new impetus for supply diversification and new infrastructure options as the Kremlin’s control over the pipelines originally built to bring gas west and south from Russia weakened.

Now, under plans hatched by southeast and central European states, the region’s growing gas interconnectivity could take another significant step forward, further weakening Russia’s once-iron grip on the region’s energy supplies. The ‘Vertical Gas Corridor’ would expand the capacity of the Greece-Bulgaria Interconnector (IGB) and use the Trans-Balkan Pipeline and other existing lines in Bulgaria, Romania and Ukraine to bring more Azeri gas and LNG into central European markets.

In doing so, it will directly challenge Russia’s last remaining major transit route into Europe – TurkStream.

Pipe dreams and outcomes

Pipeline plans connected with the Southern Gas Corridor have undergone huge and often unexpected transformations over the years. Gas producers dreamed of a Trans-Caspian pipeline to connect Europe directly with Turkmenistan or even an extension of the Arab Gas Pipeline through Syria to tap into Iraq’s under-utilised gas production.

Anxious not to lose markets in which it was the dominant supplier, Russia responded with its own monolithic plan, the South Stream project, which envisaged a capacity of 63bn m3/yr to supply Turkey and the rest of Europe. In the event major pipelines were built, but not those originally envisaged.

Today, the 1,850 km Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) brings Azeri gas to southern Europe across Turkey to the Greek border. The Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) transports Azeri gas onwards from Greece to Italy. And Russia’s TurkStream pipeline, consisting of two 15.75bn-m3 strings, supplies Turkey and countries in southeast and central Europe.

The importance of TurkStream to Russia has increased hugely as it has become the primary route for Russian gas imports into Europe, owing to the sabotaged North Stream, zero flows through the Yamal pipeline and heavily-reduced Ukrainian transits. In contrast to the decline or cessation of gas flows on other routes, those via TurkStream have increased.

Yet the desire to find an alternative to Russian gas is as strong, if not stronger, today than at any time in the past. Moreover, the aim now for some countries is total replacement rather than a degree of supply diversification. However, there are still differences in agendas, significant ones.

Hungary and Turkey pursue non-EU aligned pathways

Hungary is the cuckoo in the EU nest, Turkey the big bird watching from outside.

The EU has called for a voluntary phase-out of Russian fuel imports by 2027. Under the leadership of Viktor Orban, Hungary has continued to receive Russian gas imports and, in August 2022, signed a deal to increase supplies.

Russian gas continues to reach EU states via Ukrainian transits to Slovakia and through TurkStream and then the Balkan Stream pipeline – an extension of TurkStream – to Bulgaria and Serbia. The 8.5bn-m3 Hungary-Serbia Interconnector, commissioned in October 2021, allowed greater flows of TurkStream gas into Hungary. Of EU states, Hungary, Austria and Slovakia are now the biggest Russian pipeline gas importers.

Kiev has said it will not extend transit agreements when they expire at the end of this year. Hungary received 5.6bn m3 of gas via TurkStream and onward transit infrastructure in 2023, according to Russian sources, implying little current dependence on Ukrainian transits.

In addition, Budapest last August signed a deal with Turkey for the supply of gas through Bulgaria, which might, on paper, allow it to comply with the EU call for a phase out of Russian fuel imports.

Hungary’s gas deal with Turkey

Turkey is a gas importer with little domestic production, despite the recent start of Black Sea fields. Its dependence on imports and position as a gas transit country has raised questions as to whether Turkey will directly or indirectly export Russian gas to Hungary.

However, determining the origin of Turkish exports to Hungary will not be easy, nor do current sanctions prohibit the import of Russian gas from a third country.

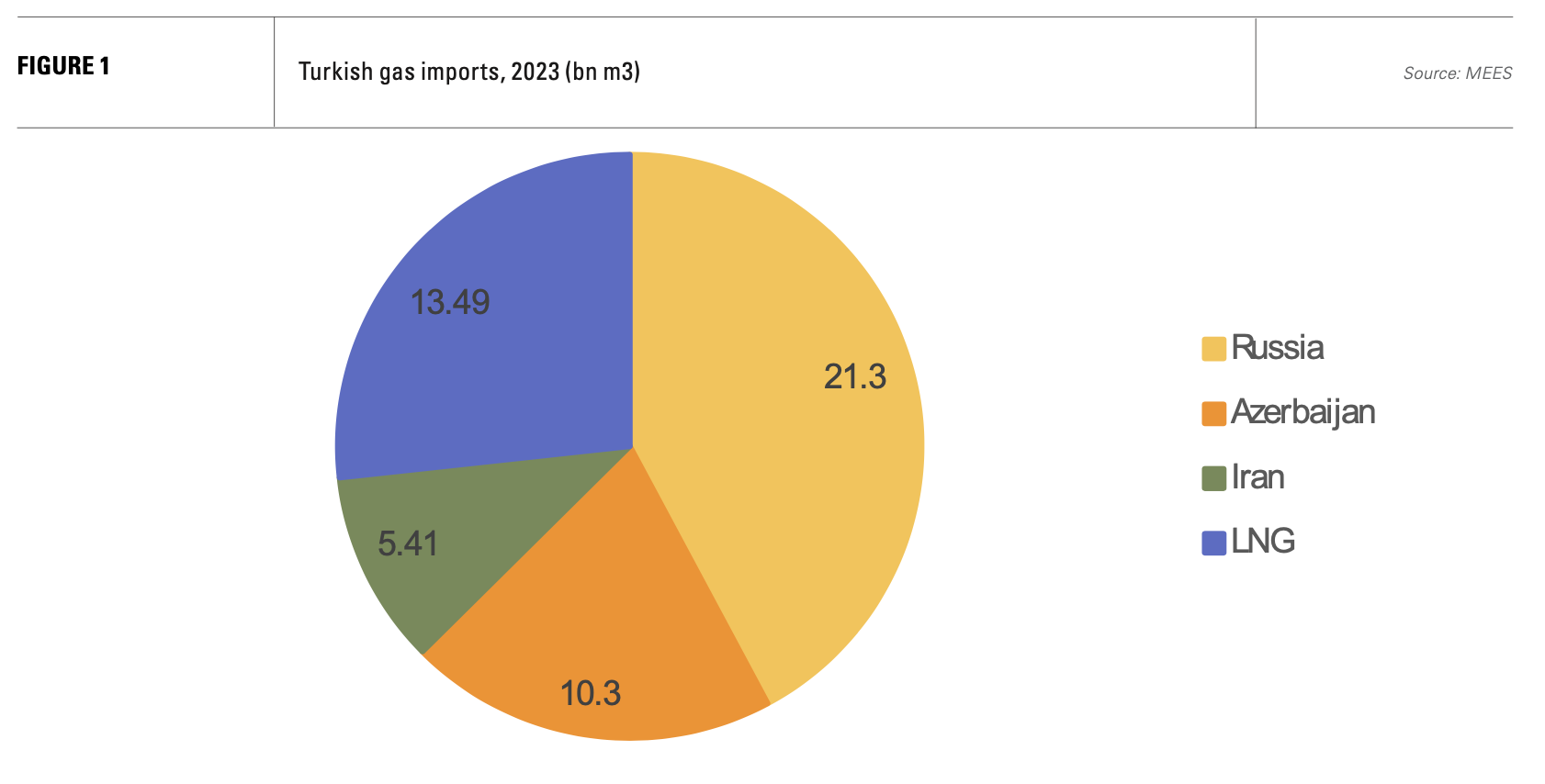

In addition to importing Russian and Azeri gas, Turkey has imported around 9.6bn m3/yr of gas from Iran, although this was reported to have fallen to a 14-year low of 5.4bn m3 last year (see figure 1). It also has five LNG import facilities with a total capacity of 30.3mn t/yr (see figure 2). There are plans to use the full 14bn m3 capacity of the Iran-Turkey pipeline, but ownership of that gas could be Central Asian via a swap agreement similar to the one which already exists between Iran and Azerbaijan.

.png)

As the exact origin of the gas reaching Hungary via Turkey may be obscured, Budapest’s deal with Ankara means Russia will likely maintain its gas sales volumes, Turkey will further its long-standing ambitions as a regional gas hub and the Hungarian-Russian friendship will endure.

Serbia, meanwhile, has embarked on a more ambiguous strategy, reflecting its desire to join the EU and consequent pressure to reduce its near total dependence on Russian gas. In November, the country agreed to purchase 400mn m3 of Azeri gas once an interconnector to the Bulgarian pipeline system is completed this year.

However, at the same time, it has pursued much closer economic and political ties with Hungary, particularly in the energy sector. Gas supplies under the new deal would have to rise significantly to offset Serbia’s current use of over 3bn m3/yr of Russian gas, but the agreement on Azeri gas supplies is at least a nod in the EU’s direction. Slovakia also appears to be wobbling over the loss of Russian gas imports.

What is clear is that the expiry of Ukrainian transit agreements will further increase the importance of the EU’s Southern Gas Corridor both as Russia’s sole remaining entry route into the EU and for those hoping to provide an alternative.

Vertical Corridor

The Vertical Gas Corridor countries are Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and … Hungary. In January, they were joined by Moldova, Ukraine and Slovakia. The plan is to expand the Greece-Bulgaria interconnector (IGB), which started operations in October 2022. Connecting with TANAP and starting at Komotini in eastern Greece near the Turkish border it goes north into Bulgaria. Initially it had a capacity of 1bn m3; flows in 2023 reached 1.5bn m3. The group intends to expand capacity to 5bn m3/yr.

In addition, the intention is to create bi-directional gas flow capacity connecting the IGB with Moldova and Ukraine’s large underground storage facilities, using the northerly sections of the Trans-Balkan gas pipeline, which formerly brought Russian gas south. Additional Ukrainian pipeline infrastructure would allow the gas to reach Slovakia and Hungary.

With the additional use of a reversed Trans-Balkan pipeline, flows to central and eastern Europe could reach 10bn m3/yr, its proponents say.

The IGB will rely on Azeri gas transported through TANAP and LNG imported into Greece as its primary sources to create a south-north gas connection from the shores of the Caspian to Ukraine. Additional gas supply could come from Romania, which is eying the prospect of net exports on completion of its Neptun Deep Black Sea gas project in 2027.

The LNG will come from Greece’s second LNG import facility at Alexandroupolis, which received its commissioning cargo in January with the expectation that commercial operations would begin in early March. The terminal is owned by Gastrade and its shareholders include DESFA, Greece’s public gas company DEPA and Bulgartransgas, Bulgaria’s TSO. The floating storage and regasification unit has a capacity of 5.5bn m3/yr.

The Vertical Gas Corridor is achievable not least because, in comparison with some earlier projects, it is small and the major more complex infrastructure on which it depends already exists.

However, it will take direct aim at TurkStream’s south and central European markets so will certainly raise Moscow’s ire. And, when the gas transit agreements expire, Ukraine’s gas pipelines may become direct military targets. With players sympathetic to Russia inside the Vertical Corridor club, and the inputs and outputs of Turkey’s gas system unlikely to be transparent, what happens next in this enduring Great Game remains hard to predict.

Nonetheless, there will be one visible indicator of the success or failure of European attempts to stem the flow of Russian gas into southern Europe – future volumes transiting TurkStream.