Oman to post record output [NGW Magazine]

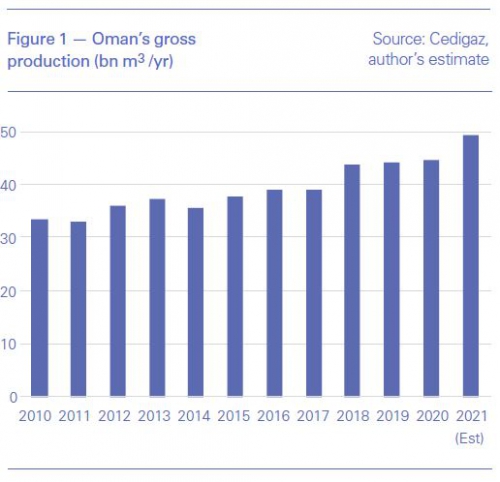

Oman is set for another, significant boost in non-associated gas production this year thanks to the startup of the tight gas and condensate field Ghazeer in late 2020.

Despite the adverse impact of Covid-19 lockdowns on Oman’s industries and economy at large, the sultanate is forging ahead with plans to make gas a bridge fuel for its economic diversification strategy.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Lower oil income in 2020 was a stark reminder of Oman’s overreliance on crude prices and also of the structural need to rationalise Oman’s gas pricing policy if its gas revival is to remain sustainable in the longer term.

LNG boost

As the second development phase of the giant Khazzan tight gas field commissioned by the UK’s BP in late 2017, Ghazeer adds 500mn ft³/d (5.1bn m³/year) and an additional 30,000 barrels/d of condensate production to Khazzan’s phase one – boosting overall plateau production to 1.5bn ft³/d, which is 40% of current domestic use.

With Ghazeer, Oman’s gas output is expected to reach around 49.5bn m³ in 2021.

Ghazeer started ahead of schedule in October 2020 and has capitalised on the economies of scale achieved by BP in Khazzan’s first phase. That is considered the first commercial, tight gas project in the Gulf, despite the high development costs and challenging geology.

Khazzan transformed Oman’s domestic gas balance in 2018, following years of supply shortages which led to gas being diverted from liquefaction and export.

Increased non-associated gas production is now expected to result in higher LNG sales, especially as Oman has been working on boosting LNG liquefaction capacity from 10.4mn metric tons (mt)/y to 11.4mn mt/y in 2021 through debottlenecking work at its three-train LNG complex of Qalhat, on the northeast coast.

The country’s ability to rein in gas demand for power generation partly through upgrading old gas-fired plants and partly through electricity tariffs reforms since 2017 also contributed to increased LNG exports. These remain a strategic source of revenue: LNG accounted for 16.7% of oil and gas export revenue in 2019, up from 15.8% in 2017, before the start of Khazzan.

Omani authorities are planning to extend the life of the Qalhat plant for another 25-30 years beyond the end of its concession in 2025. A fourth train has also been mentioned as a possible way to convert future surplus gas into cash.

The upcoming expiry of Oman’s oil-indexed long-term LNG means these will likely be replaced by shorter term and spot deals, exposing it to the volatility of spot LNG markets.

Oman will need to create a more consistent LNG strategy that gives a certain level of revenue predictability given the costs of non-associated gas production from tight and sour gas projects. These can be greater – at $4.5-7/mn Btu, all in – than the price achieved from domestic sales of around $3.5/mn Btu for industrial consumers and power producers.

However, as an established LNG producer, Oman has room to create competitive margins. “Oman LNG has already depreciated its investment [in its existing trains] and it has only operational costs which are very low and competitive,” says Siamak Adibi, head of the Middle East gas team at FGE consultancy. “The margin from LNG exports can be much higher than selling gas to the Omani domestic market,” he adds.

Horizontal drilling

Khazzan and Ghazeer have spurred renewed confidence in Oman’s upstream, with new entrants investing in its acreage over the past years and despite challenging and complex geology.

In one of the latest signs of confidence in Oman’s potential, US shale gas specialist EOG acquired 100% of interests in Block 36. The company is planning to start drilling its first two wells this year.

The deal with EOG came with other deals including Thailand’s PTTEP buying 20% of BP’s interest in early 2021 in Block 61 which covers Khazzan and Ghazeer. In 2018, the European majors Shell and Total agreed to develop resources from the Mabrouk North East gas field as well as in the Greater Barik area under a memorandum of understanding with the Omani government.

Production levels are initially expected at 500mn ft³/d and could rise to 1bn ft³/d, with the amount to be shared between Total who committed to build a 1mn mt/yr LNG bunkering plant at Sohar on Oman ‘s northern coast. Shell for its part proposed to develop a 45,000 b/d gas to liquids (GTL) at Duqm, a port in the south, which is a region set to host a number of new industrial projects. These are all part of the government’s Oman Vision 2040 to diversify the economy away from oil revenue and create jobs to reduce one of the highest unemployment rates in the Gulf.

The project has yet to be sanctioned, and in fact, Shell’s GTL project was dropped in late 2020 with uncertainty over commodities markets caused by the pandemic. CEO Ben van Beurden had said during the Q3 results presentation that the company would “remain selective in our investments in LNG and we don't expect to develop new greenfield gas-to-liquids projects anymore."

Shell had already dropped plans for GTL in Tanzania despite claiming success with the Qatar GTL project, the biggest of its kind.

But the GTL project looked challenging even before Covid-19 due to the risks inherent to the technology and the need for infrastructure. The Omani authorities have indicated that new monetisation options for Shell’s share of future gas output are under consideration.

Politically strategic

But the setback illustrates the underlying challenges associated with developing technically challenging gas resources as part of wider integrated schemes. For Oman, projects of this kind are more politically strategic than LNG because instead of exporting raw materials they increase in-country value through new, domestic revenue streams, and improve workers’ skills through an entire value chain.

In this context, gas is to play a key role as a feedstock and fuel for downstream industries such as petrochemical and fertilisers, for which demand is expected to rebound in the long-awaited, post- Covid-10 world. “The downstream uses of natural gas through the various commodities allow much less price volatility than the export of unrefined oil to the global economy as well. In particular, as with petrochemicals, this would provide added cushioning to the Omani economy,” a Middle East expert at Oxford University, Justin Dargin, said.

But low domestic gas prices remain a hindrance, and a challenge to navigate when introducing price reforms especially if the sultanate’s gas sector is to remain competitive for new industrial downstream investments. “If Oman does attempt to prioritise LNG production with the large-scale downstream gas projects without a coherent plan to expand domestic gas production and increase gas prices to rationalise demand, it could face another gas supply/allocation imbalance in the next decade,” Dargin concludes.