LNG market signals encourage the midstream [NGW Magazine]

As the market emerges from winter, global LNG demand is looking robust, buoyed by the relaxation of Covid-19 restrictions, coal to gas switching and significant falls in domestic production seen in some importing countries.

Meanwhile, the price volatility of recent months could put buyers off reliance on spot supply and give a boost to longer term deals, which may help new LNG liquefaction plants get off the ground.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

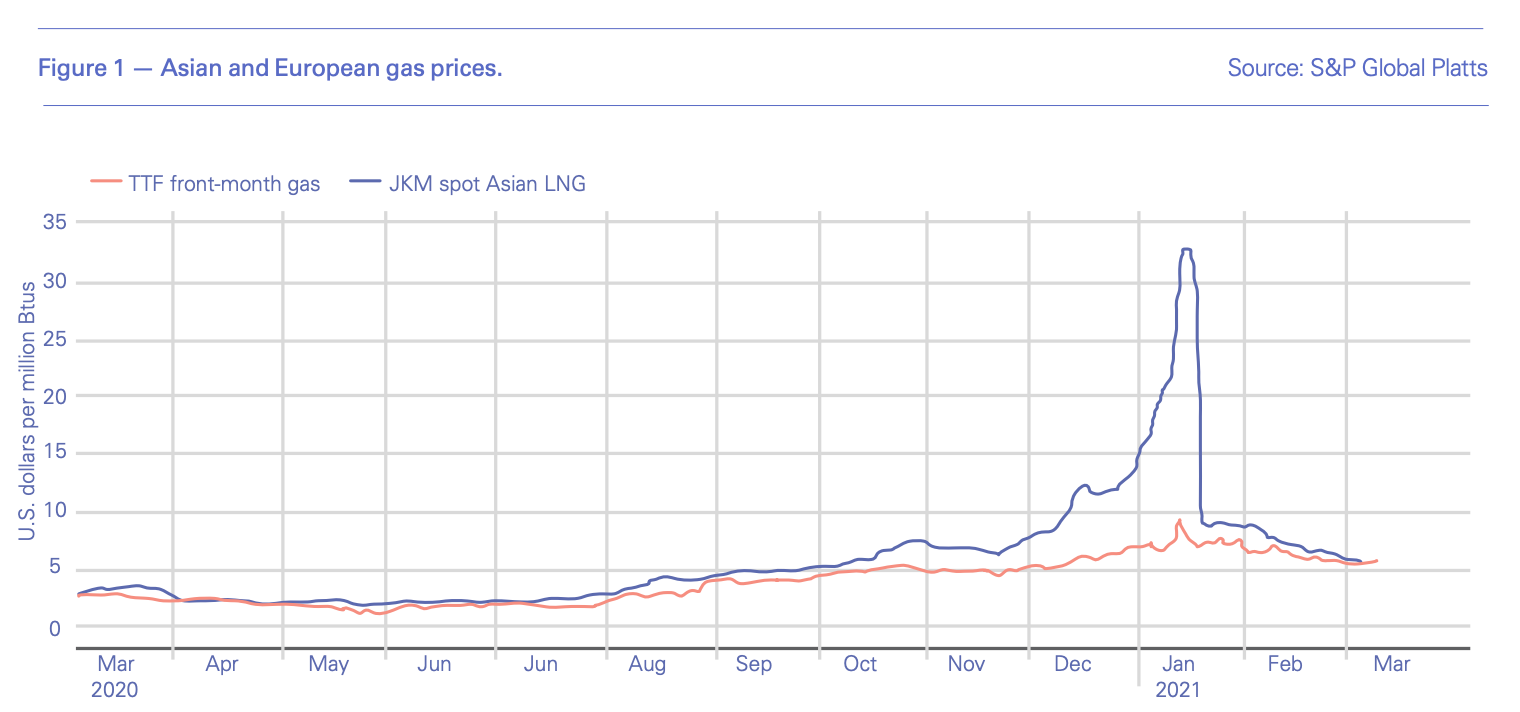

Gas prices in competitive markets – beyond the generally stable and low North American Henry Hub – have been on a roller-coaster ride over recent months. After dipping to record lows in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak last spring/summer, a gradual recovery in gas demand and disruption at several liquefaction plants helped spot prices recover in the second half of 2020 – rising above 2019 levels in Europe and Asia by October.

From then on, cold weather in northeast Asia saw LNG demand rise well above seasonal norms, driving up prices in both Asia and Europe. Low nuclear availability also contributed to demand in Japan, as did coal-to-gas switching in China and South Korea. China hiked pipeline imports from Russia, but restricted supplies from central Asia meant overall pipeline deliveries were below normal.

Limited LNG supply in the Asian region led buyers to look further afield, which pushed up freight costs and mopped up cargoes around the world – restricting the amount of LNG supplied to Europe.

At the peak of the cold weather, in the week ending January 8, S&P Global Platts spot LNG benchmark prices (known as JKM and covering month-ahead cargoes delivered to Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan) for February delivery hit a record high of $32.50/mn Btu (with rumours of cargoes traded as high as $40/mn Btu), although it quickly dropped back to $8.90/mn Btu two weeks later as temperatures recovered, and the delivery month switched to March (see chart 1).

Many buyers in Asia sat out the gas price spike, unable or unwilling to buy at such high levels – causing power shortages and the use of more polluting alternative fuels. Last year, the same JKM benchmark had dipped to an all-time low of $1.83/mn Btu in May during the first pandemic lockdown, which followed a lengthy period of low prices owing to oversupply related to new liquefaction capacity and relatively slow demand growth outside China. Japan also saw record high power prices in January.

The spike in Asian LNG prices caused a rise in European gas benchmarks, highlighting the growing influence of global LNG prices on European gas markets, which will only grow as domestic European output declines over coming years and LNG import capacity rises. Then, in late January and into February, Europe had a similar dose of low temperatures and high demand. But a rise in LNG deliveries as Asian demand eased, along with record stock levels, steady pipeline flows and high wind power generation prevented European gas and power prices spiking to the same extent as they had in Asia. Prices nevertheless were well supported, after record lows last summer.

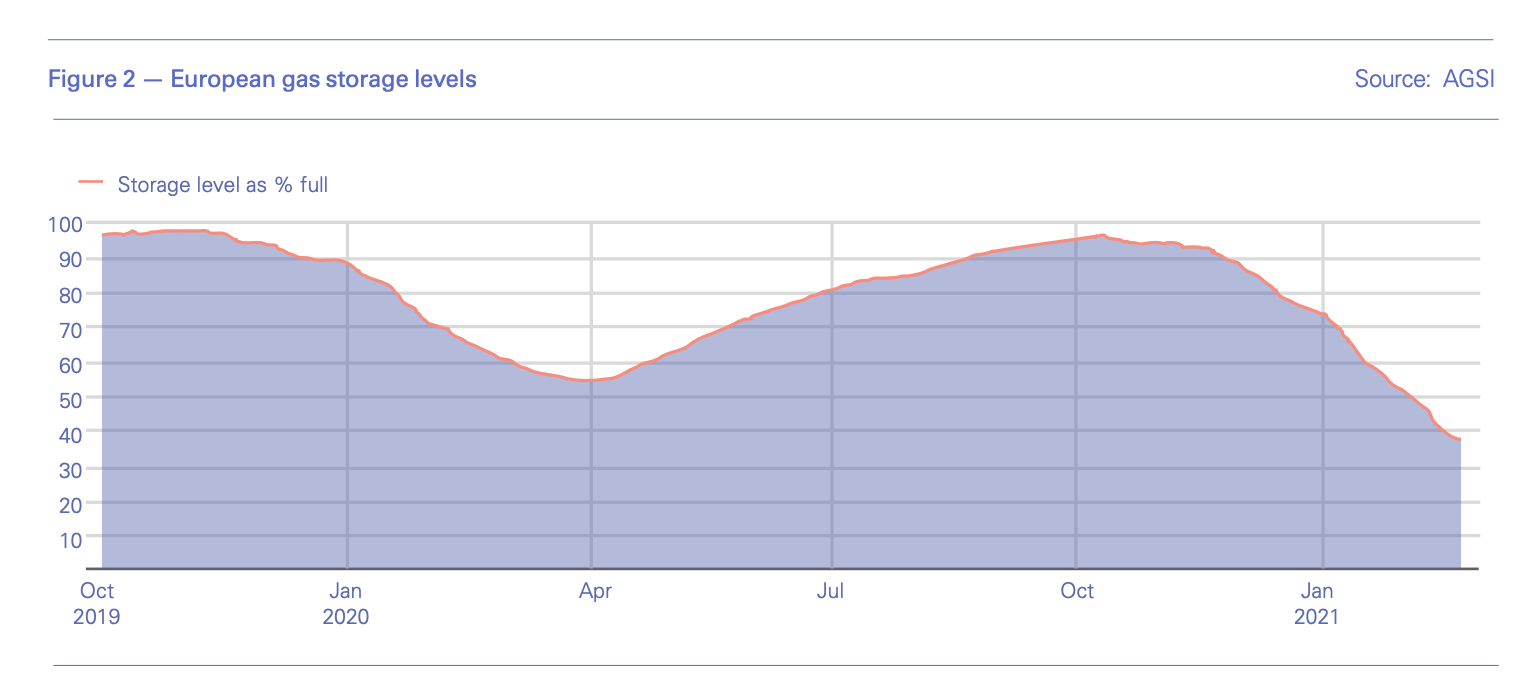

The situation led European stocks to fall sharply from the record highs seen through much of last year. By mid-February, stock levels had dropped to around 37% full compared to 60% full at the same time last year (see chart 2). By March 1 they were 406 TWh (close to the lows seen at the end of winter 2018), down from 667 TWh a year earlier and 457 TWh on March 1, 2019.

This large gap will require filling, helping to support prices this summer as gas is bought up to replenish the depleted stocks before the 2021/2022 winter season.

Extensive deferred maintenance from last year due to Covid-19 restrictions, and the delay to finishing the Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia to Europe, should also help provide support for European prices and LNG demand this summer. But LNG supply will have to compete with pipeline supplies to secure space in European storage, particularly early in the summer – when oil-linked pipeline supplies are likely to be cheaper given crude’s recent rise and the three- to six-month lag in term pricing.

South American, Asian demand on the rise

Low hydro reserves in Brazil and declining gas production from both Bolivia and the Vaca Muerta in Argentina look set to drive LNG demand growth, which could provide competition for Atlantic basin cargoes over coming months. Brazil already has new import facilities and Argentina is seeking to expand imports too, after hoping to switch to a net exporter. The state producer YPF has paid in order to terminate its contract with Exmar for the floating Tango LNG tanker.

And in China, gas switching, new import facilities and strong economic growth are likely to push LNG imports sharply higher again, after a big rise last year when they hit 67.4mn mt – up about 11% compared with 2019. Since late 2020, an additional 7.85mn mt/yr of import capacity has been added, lifting China’s total import capacity to 78.4mn mt/yr. This is expected to rise further to 107.9mn mt/yr by the end of this year. However, LNG imports will have to compete with a planned rise in Russian gas supply from the Power of Siberia pipeline, along with increased domestic output.

LNG demand was also up sharply in India in 2020, and will be further boosted this year by delays in domestic upstream gas projects and declining output from mature fields. Indian production fell to 78mn m³/d in 2020, down from 88mn m³/d in 2019. In northeast Asia, demand from both Japan and South Korea is expected to fall this year as they rely more on nuclear and coal-fired generation. For example, nuclear generation in South Korea is expected to rise by 8-16 TWh to 168-176 TWh.

Supply delays

Overall, the increasing demand is likely to outpace LNG supply additions this year and next, with less than 30mn mt/yr of new liquefaction capacity expected onstream in 2021-22. Plants started up so far this year include the 5mn mt/yr third liquefaction train at Corpus Christi in the US; and Petronas’ 1.5mn mt/yr PFLNG2 in Malaysia.

Further ahead there could be even more of a squeeze, with only 3mn mt/yr of new LNG capacity approved in 2020 thanks to the pandemic and or low prices, compared with up to 60mn mt/yr that had been expected, according to Shell.

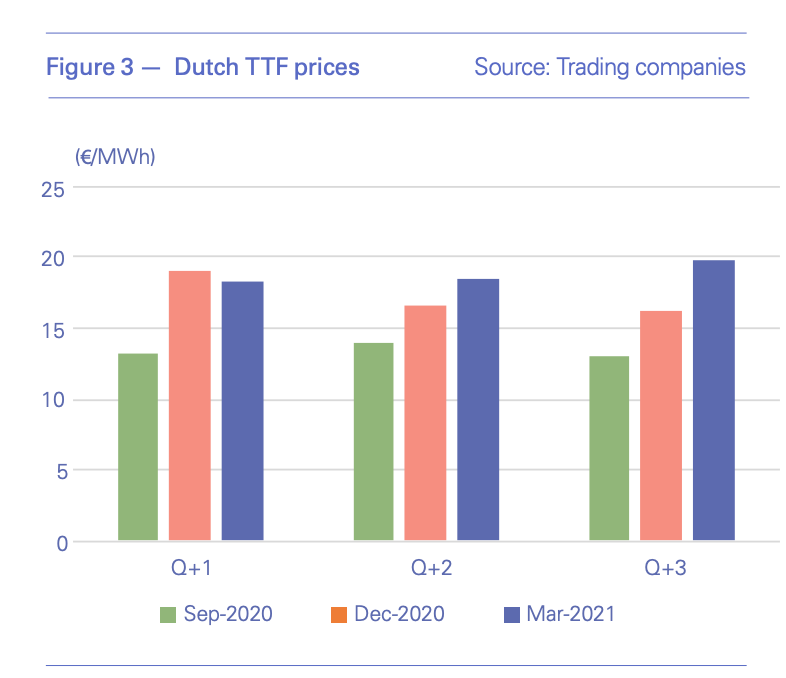

Following the tight winter market and supply delays, long-term European gas prices have strengthened from record lows last year, helped along by rising oil, coal, and carbon prices. In the UK, winter 21/22 gas reached 54 pence/therm (about $7.6/mn Btu) in early February, the highest level seen since early January 2020, with power for the same period trading at £61.80/MWh – although prices have eased back a little since then to £59.50/MWh at the beginning of March.

Prices at the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF) which is now Europe’s most liquid hub have also risen sharply since the lows of the summer. Forward quarters, which start the month following the month of assessment, have risen steadily since September 2019 (see Table 1).

EU carbon prices rose above €42/metric ton in early March – their highest ever – with gains attributed to continued bullish sentiment in energy and equity markets, as well as tightening EU environmental policies. This sharp increase is supporting gas as well as power prices, as it encourages the switch from coal to gas for power generation.

The gas price outlook is generally firm, with some analysts pointing to the beginning of a commodities ‘super-cycle’ fuelled by strong economic growth. Shell predicts global LNG demand will reach 700mn mt by 2040, as demand continues to grow strongly in Asia and gas extends its use into hard-to-electrify sectors. This anticipated growth means there is room for much more liquefaction capacity and could result in several quick final investment decisions if the pandemic loses its potency this spring/summer.

Spot price volatility sees buyers turn to term.

The recent spot gas price volatility has made many buyers and sellers much more wary of relying heavily on the spot market and could threaten the move toward more spot trade (which expanded to about one-third of the total LNG traded in Asia last year), and away from the traditional model of long-term, crude-linked LNG contracts.

As they seek to avoid price risk, buyers could be more inclined to sign up to the longer-term deals required to get LNG liquefaction plants off the ground. Some importers have already reacted to the spot volatility and changes in crude prices by increasing the volume taken under term deals – for example, China maximised term flow from Russia this winter as LNG prices spiked, while oil-linked Algerian deliveries to Italy reached 8.81bn m³ in October-February, compared with 9.32bn m³ for the full 2019-20 gas year. Alternatively, the market may seek a compromise in shorter, more flexible term deals, which could be priced against a variety of benchmarks.