[NGW Magazine] Keeping gas in the EU mix

The role of gas in Europe’s electricity sector: NGW interviewed Tatiana Mitrova, the director of the Energy Centre at the Skolkovo Business School and Tim Boersma, Director of Global Natural Gas Markets, Columbia University.

NGW had the opportunity to meet Tim Boersma and Tatiana Mitrova to discuss the role of gas in Europe’s electricity sector. They gave their views on why the golden age of gas did not play out in Europe; competition from coal and renewable energy; investment needs and the future role of gas in Europe.

You started your presentation at this year's Flame conference in Amsterdam mid-May talking about the influence of the US, policy issues and technology on gas and the global gas market. Can you elaborate?

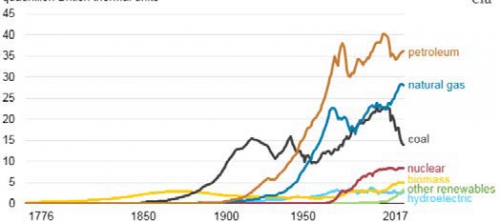

We mostly referred to the US because it is one of the places in the world where the ‘golden age’ in fact did materialise: low cost natural gas has pushed back the share of coal and, less decisively, nuclear in power generation, and provides an alternative in other parts of the energy economy, such as transportation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The impact of gas on US energy demand

Credit: EIA

You also said that the golden age of gas did not play out in Europe. But over the last two years gas has been experiencing a resurgence in Europe. What are the reasons, will it last and will it revive the fortunes of gas in the longer term?

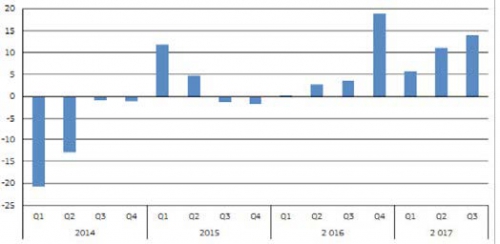

At a minimum it was less straightforward. Natural gas demand has indeed been growing again, but EU wide levels are still recovering from the early 2010s (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Growth in EU gas consumption

Credit: Eurostat

The economic downturn, cheap coal, and some mild winters were to blame. In recent years natural gas demand picked up as economic growth resumed, gas prices declined with abundant supplies available on the market, while at the same time coal prices, which were very low in 2014, recovered. If those fuel prices roughly hold, and efforts to reform ETS bring a more robust carbon price, the outlook for natural gas in the power sector is pretty good, though some economists are concerned that the next downturn may be around the corner. What is positive is that in most EU countries a realisation seems to have kicked in that there is a role for natural gas in the medium to long term, and ‘electrification’ is not the silver bullet that some had claimed it could be.

You made an interesting point about the extra cost of integrating large amounts of intermittent renewable electricity into the grid. What are these and is this going to be a limiting factor?

We mostly made that point because most studies that we have seen do not account for those costs, but they are real. Discussions tend to focus on subsidies for certain technologies, even though, as we point out, it is often challenging to have an honest debate about this, since pretty much all energy sources are subsidised directly or indirectly.

But a key characteristic of energy sources like the sun and wind is their intermittency, and absent options to store large amount of electricity this feature costs money: the grid operator needs to make an effort to balance the grid. Mostly, these costs are not included in calculations about the competitiveness of energy sources, and we believe they should.

You talked about the phasing out of coal in Europe. Is this really going to happen? The further away from western Europe you go the less likely this seems to be. What will drive it and what would be its impact on gas?

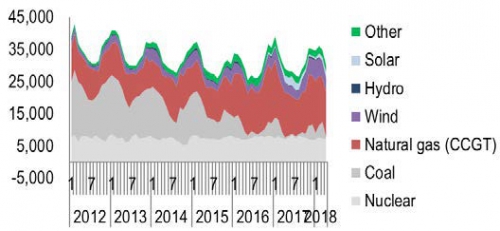

Eventually it will happen across Europe, but clearly some countries will move before others. The UK and France have a hard phase-out date in 2025, and it looks that most capacity in these countries will have shut down before then (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Decline of coal in UK power generation capacity

Then there is a group of countries, like the Netherlands, that have expressed aspirations, but will need to set these ambitions in stone. It is one thing to write in a policy document that coal plants need to be closed by 2030, as it did; but another to formally make that happen, knowing that the government gave investors the green light to invest only in 2007, and therefore they have not been able to make a proper return on investment.

Finally, there are countries, like Germany and Poland, that have struggled to come up with a viable pathway to substantially reduce coal use in their countries, but these countries in particular will struggle to meet their carbon targets, so over time the pressure to address this issue will likely build.

In countries where there is under-used power generation capacity available, phasing out coal is good news for natural gas, as the UK shows. When this is not the case, utilities face new investment decisions, and the picture is not as straightforward, given the long term uncertainties for natural gas in Europe.

In its latest report Oxford Institute of Energy Studies concluded that without decarbonisation gas will struggle to retain its foothold in Europe beyond 2030. Do you concur?

Writ large, yes, and this does not just apply to the EU. Most modelling work suggests that absent continued reductions in methane emissions, and absent the application of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies in both power and industry, it is difficult to reconcile natural gas with scenarios of deep decarbonisation beyond 2030.

You stated that high carbon pricing would have a negative effect on gas. How could carbon pricing work for gas? Will this be a decisive factor in the fortunes of gas in Europe?

Well, we stated that a high carbon price is not necessarily a boon for natural gas demand, as is sometimes assumed. In our scenario where we have robust carbon prices, combined with high natural gas prices, investments in renewable energy, without subsidies, in parts of the EU in fact make more economic sense. If gas prices are lower that makes them more competitive. This was one of the surprising outcomes of our work. Indeed, with high carbon prices gas easily defeats coal, but as a next step gas finds itself far less attractive than renewables.

What is the regional factor regarding the renaissance of gas in Europe?

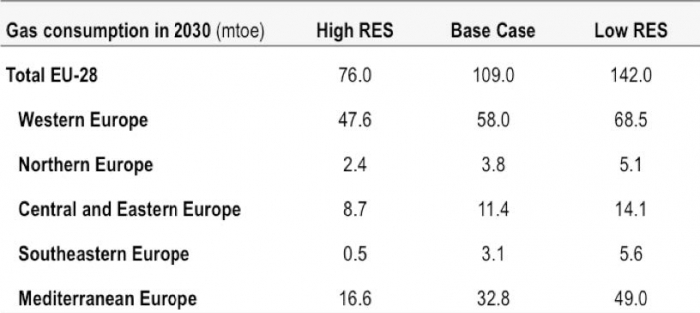

In our study we looked at the power sector, and electricity demand does not grow equally throughout the EU (Table 1).

Table 1: Gas consumption in different EU regions,based on high, base and low use of renewable energy sources (RES)

Typically, in northwestern Europe there is little growth, though that might change as governments push for electrification of space heating, and transportation. In the south and southeast of the continent power demand does grow, but here, ironically, renewables are also best positioned to compete, and gas and carbon prices matter. It is a fascinating landscape!

You made a strong point about the impact of gas prices, stating that if these rise further gas will become unattractive. And yet this is exactly what is happening now, but gas consumption and imports keep increasing. How do you see this in the longer term?

Well, in the near future the global gas market looks well supplied, and we think that translates into prices. But of course that could change in the medium to long term, and as domestic production continues to decline, mostly due to the major reductions in Groningen production in the Netherlands, imports as you say will rise, and this may translate into more robust, higher, natural gas prices.

If carbon prices rise similarly, that might not be favourable for natural gas in electricity generation. Renewables are getting cheaper, approaching grid parity with gas, so gas really needs to be more competitive in order to protect its market niche.

You said that for gas to remain competitive in power generation and to expand its market niche, the cost of LNG or pipeline gas delivered to the European border must be reduced dramatically to around $4 to $5/mn Btu. That's pretty drastic. Can it be achieved, and what would be the consequences if not? What price would kill gas in Europe?

I think more generally speaking cost reductions would be good news, particularly for companies shipping natural gas to Europe in the form of LNG. Major pipeline suppliers can probably break even around $4 to $5/mn Btu, but like to make a profit as well

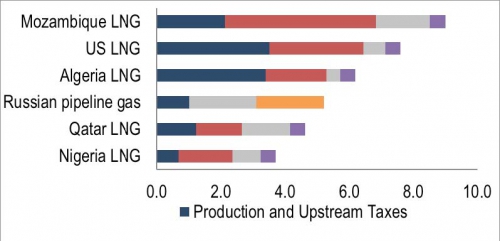

For gas to remain competitive in power generation, it has to reduce costs dramatically to around $4.5/mn Btu. Most LNG imports will struggle with this (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Long-run marginal costs of gas supply to Europe in 2025 ($/mn Btu)

There was a lot of talk at Flame about the use of gas during energy transition. Is this what is leading to the resurgence of gas now and how long will this transition last?

Well we observed a couple of things during Flame. One, indeed, was a lot of conversation about the role of natural gas in transition pathways. On aggregate, industry is more optimistic about that role right now, we think predominantly because among policy makers there is more realism about what can be done with ‘electrification’, and what is more challenging.

And second, we thought there was a remarkable amount of attention for ‘greening’ the gas portfolio, with lots of substantive debate about the potential for biomethane, and hydrogen. This was all very interesting and largely unparalleled elsewhere in the world. But if a two degree C world is to be realised, it is exactly that discussion that both industry and policy makers should be having, and so we thought that was positive.

With all of these uncertainties, how can investment in gas infrastructure in Europe be maintained, especially given the time needed to see returns?

Yes, this is really challenging, and we touch on this in our study. And interestingly it looks like the public sector is playing a more prominent role here, in the context of market liberalisation that has been in the works for over two decades. There are European institutions that co-finance infrastructure projects, for example through the Connecting Europe Facility. Some countries have designed capacity markets to prevent operators from closing capacity, and some member states are considering national subsidies.

All these questions revolve around the central issue: as we attempt to reduce the level of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and in particular carbon, in the coming years and decades, how do we make sure we preserve our standard of living, and improve that of people that are not as fortunate today as we are?

What is the future role of gas in Europe and what in your view should be done to strengthen this?

Natural gas likely has a role in Europe for decades to come. In electricity generation we believe this role will also be there, but increasingly under pressure, as our data suggests. In order to achieve this, cost reductions and improving the GHG footprint where possible are the two key steps.

Charles Ellinas