[NGW Magazine] Europe's war on coal

Burning coal for power generation in Europe is under threat as more countries set phase-out dates, carbon pricing incentives grow stronger, and emissions limits tighten. This will mean new opportunities for gas.

In November 2015 – just a few weeks before the COP 21 climate change conference at which the Paris Agreement would be signed – the UK’s then energy and climate change secretary, Amber Rudd, made a historic announcement. All unabated coal-fired electricity generation in the UK was to be closed down by 2025.

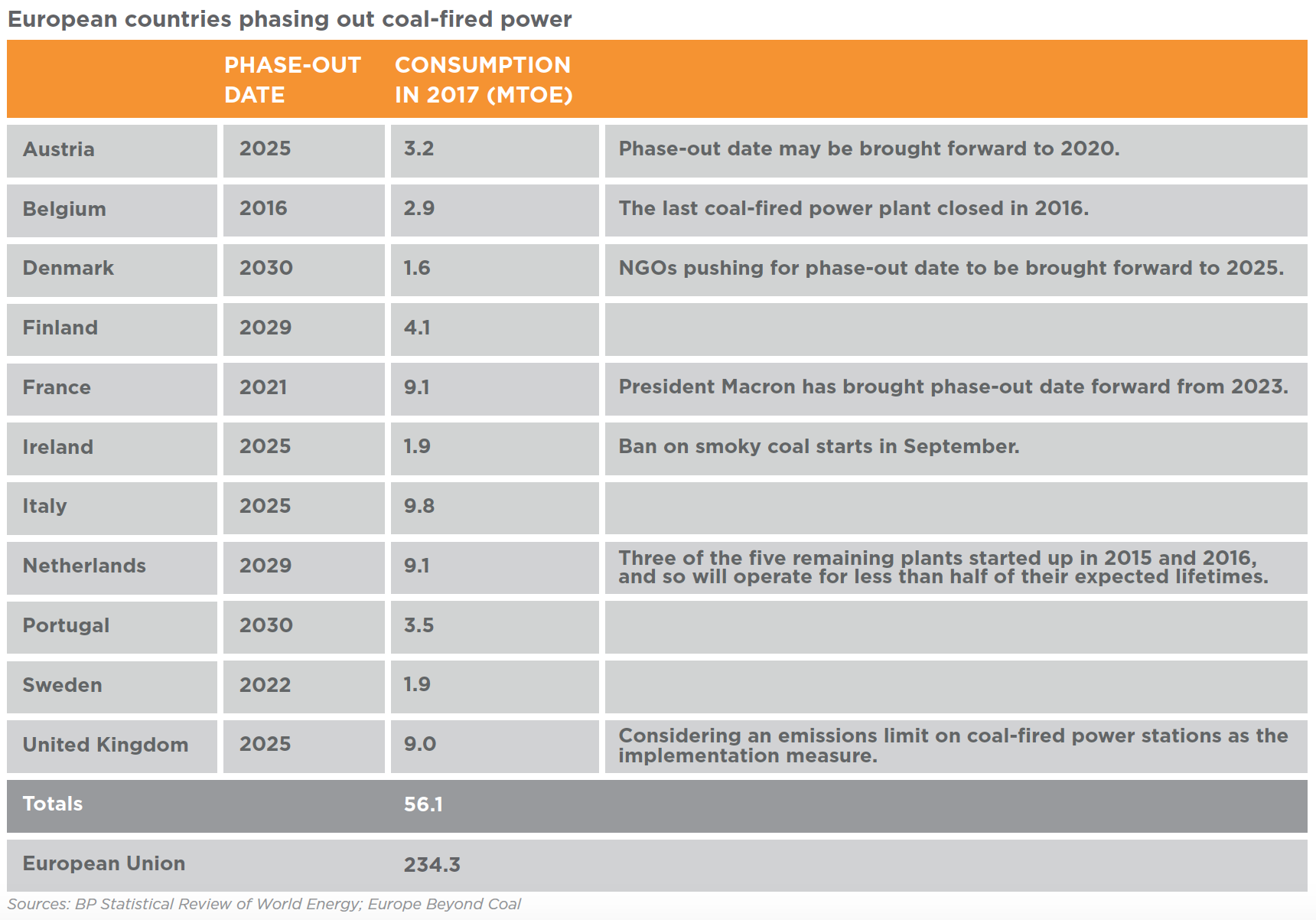

The UK thus became the first country in the world to make such a promise – starting a trend. Since then, in Europe alone, it has been joined by another ten countries, including two of the European Union's (EU) biggest economies: France and Italy.

Last November, at the COP 23 climate change talks in Bonn, the UK and Canada launched an alliance of nations, cities and states “committed to moving the world from burning coal to cleaner power sources”.

The latest European nation to join this Powering Past Coal Alliance, and to pledge a phase-out date for coal-fired power, was Ireland in March. On a visit to Toronto to meet his Canadian counterpart, the minister responsible for energy and climate action, Denis Naughten, said his country would end the burning of coal for power by 2025.

The country’s sole remaining coal-fired power station – Moneypoint, the largest generation asset in Ireland’s power system – is to be converted to burn less-polluting fuel. A final decision has yet to be made but the most likely candidate is natural gas.

Powerful symbolism

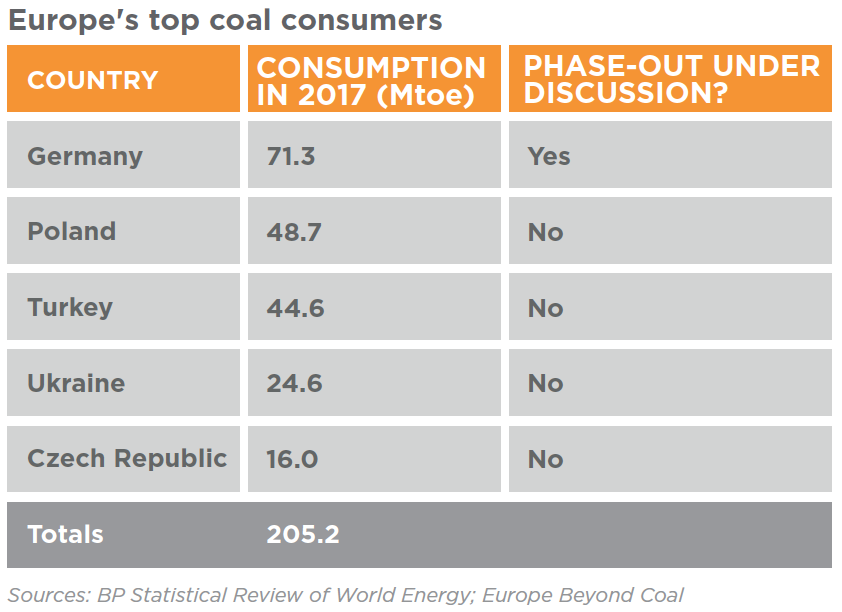

The coal phase-out promises made by these eleven European nations are largely symbolic. As the table below shows, the 11 countries that have pledged phase-outs consumed a total of 56 Mtoe of coal last year (for all uses, not just power generation).

This amounts to about a quarter of EU consumption but is less than the consumption of Europe’s biggest user: Germany. It is dwarfed by the consumption of Europe’s five biggest users, which also include Poland, Turkey, Ukraine and the Czech Republic (not all of them EU members).

The symbolism is nevertheless powerful, putting psychological pressure on those countries that have yet to make a phase-out pledge. Germany, in particular, is in the throes of a debate on what it should do next. Despite its vaunted Energiewende (energy transition), which has pushed the share of renewables in its electricity fuel mix to around one-third of the total, costing at least €25bn annually in direct subsidies alone, it is going to miss its 2020 greenhouse gas (GHG) emission target – a 40% reduction on 1990 levels.

It is a failure acknowledged by the new government in the coalition agreement signed earlier this year. Statistics from the German environment agency (UBA) show that GHG emissions in 2017 were 905mn metric tons of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e), almost the same as in 2009 and a touch higher than in 2014. Progress towards the 2020 target was just 27.7%.

The culprit is coal. Data from the federal statistical office show that in 2017, 37% of Germany’s electricity came from coal – 23% from lignite and the rest from hard coal, most of which is imported. Just 13% of electricity came from natural gas.

“In terms of climate policy that is ludicrous,” says the CEO of the German upstream oil and gas company Wintershall, Mario Mehren. “The Paris agreement does not mean less fossil fuel. Rather it means moving away from coal and using more gas. The objective of the accord is clear: it’s about achieving a significant reduction of CO2, and this reduction should be achieved without any ideological constraints, with an openness to technologies and cost efficiently.”

Merkel’s dilemma

Germany decided to phase out hard coal production over a decade ago, a process which, says the chancellor Angela Merkel, “will be completed this year.” Her dilemma is what to do about the communities that depend on lignite production. “If people were to have the impression that we were thinking only about CO2 emissions and not about the people themselves, then this would not work well as a project for society,” she said at last month’s Petersburg Climate Summit in Berlin. “This will be one of the major tasks that we intend to tackle together in this legislative term.” To that end, her government is establishing a “structural change commission” which is due to report its conclusions in December.

Under threat on many fronts

Within the EU, it is not just phase-out pledges that darken the future for coal-fired power. In anticipation of reforms to the Emissions Trading System due to take effect from 2020, the price of EU emissions allowances (EUAs) has almost tripled in recent months to around €16/tCO2 – and it would not be surprising to see prices rise further as the reforms come into effect.

A dramatic illustration of how meaningful carbon pricing can impact coal-fired power can be seen in the UK, where generators pay not only the ETS price but also a levy called Carbon Price Support.

Even before the recent rise in the price of EUAs, together they caused coal-fired power generation in the UK to fall off a cliff. When Rudd made her phase-out pledge in late 2015, coal accounted for 30% of the UK’s electricity. By July 2017 it was down to 2%. The 2025 phase-out target now looks redundant.

Yet another threat to coal-fired power comes in the form of tightening restrictions on emissions of pollutants, which present a major challenge for many of Europe’s power stations unless they are covered by transitional arrangements or derogations.

A new round of controls agreed last year by the European Commission will take effect from 2021. A report on the impact of these regulations, published by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), concludes that more than 100 power plants – representing one-third of Europe’s large-scale coal-fired power plant capacity – face costly air-quality upgrades or closure.

“The cost of compliance will be prohibitive for many of these installations, given the market outlook and other headwinds” says one of the report’s authors, Gerard Wynn.

The grid resilience challenge

As coal-fired thermal power stations close, and the proportion of renewable energy sources rises, utilities will find it ever more difficult to keep their electricity grids resilient, as Ireland has been finding. The Emerald Isle is implementing energy reforms that will see it become a world leader in the integration of renewables into an isolated grid. It is well on its way to meeting a target for 40% of its electricity to come from renewables by 2020.

But for that to be possible, the grid will need to able to handle up to 75% of variable renewable electricity at any one time (the System Non-Synchronous Penetration operational limit, or SNSP).

Keeping a large electricity network resilient is much more complex than just supplying sufficient energy. Voltage and frequency need to be kept within narrow tolerances. This requires the management of reactive power as well as active power.

Conventional power stations in which large rotating generators run synchronously are inherently more stable and thus more resilient than networks with a large proportion of non-synchronous generation. The challenge is not just about back-up energy supplies for intermittent renewables, especially in countries that do not want nuclear power – another synchronous source of generation – in their electricity mix.

Ireland, already heavily dependent on gas-fired power, therefore expects to remain dependent on natural gas generation for the foreseeable future, despite its decarbonisation ambitions. Gas and renewables are seen as complementary rather than competitors, each bringing its own set of advantages to the national electricity system. It is an imperative that Germany is just waking up to.