New IPCC head downplays 1.5°C [Gas in Transition]

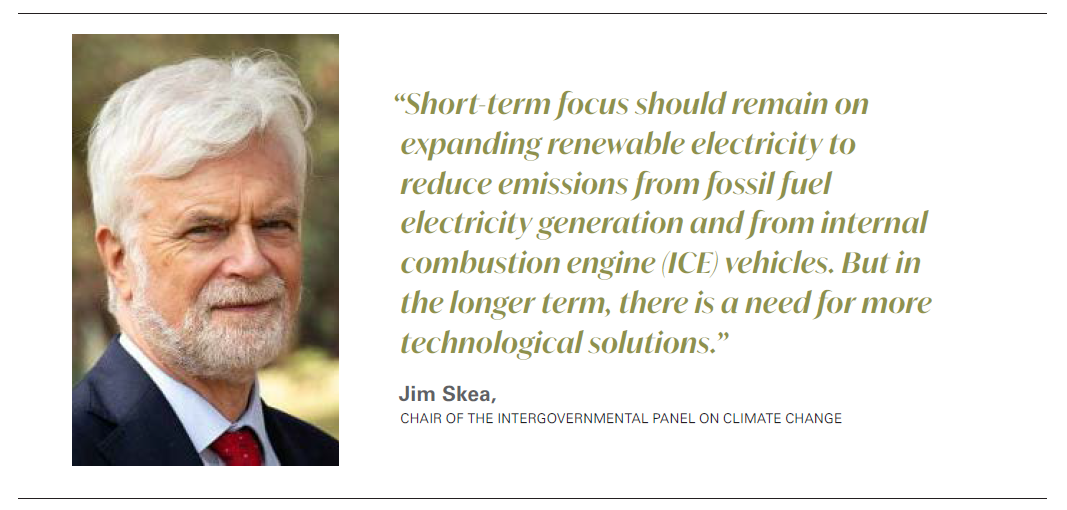

Jim Skea was elected chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in late July. He has been involved with IPCC since its foundation in the 1990s, and was previously a professor of sustainable energy at Imperial College London. His first action was to call for a balanced approach to the climate change debate, saying that “it's not helpful to imply that a temperature rise of 1.5 degrees Celsius is an existential threat to humanity.” Skea is optimistic that people still have power over the future trajectory of global warming, but “the challenges are huge.” And “the key thing is to not become paralysed into inaction by a sense of despair.”

In an interview with Der Spiegel at the end of July, Skea warned against laying too much value on the current nominal target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. He said “Don't overstate the 1.5°C threat … the world won't end if it warms by more than 1.5°C,” but it will be more dangerous.

He made these comments at a time of growing backlash against the tactics of environmental activist groups, such as Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion. He is convinced that “eco-stunts don't motivate the public to protect the planet.”

Skea is concerned that apocalyptic rhetoric risks making people apathetic and paralysed, failing to motivate them to take action. He said: “If you constantly communicate the message that we are all doomed to extinction, then that paralyses people and prevents them from taking the necessary steps to get a grip on climate change.” However, he is still worried that climate change is making the world more dangerous, but he believes that the problems “are not insurmountable.”

Skea said that short-term focus should remain on expanding renewable electricity to reduce emissions from fossil fuel electricity generation and from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. But in the longer term, there is a need for more technological solutions.

However, in its July report on the state of clean energy innovation, the International Energy Agency (IEA) warned that “there is a stark disconnect between high-profile [country] pledges and the current state of clean energy technology.” Only 25% of the cumulative CO2 emissions reductions needed to shift to a sustainable path come from technologies that have reached maturity. The remainder are still at early adoption, demonstration and prototype stages. The IEA concluded that “without a major acceleration in clean energy innovation, net-zero emissions targets will not be achievable.”

However, in its July report on the state of clean energy innovation, the International Energy Agency (IEA) warned that “there is a stark disconnect between high-profile [country] pledges and the current state of clean energy technology.” Only 25% of the cumulative CO2 emissions reductions needed to shift to a sustainable path come from technologies that have reached maturity. The remainder are still at early adoption, demonstration and prototype stages. The IEA concluded that “without a major acceleration in clean energy innovation, net-zero emissions targets will not be achievable.”

Skea does not believe that relying on people to change lifestyles alone is sufficient to “bring about the change to the extent it will be necessary." The world needs “entirely new infrastructure.” He said “we need to come down a level…it's about real people and their real lives, not scientific abstractions.” It cannot be done without “a democratic consensus on how to move, heat or eat in the future.”

He recognizes that if policymakers are to act, they need more actionable information, and fast. IPCC must improve the relevance of its policy recommendations, away from abstractions and prescriptions. With COP28 planning a Global Stocktake, through which countries will examine the emissions reductions achieved so far, what is currently planned, and what is needed to satisfy Paris goals, this is becoming quite important. In Skea’s view, the “task is to adapt to some of climate change's effects, while preventing it from getting even more severe.”

This has come at a time when the impact of global warming is becoming more pronounced through extreme climatic events, but also at a time when, as a consequence of the Ukraine war, security of energy supplies has become top priority, ahead of concerns about climate change.

What do others think?

In a recent article, the FT questioned “the scourge of climate doomism.” None of the climate scientists consulted by the FT expect “the record heat to directly trigger dramatic shifts in the global climate system,” but “might be a sign that parts of the system are losing stability.” They do not expect the earth “to become unlivable.”

And yet, in a 2021 survey of young people, the majority thought that the future is frightening and that “humanity is doomed.” Climate doomism appears to have taken over from climate denial, with the potential to cause similar damage through paralysis. People thinking that “there is nothing we can do about it,” can become a serious obstacle to tackling global warming.

For a long-time the message has been that, no matter what, temperatures will keep rising for decades to come. This belief has been reinforced by record-breaking heat-waves, fires, droughts and storms that have been devastating communities and economies throughout the world. It is not surprising that young people think the world is doomed.

There are increasing numbers of politicians, policymakers, businessmen and scientists who believe that the Paris Agreement 1.5-°C target is no longer achievable and that, in addition to trying to limit warming, countries need to prepare for a hotter world.

But, even though the risks from global warming are increasing – the world has already warmed by 1.1°C compared with pre-industrial levels – as Skea points out, the world is not at a tipping point. And acceleration in the delivery of new clean energy technologies may still get the world to net-zero and contain temperature rise.

What science says

Supporting Skea’s message, scientists have “revised their estimates of what happens if these technologies ever help us get to net zero CO₂ emissions: global temperatures would stop rising in just a few years.”

Until recently, the prevailing belief, also fed to the public, was that “a sizable amount of temperature rise is locked into the earth’s climate system,” that will keep temperatures rising for decades to come. Even if it was possible to halt all emissions now, carbon dioxide’s long lifetime in the atmosphere would keep global temperatures rising for longer than 30 years.

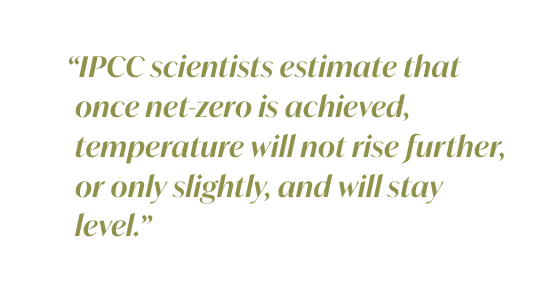

But science has shown that to be wrong. IPCC scientists estimate that, in effect, once net-zero is achieved, temperature will not rise further, or only slightly, and will stay level (see figure 1). This lag time may be limited to as little as three to five years. In other words, humanity can still limit damage if governments, businesses, and people take strong action starting now.

What figure 1 shows is if global emissions stopped now, the global temperature rise would barely change, even by 2100. Similarly, if announced country pledges are adhered to, it would be possible to limit global warming to 1.7°C this century.

Such knowledge should help “banish the sense of inevitability that paralyses people and instead inspire them towards greater resolve and activity.” Technological developments can still contribute to slashing emissions and limiting temperature rise.

This is not new science, but surprisingly it has not received the wider dissemination it deserves. Skea’s message has brought it to the fore.

Propelling action

The war in Ukraine has led to a transformation of the global energy system. As recent reports by the IEA have shown, investments in and adoption of renewables and clean energy technology, as well as energy efficiency, are accelerating, especially in Europe.

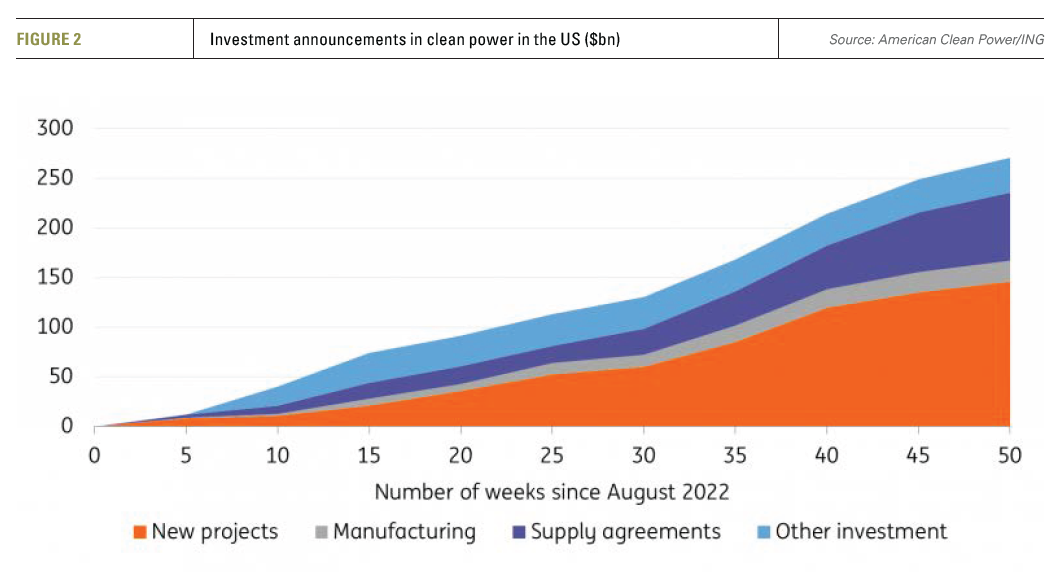

In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has spurred massive new investments in clean energy and is expected to have a profound impact on the US path to decarbonisation. Over $270bn new investments have been announced in the power sector alone since the IRA was signed into an act in August 2022 (see figure 2).

But action is not evenly spread. Investment in renewables in developing and African countries lags far behind. Africa accounts for less than 1% of the capital invested worldwide in renewables, often due to institutional weaknesses and lack of transparency.

Skea believes that “there are good reasons to be optimistic and that every measure aimed at weakening climate change helps,” recommending that in the short-term focus should remain on expanding renewable electricity to reduce emissions. He also believes these measures are becoming increasingly cost-effective. He is promoting a message of hope, rather than fear. A message that every action to reduce emissions matters.

People recognise the need to transit away from fossil fuels to clean energy. But this has to happen in an orderly manner and only as clean energy technology becomes available at scale to replace them, as the energy crises of 2021 and 2022 have shown – and events still show. That is why security of energy supplies has risen to the top of the agenda for most countries, ahead of concerns about climate change.

Energy security

With the upheaval caused by the war in Ukraine and renewables intermittency still a problem, concern about security of energy supplies has been rising. In Europe this is leading to increasing resistance to green policies in Italy, the UK, the Netherlands, Poland and even in Germany, with one of the arguments being that “it is at odds with other, more strategic, EU objectives.”

Over the last few months, the European Commission’s efforts to push climate laws have met resistance from rightwing politicians, farmers, industry and even consumers who fear that the cost of complying will be too much at a time of high inflation, industrial and economic problems. As a result, a directive on taxing heavily-polluting fuel types has been shelved, while proposals to create more sustainable food systems are unlikely to progress.

Even president Macron has called for a pause in new green legislation until existing rules are implemented. He said “we have already passed lots of environmental regulations at European level, more than other countries … now we should be implementing them, not making new changes in the rules, or we are going to lose all our [industrial] players.” He went on to say that when it comes to the regulatory side, the EU is “ahead of the Americans, the Chinese and of any other power in the world…[and] must not make new changes to the rules.”

The world needs a just, orderly and secure energy transition. With most clean energy technology still in “work-in-progress” mode, renewables comprising only 7.5% of global primary energy and intermittency still a problem, fossil fuels will be needed to support transition, preferably with coal replaced by natural gas. As Skea said, “every measure aimed at weakening climate change helps.”

The good news is that, as IPCC has pointed out, “before the Paris Agreement, the world was on track to reach 3.5°C of warming before the end of the century … since then, it is on track to reach 2.5°C. But with announced pledges from countries, it could limit warming to 1.7C, and if net-zero is reached by 2050, it could still limit warming to 1.5°C.”

It is very likely that the Global Stocktake at COP28 will retain the 1.5°C target, even if staying within it has become that much more difficult. This target has become synonymous with global action to limit climate change, and it is the basis of country and business plans to reduce emissions.

But above all, as Skea says, it is all about focusing on solutions. “I like to stay focused on the positive and the things we can actually do to address climate change, rather than getting stressed and paralysed into inaction by the fear of what’s happening.” One such positive solution would be to replace coal with natural gas within this decade.