Methane Emissions - An Existential Challenge [NGW Magazine]

It used to be mainly environmental NGOs that fretted about the oil and gas industry’s emissions of methane and their implications for climate change. Then the International Energy Agency (IEA) shone a spotlight on the problem. Now, concerned investors are insisting on greater disclosure of climate-related risks.

As the scale of the issue becomes ever more apparent, industry leaders have begun to grasp that it amounts to nothing less than an existential challenge for natural gas. The sense of urgency has become palpable. The vague good intentions of recent years have in recent months hardened into numerical targets, with firm deadlines.

Shell announced in September that it was setting a methane emissions intensity target of “below 0.2% by 2025”. In other words, less than 0.2% of the marketable natural gas the company produces will be lost to the atmosphere because of fugitive emissions, venting, or incomplete combustion in, say, flares and turbines.

Also in September, the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) set a collective 2025 target for its member companies to reduce methane emissions intensity to “below 0.25%, with the ambition to achieve 0.20%” at some unspecified time in the future. Its members are BP, Chevron, CNPC, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Occidental, Pemex, Petrobras, Repsol, Saudi Aramco, Shell and Total.

In June ExxonMobil declared it would be reducing its methane emissions by 15% by 2020, with a focus on the unconventional gas activities conducted by XTO. “It’s part of our ongoing drive to develop lower emissions energy solutions,” said CEO Darren Woods. “Since 2000, we’ve spent more than $9bn in this area.”

Clouding a bright future

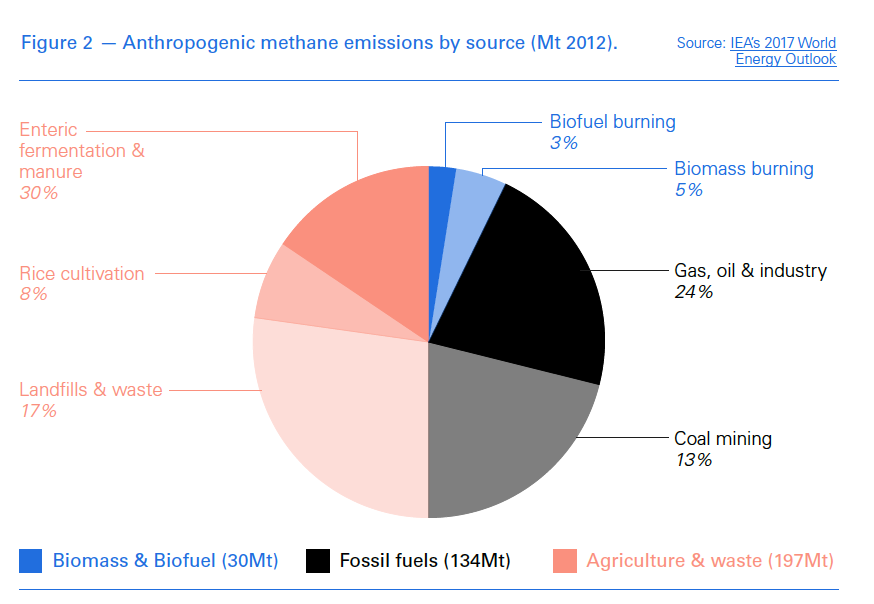

The numbers are shocking. Methane emissions are estimated to be the cause of a quarter of the warming that the planet is experiencing and 60% are anthropogenic.

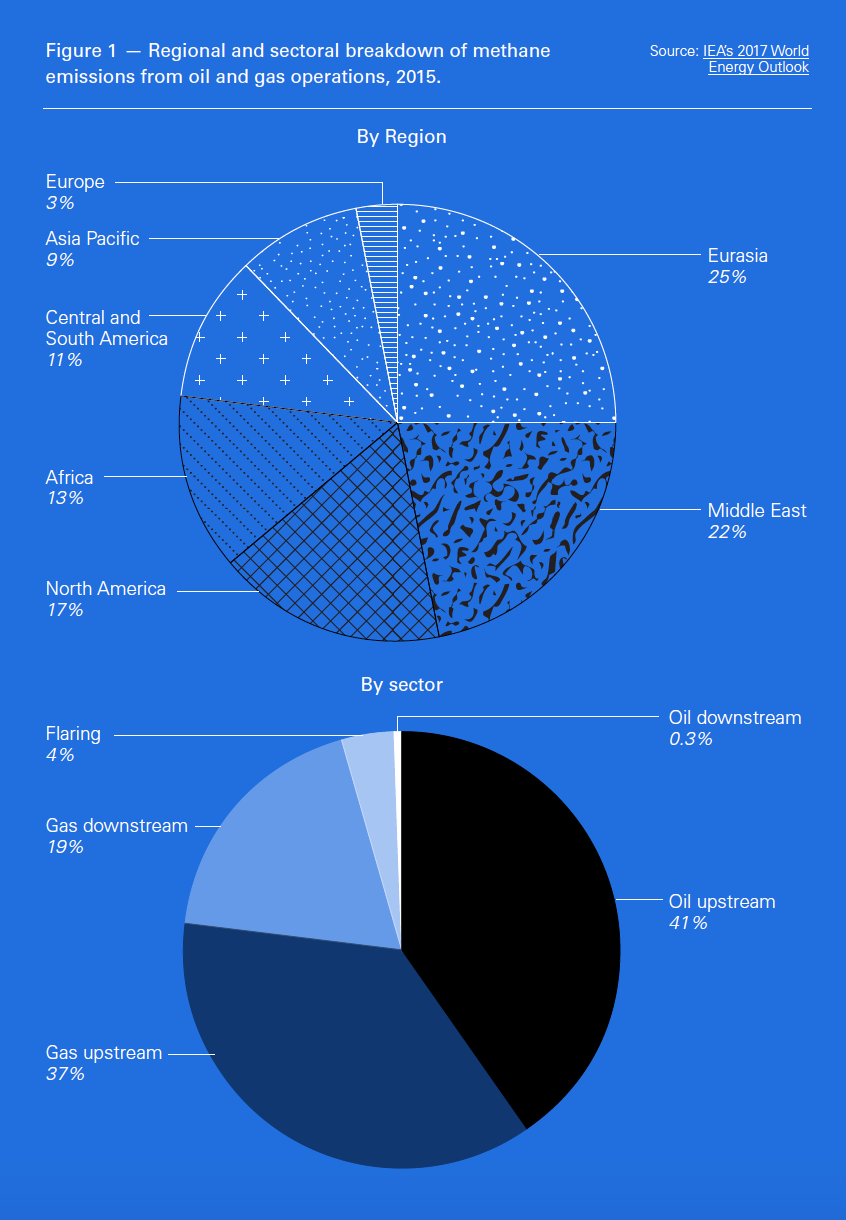

According to the IEA, methane emissions from oil and gas activities in 2015 were 76mn mt – equivalent to the LNG production of Qatar. Of this total, three-fifths were vented (released intentionally), just over a third were fugitive, while the remainder were the result of the incomplete combustion of flares.

As the chart below shows, the gas industry accounts for more than half of the total, 55%, giving an average global emission intensity of 1.7%. Little wonder that the IEA’s executive director, Fatih Birol, has been warning that methane emissions are clouding what he considers to be “a very bright future” for natural gas.

The IEA stresses that these numbers are uncertain: “Emissions levels and abatement potentials are based on sparse and sometimes conflicting data, and there is a wide divergence in estimated emissions at the global, regional and country levels.” Moreover, most published studies focus on the US.

According to the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) – a prominent US-based environmental NGO that has been playing a leading role in the methane emissions debate – the IEA numbers are probably underestimates.

A paper published earlier this year by the journal Science, co-authored by the EDF, summarised six years of field studies conducted in the US. It concluded that actual emissions from the oil and gas industry were 60% higher than the data recorded in the official government inventory.

Moreover, EDF studies conducted in Canada, Mexico and the Netherlands all concluded that field data showed higher emissions than were reported in government inventories.

“There hasn’t been a whole lot of attention paid in the industry to assessing emissions from facilities and operations,” says Mark Brownstein, senior vice-president for energy at EDF. “When you talk to folks in the industry they invariably assume that the problem is minimal.”

Global Warming Potential

Aggravating the problem is the potency of methane as a greenhouse gas (GHG).

The impact of a GHG on global warming is determined by two factors: its ability to absorb energy and the length of time it remains in the atmosphere.

Unlike carbon dioxide, which remains in the atmosphere for centuries, methane released into the atmosphere lasts for only 12 years. So, over 100 years methane has a global warming potential (GWP) of around 32 times that of carbon dioxide, while over 20 years, its GWP is around 85.

The different GWP figures lead to very different results when used to calculate global warming impacts.

There has been considerable debate over which is the most appropriate in a given set of circumstances. That said, it can be argued that the debate is less relevant than it was – because politics and practicalities have taken over, in much the same way as has happened with climate change itself.

At this year’s World Gas Conference the issue was confronted head-on by the CEOs of some of the world’s largest gas producers, among them BP’s Bob Dudley, ExxonMobil’s Darren Woods and Total’s Patrick Pouyanne.

“If we were able today, with a magic tool, to transform all the coal-fired power plants in the world into gas-fired power plants, we would be immediately on the 2 °C trajectory [in the Paris climate agreement],” said Pouyanne, highlighting the role of natural gas in the transition to lower-carbon energy world.

The industry has long insisted that gas has a crucial role to in climate change mitigation because it is less carbon intensive than oil or coal. The Achilles heel in this argument is that fugitive and other emissions of methane undermine the environmental credentials of gas, as all three CEOs acknowledged.

Given that the industry has accepted that urgent action is necessary, the question is, now what?

One answer is enshrined in a set of “guiding principles” developed by the Industry itself, international institutions, NGOs and academics and published in 2017. Signatories include the International Gas Union, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers and a growing list of producers, among them Gazprom, Qatar Petroleum and the international majors. The principles are grouped under five headings:

* continually reduce methane emissions;

* advance strong performance across gas value chains;

* improve accuracy of methane emissions data;

* advocate sound policy and regulations on methane emissions; and

* increase transparency.

The most immediate challenge is to quantify the problem. A clear message to industry, from the IEA, the EDF and industry leaders themselves is that companies should stop relying on engineering calculations and conduct field campaigns to gather data using emissions monitors and infra-red cameras. Actual mitigation need not involve a great deal of investment.

“Half of the 76n mt can be mitigated at no cost,” says the IEA’s Fatih Birol. “That would have the same impact as closing down two-thirds of all the coal-fired power stations in Asia.”

The EDF’s Brownstein points to the state of Colorado in the US, where companies are required to inspect facilities regularly. “Upwards of 80% of the emissions that were found by workers walking these sites with infra-red cameras could be fixed that day, by that worker, with a wrench.”

Methane reporting guidelines

With the oil and gas industry facing increasing pressure from investors to disclose how it is managing climate risk, last month saw the publication of guidelines to assist companies in bringing methane reporting in line with a framework established by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

The report was produced by Ceres, a sustainability NGO, the EDF, and Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), a UN-supported investor initiative.

The TCFD – formed in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board, an international body set up in wake of the financial crisis of 2008/9 to monitor the global financial system – has been developing voluntary recommendations on climate-related information that companies should disclose “to help investors, lenders and others make sound financial decisions”. It is led by Michael R. Bloomberg.

“The climate change equation is changing fast,” says EDF president Fred Krupp. “ Our new report underscores the urgent need to include methane reporting in climate risk disclosure. It provides a framework for consistent, comparable data so investors can tell which companies are positioning themselves to thrive in a carbon-constrained world.”

It is a sign of the times. Pressure from NGOs is one thing; pressure from shareholders quite another.