Gas Can Create Jobs and Growth [NGW Magazine]

Many nations recognise the need to capture more value from their oil and gas production.

Challenges range from Qatar’s relative luxury of seeking to retain its number-one position in the LNG exporters league; to Iraq’s pressing gas shortage in the power sector; and to Venezuela’s chronic problems at the other.

A new report from the International Energy Agency however says that value-adding should be an ongoing strategic priority, involving the substitution of oil burned in Mideast and other regions’ power plants with gas and renewables; shifting oil into export sales; and added-value industrial and other ventures. Its overall tenor is positive, as gas already is being monetised in many countries.

Ship out the oil

Using oil in power generation is as illogical as using Chanel to fuel your car, the IEA executive director Fatih Birol told an October 25 briefing in London to launch ‘Outlook for Producer Economies 2018’.

Exporting that oil and replacing it with gas and renewable – particularly solar photovoltaic – energy in the Middle East’s power generation business – could deliver major economic and environmental benefit to the region, the IEA’s supply chief Tim Gould told the same briefing.

Today in the Middle East about 1.8mn b/d oil is still burned for power generation, Ali al-Saffar, the IEA’s Middle East/North Africa (Mena) programme director told NGW – citing the report released in advance of the IEA’s annual World Energy Outlook which is due out November 13.

The special report focuses on six major producers – Iraq, Nigeria, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Venezuela – but examines other key resource holders such as Qatar and Turkmenistan. It finds many examples of good practice, in order to avoid the ‘preachy’ tone of some earlier IEA reports, but does not pull punches over gas flaring in Iraq, Iran and Nigeria or spendthrift Gulf countries with generous energy subsidy schemes.

Mideast gas can partner solar

Although a lot of the report deals with oil, gas nonetheless takes up much of its strategic focus.

Gas demand in Gulf Cooperation Council states has risen 2.5 times since 2000, with around half that growth coming from power generation, the report notes: “There is a strong economic case across the Middle East for faster deployment of solar photovoltaic.”

Integrating renewables into the power grid is not as big a challenge in the Mena region as in Europe, al-Saffar told NGW. This is because peaks in power demand for cooling often occur in the afternoon when solar is available. And flexibility can be provided by fast-response combined-cycle gas (CCGT) plants; in fact, 90% of power in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) already comes from CCGTs.

A reliable power supply can thus be the bedrock for industrial development.

The report also cites cases where solar power heats steam used at Omani enhanced oil recovery schemes at some fields, with the 1-GW ‘Miraah’ concentrated solar plant (CSP) under development.

Large gas-fuelled seawater desalination plants, although absorbing significant energy costs in the Mideast already, could be part of a solution for renewables integration, the report argues. If subsidies for fossil fuels are phased out, more innovative lower-carbon desalination technologies will be brought in faster across the region. As desalinated water production is forecast by the IEA to “increase almost fourteen-fold by 2040”, the imperative to switch to such greener techniques (largely powered by electricity, rather than direct burning) increases.

Investing in jobs, not subsidies

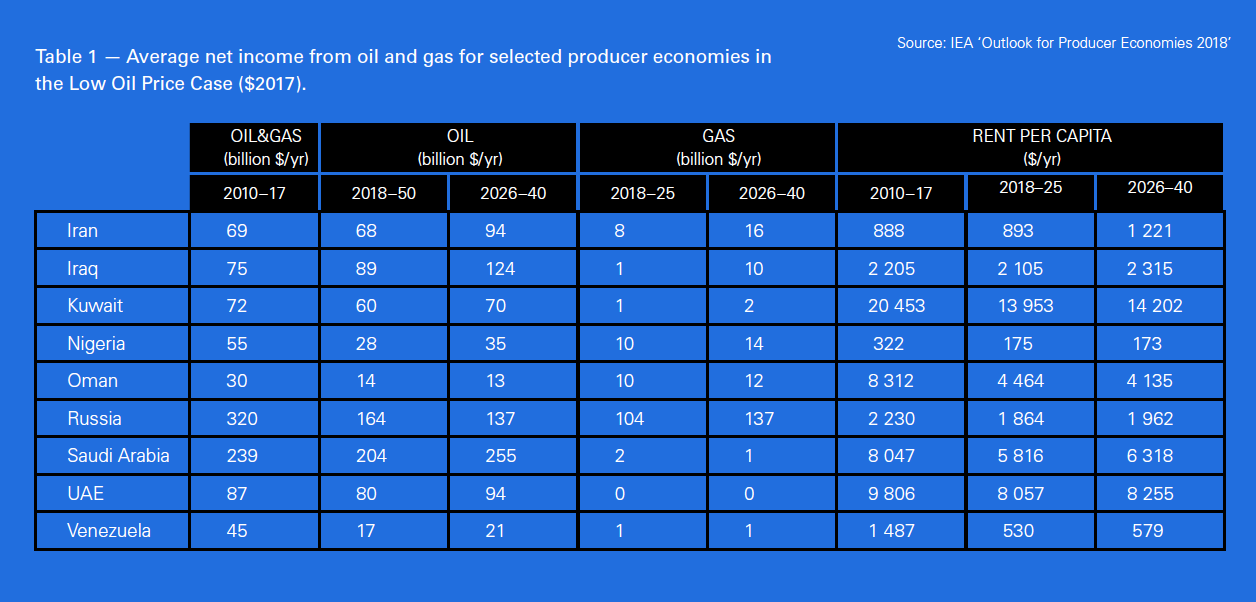

The ‘New Policies’ scenario – the report’s main and relatively benign outlook (see tables below) - assumes more use of cleaner more energy-efficient technologies over time. In contrast, the ‘Low Oil Price’ scenario is the least benign, with less cashflow available to invest in new jobs, economic diversification, and cleaner energy.

Gas can be a valuable feedstock in the petrochemical industry but, the IEA cautions, is “not labour-intensive” citing how the Qatar Petrochemical Company generates more than $1bn in annual revenues but employs just 1,000 people. So, while large petrochemical plants can act as anchor customers for smaller in-country industries, the report suggests that using gas in a wide range of industrial applications should be considered – especially given how 60% of the population in the MENA region is currently under 25 years of age.

The report moreover singles out Indonesia and Mexico as successful examples of where governments have held back from directly recycling oil revenues into non-oil industries, instead targeting revenues from oil at strategic infrastructure that can encourage foreign investment into industries ranging from textiles to tourism and even car-making.

“The youthful population in the Middle East and North Africa could bring a major boost to growth if economic opportunities are there, or become a destabilising force if they are not,” the report warns.

Pricing reform is not always simple though and the IEA cites how Saudi Arabia attracted investment from a Japanese titanium company in 2014, by offering it an electricity price 70% below what was available in Japan in 2016. UAE too is now the world’s fifth largest aluminium producer. Thus, reducing subsidies is a sensitive area for producer economies, but offering them on an agreed temporary basis can sometimes spur investment.

Iraq needs policy integration

The report identifies how several oil and gas producer states differ in their implementation of policy.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Russia all have a single entity responsible for all aspects of energy policy, and each has long-term energy planning which are periodically updated.

Strong co-ordination across different areas of energy policy is important to introduce reforms on energy efficiency, deployment of clean technologies, and in reducing energy subsidies, it notes (see sidebox on IEA’s recent analysis of the energy subsidies).

“Venezuela, Iraq and Nigeria have separate ministries for hydrocarbons and power,” the report says which “can increase the risk – present in all institutional arrangements – of misaligned policies.” In Iraq, it says, the ministry of electricity built a significant amount of CCGT capacity – but without any firm guarantee from the oil ministry that sufficient gas would be available.

Given a battle-royal for 11 GW of new Iraqi CCGT orders that will in the coming months play out between GE – with vocal backing from the US president Donald Trump – and Germany’s Siemens, NGW asked the IEA experts if CCGTs might once more be built in Iraq without guaranteed gas.

“There is an imperative for change in many of these countries; that this gas capture has to happen. This has grown out of the problems experienced in Iraq over the summer,” replied al-Saffar.

The report notes that many of the highly-efficient CCGTs recently built in Iraq now burn oil instead, some having switched back quite recently.

“These issues are well understood,” added al-Saffar and therefore he views the outlook in Iraq as “possibly quite optimistic,” given the appointment of reformist new Iraqi electricity and oil ministers on the very morning of the IEA’s report launch.

“Electricity minister Luay al-Khatteeb knows these issues extremely well; this is high up on the agenda. Likewise, we can probably expect that from the oil minister Thamir Ghadhban,” said al-Saffa. He himself was promoted within the IEA to his present post last month.

Until last month, Ghadhban had been adviser since 2016 to now former prime minister Haider al-Abadi. Al-Khatteeb has been a fellow at the Brookings Institute and New York’s Columbia University’s CGES.

Iraqi gas production is forecast to grow from 8bn m³/yr today to 115bn m³/yr by 2040, far and above the continuing strong growth in gas production elsewhere in the Middle East, the report says, while Iraqi oil production rises from 4.6mn b/d today to 5.3mn b/d in 2025 and 7mn b/d by 2040.

The report adds that Iraq has significant gas flaring today (17.8bn m³ flared in 2017, according to World Bank data) but plans to eliminate it by 2021, and that the start-up of Basrah Gas Company in early 2018 – if it eliminated flaring on its patch – could power 4.5 GW of gas-fired power. That would be enough for 3mn homes. Whether Iraq implements its target, or keeps rolling it as Nigeria has, remains unclear.

Even Qatar faces structural change

All oil and gas producer nations face three new structural pressures, said Birol – first from the shale revolution (more than half of global oil growth to 2040 will be shale, chiefly from the US); second on the demand side, with less road fuel likely to be needed per car to move it the same distance; and third on the climate change agenda.

Asked if he was confident that Qatar will achieve its recently upward revised target of 110mn mt/yr LNG production by around the mid-2020s, from 77mn mt/yr today, IEA chief Birol’s reply was nuanced.

“Qatar has been the undisputed leader of LNG. But in the mid-2020s there will be three in the champions league - US, Australia and Qatar – with three different business models in terms of contract length, funding, and flexibilities. Life for Qatar and others will be different in the future. There will be more competition even in the context of LNG. But Qatar is definitely an important country here and will continue to be so: it has a lot of advantage from the [feed gas] production through to shipping, and from its excellent relationships with clients.”

Turkmenistan’s options bleaker

Russia is pursuing a strategy to access new markets, both through pipelines to China but also through the optionality you get from LNG, said IEA supply chief Tim Gould.

He said the report looked at how three major gas resource holders – Russia, Qatar and Turkmenistan – may have choices shaped by not only by changes in the gas market but also by geography: “Qatar is clearly favourably positioned to react quickly to changes in market from its geographic position between Europe and Asia; Russia is increasingly moving in that direction.”

Turkmenistan’s options though are less open, admitted Gould: “There’s been some discussion about resuming larger exports through Russia, as the country is heavily dependent on that eastern route [to China] and some modest exports to Iran. But the prospect of opening up a major new pipeline route either west [under the Caspian] or south [as TAPI, to India] has massive political complexities. And as LNG has increased its role in international gas trade, so we have become slightly more pessimistic about some of the gas that is in the middle of Eurasia, and how that is going to be reaching markets at a time when people are demanding that flexibility and optionality.” That pessimism now seems justified, with Azerbaijan saying late October it will stop importing Turkmen gas in January 2019 as it has enough gas of its own.

Few if any countries featured in the report escape criticism on some aspect or other. Saudi Arabia drew nearly $240bn from its reserves to plug a large budget deficit between 2014 and 2017 created by lower oil export revenues, little of which went on long-term strategic infrastructure investment.

Nigeria saw oil and gas investment fall by almost half between 2010 and 2017, while oil production fell by 25% since 2012 to about 2mn b/d in 2017. Yet uncertainty over its Petroleum Industry Bill (with elections due in February) has deterred new investment, dampening IEA forecasts for Nigerian output in the early 2020s. Oil and gas account for over half of Nigerian government revenue.

And the report devotes a whole page to what it might take to turn Venezuela’s production around – but admits it would require a political and economic “sea-change” to bring investment back, forecasting that upstream output will “bottom out in the mid-2020s” before any gradual recovery.

Outlook is positive, when gas has value

Yet despite some bleak spots, Gould sees that gas in many regions has a marketable value that it didn’t have before – though this is still truer in the Middle East than in Angola or Venezuela.

“The debate about gas has changed quite substantially in recent years. For a while, it was available at low cost as associated gas,” said Gould: “Now that marginal cubic metre either has to be imported or produced locally, and that creates a whole different dynamic around gas pricing in many parts of the [Mideast] region. In the UAE for many years, you had natural gas prices at the equivalent of $1/mn Btu. Currently that’s north of $3. And they are orienting around an expectation that they will be somewhere around $5 in the not too distant future.

“When natural gas is already at $5/mn Btu, you have a different debate domestically about where you get the best value from gas. It is already not a cheap by-product available from oil production, it is something you need to value,” added Gould.

“If you look at our supply numbers for the Middle East, one of the big items is the reduction of crude being burned, and that is obviously a product of displacing oil [from power generation] with gas and renewables. In Iraq, we worked very closely with the expansion of gas gathering capacity in the southern fields, and what that does to the domestic energy mix, and for expanding output.”

Subsidies bouncing back: IEA

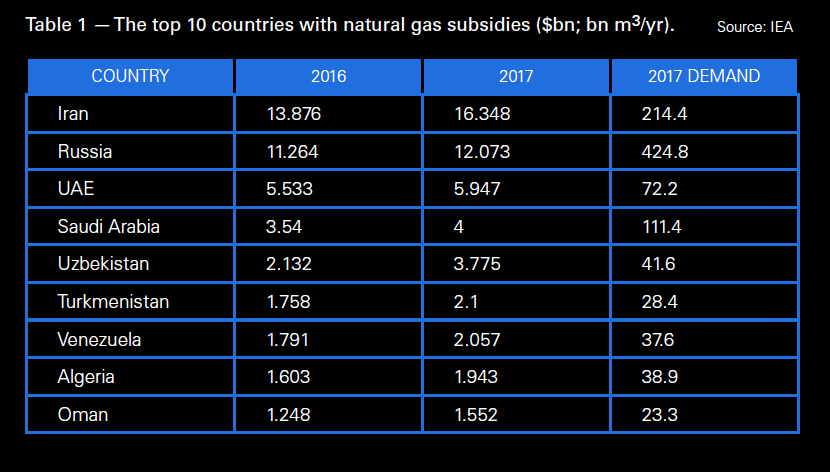

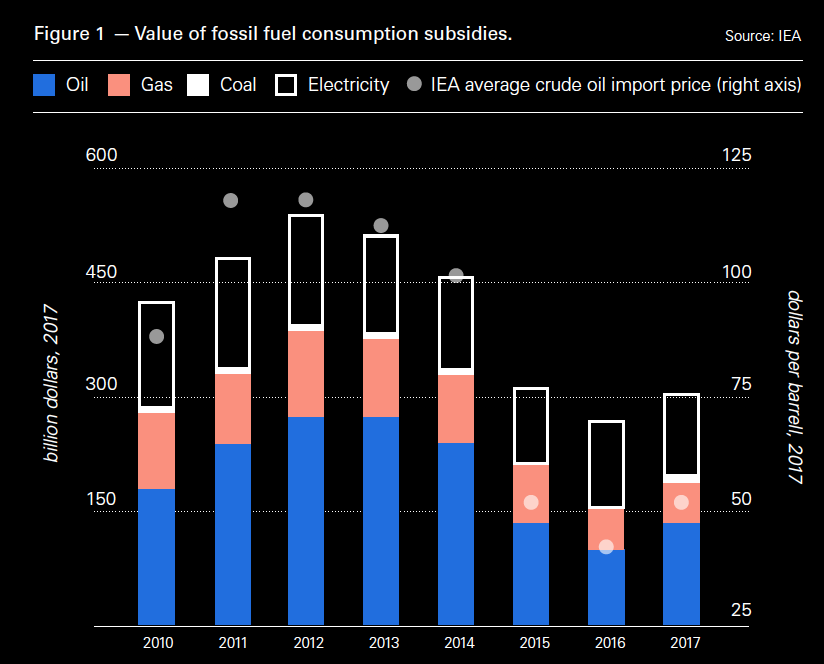

The IEA said global oil, gas and fossil-fuelled electricity consumption subsidies almost halved between 2012 and 2016, down from the peak, reached in 2012, of over half a trillion dollars. However, the value rose again by 12% year-on-year in 2017 to around $300bn, owing to a 30% rise in oil prices, plus an 18% ($56.64bn) year-on-year rise in gas subsides.

Iran ranked first last year at $45bn, outpacing China. Iran's 2017 total includes $16bn in natural gas subsidies; Russia came second at $12bn. The report, published October 19 says that most of the increases relate to oil products, reflecting higher prices which, if there is no change in an artificially low end-user price, increases the estimated value of the subsidy.

Regarding rising oil prices this year (33% up on average in the first three quarters) it appears that subsidies are likely to increase again in 2018. The IEA said that 2018's rising oil prices are putting pricing reforms under pressure in some countries.

The majority of those governments burdened by heavy subsidies also suffer from gas flaring. Cutting subsidiaries can, however, help them to invest in both enhancing efficiency and a reduction in gas flaring.

According to the World Bank-led Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR), flaring declined to 140.6bn m3 in 2017, down by 4.7% from the 147.6bn m3 seen in 2016. However, Russia, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Nigeria and other hydrocarbon-rich countries with huge subsidiaries remain at the top of this list of flarers.

The IEA said that many subsidies are poorly targeted and disproportionally benefit those wealthier segments of the population that use more subsidised fuel. It stated: “Such untargeted subsidy policies encourage wasteful consumption, pushing up emissions and straining government budgets. Phasing out fossil fuel consumption subsidies is a pillar of sound energy policy.”

The report states that high oil prices in the 2010-2014 period provided strong motivation for many oil-importing countries to pursue subsidy reform, adding that the subsequent fall in prices that began in 2014 presented an opportunity. A number of countries, including India, Indonesia, Mexico and Malaysia have, since then, implemented pricing reforms.

These reforms have also gained ground among fossil fuel exporters. In many cases subsidies represent a cost in the form of lost revenue, rather than an explicit financial burden, but the straitened circumstances of many oil and gas exporters in recent years have provided an impetus to make changes in their energy pricing; Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have all increased their domestic prices for gasoline, natural gas and electricity.

The IEA predicts that the rise in international fuel prices in 2018 could, however, set back efforts to phase out fossil fuel subsidies. Consumers in many oil-importing countries are facing a hike in retail prices, particularly in those developing economies that have currencies that are depreciating against the US dollar. The 75% rise in the dollar-denominated Brent crude price since January 2018 translates into a greater than 100% rise when realised in Indian rupees, and a 250% increase when priced in Argentinian pesos.

Given these pressures some countries have started pushing back their reform schedules by postponing price rises, or by otherwise protecting consumers from their efforts, while in most cases keeping the overall policy of market-based pricing in place. For example, despite higher international prices, Indonesia and Malaysia have kept domestic prices at previous levels, while India has cut the excise duty on gasoline and diesel, and Brazil has increased its subsidy on diesel.

These price controls can shield consumers from short-term changes in international market prices but come with a fiscal and environmental cost. Moreover, they diminish the potential for higher prices to curb demand and bring the market back into balance.