LNG bunkering: some pros and cons [NGW MAGAZINE]

The shipping industry is going through its biggest fuel transition since moving from coal to oil in the early 1900s, ahead of stricter international rules on emissions coming into force next year. While oil-based products will continue to dominate the marine fuel market for decades to come, new caps on emissions also provide a greater opening for LNG.

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) requires that vessels worldwide reduce the sulphur content of their fuels to 0.5% from January 1, compared with a current limit of 3.5%. Shipowners have several options for complying with this legislation. Many are investing in scrubbers, which strip sulphur particles from ships’ exhaust smoke. Others are switching from high-sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) to cleaner lower-sulphur fuel oil (LSFO), gas oil and LNG, with Wood Mackenzie projecting that global demand for HSFO will shrink from 3.5mn b/day to just 600,000 b/day next year.

LNG is by far the best option for marine transport, its advocates argue. First, there are its green credentials – not only does it release 99% less SOx emissions compared with HSFO, easily clearing IMO standards, but it also emits 80% less NOx, 25% less CO2 and 99% fewer fine particles. Proponents of LNG such as Finland’s Gasum, also insist that it is cost-competitive. The company carries out truck-to-ship, terminal-to-ship and ship-to-ship LNG refuelling in Finland, Sweden and Norway, operating one specialised bunkering vessel and another with bunkering capabilities.

“We talk to shipowners on a regular basis and they tell us how they are saving money with LNG,” Gasum’s vice president for natural gas and LNG, Kimmo Rahkamo, told NGW.

Past forecasts for the growth in LNG bunkering have disappointed. Sergei Jefimov, head of LNG supply and logistics at Estonia’s Eesti Gaas, blames this on the slump in fuel prices that followed the 2014 oil price crash.

“The cost case for LNG is now much better than it was a few years ago,” he told NGW.

Eesti Gaas carries out bunkering in the Finnish ports of Helsinki and Hanko, and Tallinn in Estonia. Its main customer is a sister company called Tallink, which runs a passenger line between Estonia and Finland.

“[Low fuel prices] were a part of it, but I think the biggest factor is that shipping is a very conservative industry and going into something new takes time,” Rahkamo told NGW.

Times are changing, however. IMO rules are encouraging more shipowners to look at LNG seriously, as is consumer pressure on companies to reduce the overall carbon footprint of their activities.

“We are seeing more and more ships coming into the market; the pace is clearly increasing. It is now a global phenomenon rather than just happening in certain regions,” Rahkamo said. “There are frontrunners; shippers realising that the supply is there and the price is reasonable, so why not. And when others see their competitors getting cheaper fuel and reducing their emissions, they want to follow a similar path.”

Industry executives who spoke with NGW said passenger ships, such as ferries and larger-sized cruise ships, represented one of the biggest opportunities in the market at present. “But there are big opportunities everywhere, in cargo ships, container ships, ferries,” Jefimov said.

Executives were generally downbeat on the opportunities in retrofitting existing vessels to run on LNG, however, with growth expected to be confined mostly to newbuilds. “I’m not a great believer in these retrofits, especially in cargo vessels because they take up storage space,” Rahkamo said, referring to the lower energy intensity of LNG relative to conventional fuels. For existing vessels, especially older models, investing in scrubbers represents a cheaper and more convenient option.

The consensus is that there is more than enough capacity in terms of LNG production and infrastructure to support growing demand for bunkering. But a key challenge is geographical coverage. While some areas, such as Scandinavia, have spent years developing bunkering infrastructure, some regions such as the Asia-Pacific zone are only just getting started.

“This is not a problem if a ship routinely goes between two different ports only, but if a ship goes everywhere in the world, then the LNG bunkering infrastructure needs to be everywhere,” Rahkamo said. Pioneering the development of worldwide infrastructure are global players such as Shell and other majors. This benefits smaller players as well.

Unintended consequences

Authorities – not only national and supranational governments, but also port authorities – also need to do more to support the sector. Some ports need to introduce lower fees for LNG-fuelled ships based on their cleaner emissions, industry executives say; while others need to do away with restrictions and other detrimental policies.

A case in point in Norway, which despite being a frontrunner in the development of LNG bunkering, applied a CO2 tax last year on LNG, which previously enjoyed an exemption. Industry groups quickly warned that the policy, designed to curb emissions, might have the opposite effect, reducing the incentive for shipowners to use LNG instead of dirtier fuels.

Projections for future demand for LNG bunkering vary significantly, potentially weighing down on investment in supply and infrastructure. Qatar Petroleum, which recently partnered with Shell to develop LNG bunkering, sees consumption reaching 35mn mt/yr by 2035. Meanwhile Lloyds Register suggests a growth to 45mn mt/yr by this point and 65mn t/yr by 2040.

Still, LNG’s share of marine fuel is unlikely to exceed much more than 10% by 2030, according to Edinburgh-based consultancy Gneiss Energy, though this still represents substantial growth from the current 0.3%.

“In preparation for IMO 2020, a lot of talk has focused on LNG bunkering and quite rightly so,” Gneiss expert Ian Simm told NGW. But despite the positive rhetoric and the cost benefits LNG offers, low-sulphur fuel oil (LSFO) will retain the lion’s share of the marine fuel market, he said.

“The strong appetite for LSFO is a significant impediment to the growth of LNG bunkering as this fuel can be used without converting vessels to run on LNG,” Simm told NGW. “The gap that bunkerers will be targeting is created by the uncertainty caused by a lack of LSFO supply, particularly in Asia.”

High-sulphur fuel oil accounts for 55% of the fuel market and medium-sulphur fuel oil has 20%.

|

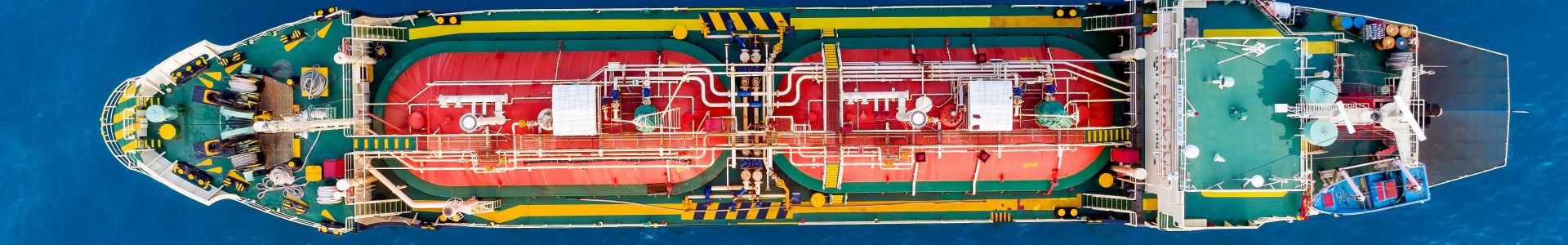

Total joins the LNG bunkers The French major Total has joined Anglo-Dutch Shell as an international oil company in the LNG bunkering services business. The two companies are the second biggest and biggest privately owned LNG traders by equity offtake volume, and are looking for new markets for their product. Total has now launched its first large vessel, following the signature of a long-term charter contract between Total and Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL) in February 2018, it said October 18. After delivery in 2020, the bunker vessel will operate in northern Europe, where it will supply LNG to commercial vessels, including 300,000 metric tons/year for CMA CGM’s nine ultra-large newbuild containerships in Europe-Asia trade, for at least 10 years. The LNG bunker vessel’s construction is in line with the IMO decision to drastically limit the sulphur content of marine fuels next year. In this context, the transition from heavy fuel oil to LNG is a competitive, efficient and immediately available solution for maritime transportation, Total said. “Developing infrastructure like this giant bunker vessel is essential to allow LNG to become a widely used marine fuel,” said Total. “This first ship demonstrates our commitment to offering our customers both more environmentally friendly fuels and the associated logistics.” Built by Hudong-Zhonghua Shipbuilding near Shanghai, the bunker vessel is fitted with innovative tank technologies, with a capacity of 18,600m³, provided by the French company GTT. Designed to be highly manoeuvrable, the 135-metre vessel will be able to operate safely in the ports and terminals considered. The vessel also uses LNG as fuel and can completely reliquefy boil-off gas. CMA CGM launched the “world’s largest” 23,000 x 20-ft equivalent units (teu) LNG-powered containership at Shanghai Jiangnan-Changxing Shipyard September 25. The vessel named Jacques Saade will also be equipped with a smart system to manage ventilation for the reefer containers carried in the hold, the company said. One teu is 20 ft long by 8 ft wide by 8.5 ft high. In 2017, the company announced its decision to order nine such containerships. |