Libya kicks off major gas project [Gas in Transition]

Eni and Libya’s National Oil Company (NOC) agreed on January 28 to develop “Structures A&E” – a strategic project to increase gas production to supply the Libyan domestic market as well as exports to Europe.

The agreement was signed by Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi and NOC CEO Farhat Bengdara, in the presence of the prime minister of Italy, Giorgia Meloni, and the prime minister of the internationally-recognized Libyan Government of National Unity (GNU), Abdul Hamid Al-Dbeibah.

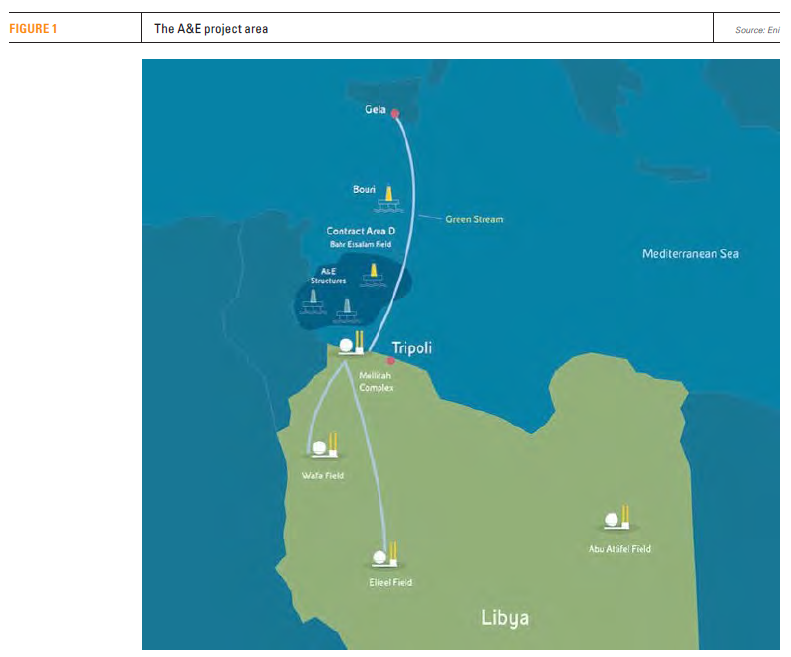

This is the first major project in Libya since about 2000. It will involve the development of two gas fields, A and E, located in the contractual area D, offshore western Libya (see figure 1), with combined gas reserves of about 6 trillion ft3. According to Eni, production will start in 2026 and will reach a plateau of 750mn ft3/d. The agreement is for 25 years.

The project will involve two main production platforms tied to the existing treatment facilities at Eni’s Mellitah complex. It will also include the construction of a CCS facility at Mellitah, allowing a significant reduction of the project’s overall carbon footprint, in line with Eni’s decarbonisation strategy. The overall investment is estimated to be about $8bn, and it is expected to make a significant contribution to the Libyan economy. Meloni said Italy wants to help African nations “grow and become richer”, adding that "it is clear that Libya is a strategic economic partner for us." She described the deal as "big and historic" and added that it would help Europe secure energy sources.

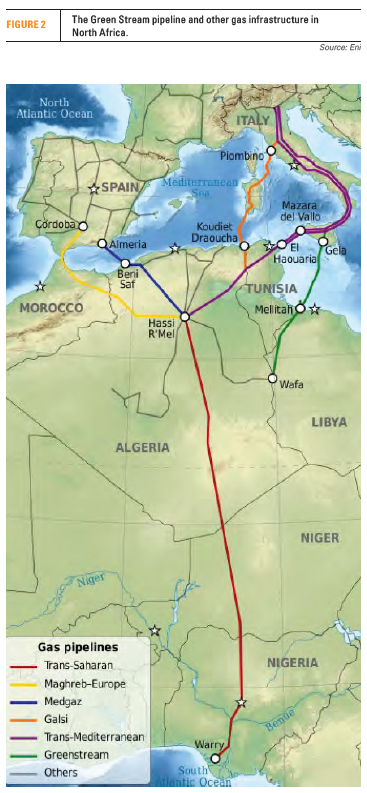

These projects form part of Eni’s efforts to ensure more secure gas supplies to Italy, as part of the country’s drive to replace Russian gas. The importance Italy attaches to this is evident by the presence of Meloni at the agreement signing ceremony. These efforts also include sourcing new gas from Algeria and Egypt.

Eni operates another two gas fields in Libya: Wafa and Essalam. In mid-December, the Mellitah Oil & Gas company, jointly owned by Eni and NOC, reopened four wells in the Bahr Essalam offshore gas field, increasing gas production to about 80mn ft3/d.

The gas is transported from Mellitah to Sicily through the 540km Green Stream pipeline (see figure 2) that has a capacity of 8bn m3/yr. In fact, Eni is the leading gas producer in Libya with an 80% share of the country’s gas production.

Gas exports to Italy through this pipeline reached 2.63bn m3 in 2022, well below its capacity and well below the level of gas exports before the 2011 crisis.

Eni has also been discussing renewable-related projects in Libya.

Libya’s gas potential

Libya has the 5th largest combined oil and gas reserves in Africa. Its proximity to Europe potentially makes it a key gas supplier to the EU. In 2021, oil revenues accounted for an estimated 98% of Libya’s total government revenues, according to Libya’s Central Bank, making it the country’s lifeline.

Most of Libya remains underexplored, but ongoing civil unrest is making a large-scale exploration programme difficult, except perhaps offshore – where Eni is now focusing its new interests.

Bengdara estimates that Libya’s proven gas reserves total 80tn ft3. He said that the country is now focusing on boosting gas production for export to Europe.

In addition to the A&E project, Bengdara said that Eni and BP plan to start offshore drilling soon. NOC is also in talks with TotalEnergies to increase production and investment in Libya, especially at the Waha concessions where there is potential to expand oil production considerably.

Bengdara added that NOC is ready to offer new concessions “to those who are ready to meet our fiscal regimes." He has an ambitious aim to increase oil production capacity to 3mn barrels/day from about 1.2mn b/d now.

In support of this, NOC announced a new ‘transformational’ strategic plan for its oil and gas sector, after contracting global management consulting firm Kearney to help develop it. NOC is creating a Strategic Programs Office, which will be responsible for implementing this plan and other initiatives, projects and programs, which will “contribute to the transformation of the oil and gas sector in Libya and ensure it keeps pace with developments in this sector worldwide.”

NOC said that it now expects to sign more deals with international companies following the agreement with Eni. Bengdara went as far as to say that the deal sends “a clear message to the international business community that the Libyan state has passed the stage of political risks.”

But continuing and persisting political chaos may challenge that.

Challenges

Governmental control in Libya is fractured, with centres of power at Tripoli, led by GNU, and at Sirte in the east, led by Fathi Bashagha, who is supported by Libya’s parliament based in Tobruk. And if that is not enough, General Khalifa Haftar controls Cyrenaica. The many rivalries and conflicts between them risk thwarting efforts to develop the country’s energy potential.

Armed factions aligned to the various sides frequently resort to warfare. However, since fighting in 2020, the oil and gas sector has been relatively stable, enabling force majeure on oil and gas exploration activities to be lifted in December.

This was confirmed by Bengdara when he said “most of the oil-service companies have returned to the fields, and the security situation is stable in the fields.”

However, attempts by the international community to convince the various sides to hold a new general election have so far failed leaving the country in political limbo. The potential for further unrest remains.

As a result, despite Bengdara’s assertions and optimism, the country still faces challenges in kick-starting new oil and gas developments due to its ongoing internal conflict that has divided the country even since the overthrow of Qaddafi in 2011.

Underscoring this, Libya’s oil minister, Mohamed Oun, even though a member of the GNU government, rejected any deal that NOC might strike with Italy, saying that such agreements can only be made by the ministry. He went as far as to say that the agreement completely violates the law, calling it illegal. He called on the head of NOC “to follow the legal mechanisms and refer the technical and economic justifications for concluding the deal to the ministry of oil.” This standoff may, in part, be related to the fact that Bengdara is said to be close to General Haftar.

The deal may even be challenged by Libya’s eastern-based parliament that no longer recognises the GNU because, it says, its mandate has expired.

Meloni called for a “broad national political compromise to help unblock the current stalemate,” but so far this is falling on deaf ears.

In addition to the standoff between the GNU and the parliament, Libya’s appeals court has suspended the maritime and energy exploration deal struck between Libya and Turkey last year.

And in another twist, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi proceeded with a unilateral declaration of Egypt’s maritime border with Libya mid-December, despite protests from Libya.

Nevertheless, despite these risks and challenges, Eni and TotalEnergies look set to continue their efforts to expand their commitments and investments in Libya.