Italy would profit from new LNG import terminals [Gas in Transition]

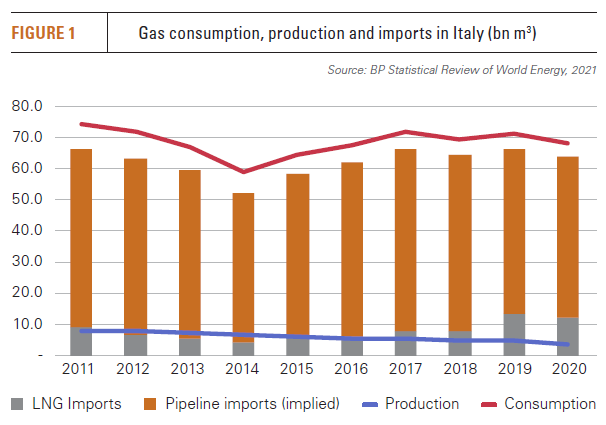

Italian LNG imports saw a high of 13.5bn m3 in 2019 and, despite the impact of the coronavirus, which hit the country particularly hard, remained elevated in 2020 at 12.1bn m3. The drop in LNG import levels last year, 1.4bn m3, was relatively small considering that consumption fell by 3.1bn m3 and domestic production was 0.7bn m3 lower at just 3.9bn m3 (Figure 1).

LNG imports met 17.8% of Italian gas demand last year, down from 19.0% in 2019, but still the second highest level on record.

Arrested development

Italy was an early starter on the LNG scene, being only the fourth country in the world to build an LNG terminal, Panigaglia LNG, which came onstream in 1971 with capacity of 2.5mn mt/yr. This allowed it to import short haul LNG from Libya’s Marsa El Brega LNG plant, which started up in 1970.

However, it took until 2009 for the country’s second import terminal, Adriatic LNG, to be completed. The terminal has capacity of 5.8mn mt/yr. Italy’s third facility, Toscana FSRU, followed four years later, adding a further 2.7mn mt/yr, bringing the country total to over 11mn mt/yr (15bn m3).

For the last two years, Italy’s LNG import terminals have been operating at high levels, a development reflecting the introduction of an auction-based allocation mechanism in April 2018. According to International Gas Union data, utilisation last year was 82%, second only in Europe to Belgium’s 90% and much higher than countries like France (66%), Spain (37%) or the UK (38%).

Italian regasification capacity as a proportion of overall gas consumption is, in fact, low – 22.1%, in comparison with 33.4% for the Netherlands, 71.5% in the UK and 83.5% in France.

Individual market characteristics

Europe’s gas systems nationally have very different characteristics, so Italy’s limited LNG import capacity in relation to overall consumption is not necessarily a weakness. Germany, the EU’s largest consumer of gas, for example, has yet to build its first LNG terminal, finding supply security in multiple import pipeline connections and large gas storage volumes.

Italy, too, relies on large working gas storage capacity, second only to Germany in the EU, and diverse pipeline connectivity, which has been further enhanced by the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which came on stream last year.

In contrast, the UK has a large amount of LNG import capacity relative to overall demand and diverse pipeline connections, but exceptionally small storage capacity. Following the closure in 2017 of the Rough facility, the UK had just 1.5bn m3 of working gas storage versus total consumption of 79.5bn m3. Little has been added since.

In comparison, Italian storage capacity at the time was 18.4bn m3 and Germany’s 24bn m3.

A key difference with both Germany and Italy is that UK domestic gas production remains relatively high at 39.5bn m3 in 2020, equivalent to 54.5% of total consumption. In contrast, German domestic gas production accounted for just 5.2% of consumption, while the ratio for Italy was 5.8%. Both Italy and Germany are thus much more dependent on gas imports.

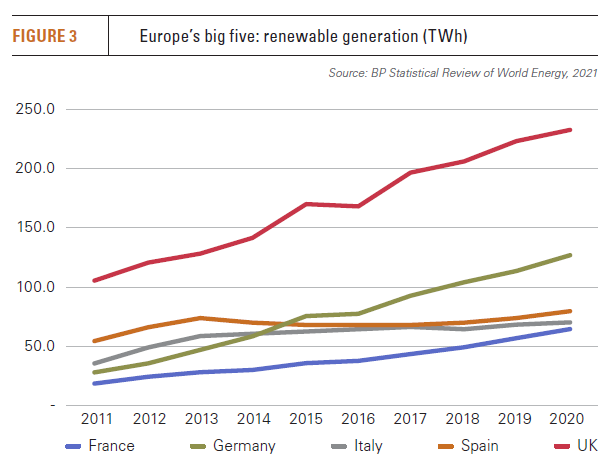

However, the UK and Germany’s generation mixes are far more diverse than Italy’s, despite a rapid coal phase-out in the former and a nuclear phase-out in the latter. Germany intends to retain coal-fired generation into the 2030s, while the UK will have some, although most likely much reduced, nuclear capacity, owing to the construction of the Hinkley Point C reactor and possibly other new reactors. In addition, both have invested substantially more than Italy in renewable energy capacity.

Italy is unique in that it combines a very high dependency on gas with a very low proportion of overall gas consumption that can be met through LNG imports.

Limited diversification

Across Europe, fossil fuel generation is coming under pressure from growing renewables output. Broadly, gas-fired generation is surviving as coal-fired generation is phased out via regulatory decisions, and, economically, by much higher carbon prices, following reforms to the EU emissions trading scheme introduced in 2018.

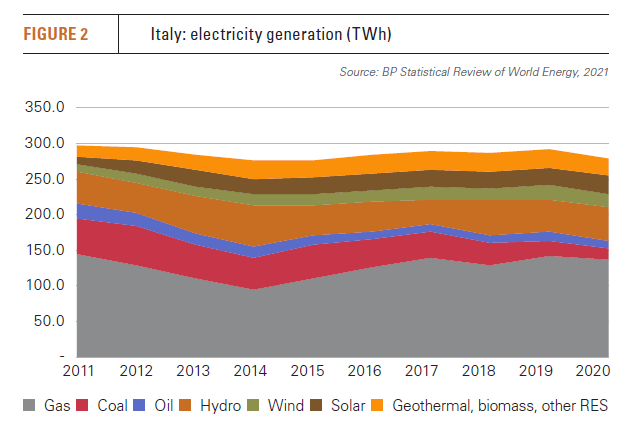

In terms of phasing out coal, Italy is no exception. A decision was taken in 2017 to end coal-fired power by 2025. Last year, coal generation fell to 16.7 TWh, down from 21.3 TWh in 2019 and a high of 54.1 TWh as recently as 2012. This is a slower decline than countries with similar or higher former levels of coal-for-power use, for example the UK and Spain, both of which have reduced coal-fired generation to minimal levels well ahead of coal phase-out deadlines.

Nonetheless, it seems likely that Italy’s remaining eight coal plants, already operating at low levels (Figure 2), will end all generation by the phase-out deadline.

However, when it comes to renewables, Italy is an exception. Compared with Europe’s other G7 economies – France, Germany and the UK – Italy is a laggard (Figure 3). Despite an early boom, solar capacity in Italy has increased in only relatively small increments since 2013, while wind has been similarly sluggish. Comparing 2016 with 2020, Italian renewable energy generation has increased by just 7.2%, in comparison with 64.3% in France, 64.6% in the UK and 37.4% in Germany.

While Rome has ambitious stated goals for renewable energy, the mechanisms to incentivise deployment are not working. Under the country’s RES1 decree, an auction held in June for up to 1.48 GW of new renewable energy projects attracted bids of just 98.9 MW, of which a mere 73 MW were awarded. The RES1 system originally aimed to incentivise 8 GW of capacity by 2023/24.

While Rome has ambitious stated goals for renewable energy, the mechanisms to incentivise deployment are not working. Under the country’s RES1 decree, an auction held in June for up to 1.48 GW of new renewable energy projects attracted bids of just 98.9 MW, of which a mere 73 MW were awarded. The RES1 system originally aimed to incentivise 8 GW of capacity by 2023/24.

Developers are waiting for the RES2 regime, which will follow two further RES1 auctions, but the broader problem is not so much the auction structure or incentives but excessive bureaucracy, which results in slow permitting and decision-making processes at all levels of government.

This is also holding back offshore wind development. While northern Europe is enjoying a surge in offshore wind investment, Italy has only one near shore 30-MW wind farm under construction, its first. As a result, sharp rises in renewable energy capacities and output look unlikely over the next five years, which will keep the country’s dependence on gas high as coal generation declines.

High-priced market

Amid unusually strong summer pricing for LNG, driven primarily by Asian demand, Italy’s LNG import levels have fallen this year as suppliers stepped up pipeline imports.

According to data from price reporting agency Argus, Italy received 108 LNG cargoes between October 2020 and June 2021 and sent out 30.5mn m3/d into the national gas system. This made up 15.8% of total gas imports, down from 19.9% in 2019-20 and 18.8% in 2018-19.

Although not helped by a short unplanned outage at Adriatic LNG in May, the drop in LNG imports reflects a large increase in Algerian pipeline imports in particular, as well as increased volumes via TAP.

But given its large pipeline import capacity, it is perhaps a surprise that Italian gas prices are generally higher than the European average. The TGP tends to set the marginal price at Italy’s PSV pricing point, which typically trades at a premium to the Dutch TTF. Even with the additional capacity offered by TAP, other pipeline routes have to be used at high capacity to avoid small but expensive import volumes via TGP setting the price.

Moreover, gas volumes entering Italy via pipeline are controlled by a few big players, of which Eni is the largest, and the TGP is not ruled by European gas market rules because the line runs through Switzerland. The expiry of Gazprom’s long-term contract for TAG pipeline volumes expires in 2023, and Switzerland is in the process of introducing EU gas regulations, but even so, large players’ dominance of the Italian gas market looks set to endure.

LNG to the rescue?

The development of additional LNG terminals could therefore play a key role in increasing competition in the Italian market, which given Italy’s heavy use of gas would benefit industrial and residential consumers alike.

Three projects, totalling 24bn m3 of capacity, have authorisations from the ministry of economic development, but none are listed as under construction, although a small-scale LNG terminal on the island of Sardinia was scheduled to start operating in the first half of this year.

If new capacity could be brought onstream in 2023-24 to coincide with the expiry of Gazprom’s TAG contract and the possible change in Swiss laws, expected around 2024, the Italian gas market could see considerable and long overdue change. Increased competition could encourage further capacity, allowing LNG to at least cap pipeline import prices and reduce or eliminate the price setting role played by the TGP.

|

Pipeline connectivity Italy has five major, geographically-diverse gas import pipelines, which together provide ample import capacity relative to consumption.

|