IEA’s Sustainable Recovery Plan Could Divide Market [NGW Magazine]

The International Energy Agency (IEA) published a ‘Sustainable Recovery’ plan June 18, in collaboration with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), putting forward policy actions and targeted investments to fix the global economy, create jobs and move the world towards a cleaner future over the next three years.

Introducing the plan, IEA head Fatih Birol said that it “offers an energy sector roadmap for governments to spur economic growth, create millions of jobs and put global emissions into structural decline.” He added that “by integrating energy policies into government responses to the economic shock caused by the Covid-19 crisis, the plan would also accelerate the deployment of modern, reliable and clean energy technologies and infrastructure.”

The IEA says that adoption of this plan 2021-23 can:

- boost global economic growth by an average of 1.1% a year;

- save or create roughly 9mn jobs/year;

- reduce global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions by a total of 4.5bn metric tons (mt) by the end of the plan;

- enable 270mn people to gain access to electricity.

But it will cost $3 trillion over the next three years through public spending and private finance, mobilised by government policies. This is only a third of the estimated $9 trillion governments are planning to spend worldwide during the next few months to rescue their economies from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The plan covers six key sectors: electricity, transport, industry, buildings, fuels and emerging low-carbon technologies. In developing the plan the IEA focused on three overarching objectives: to create jobs, to boost economic growth, and to improve resilience and sustainability.

The plan received immediate support from several governments, NGOs and investors attracted by its climate-friendly recovery, growth-orientated, proposals.

In his introduction to the plan, Birol said “as they design economic recovery plans, policy makers are having to make enormously consequential decisions in a very short space of time. These decisions will shape economic and energy infrastructure for decades to come and will almost certainly determine whether the world has a chance of meeting its long-term energy and climate goals. Our Sustainable Recovery Plan shows governments have a unique opportunity today to boost economic growth, create millions of new jobs and put global greenhouse gas emissions into structural decline.”

Birol stressed that the plan seeks to show governments what they can do – it is not intended to tell governments what they must do. But he warned that in terms of bringing emissions under control, “the next three years will determine the course of the next 30 years and beyond.”

Key recommendations

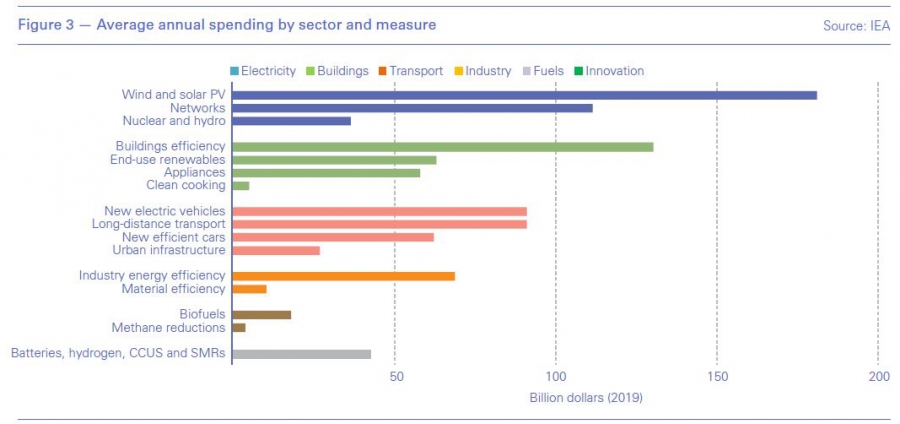

The plan makes over 30 recommendations, focusing on energy generation and consumption, that could contribute to sustainable recovery, with spending measures identified in electricity, buildings, transport, industry, fuels, innovation and energy efficiency.

It puts the emphasis on expanding existing technologies and cautions against complex, novel infrastructure projects. However, it says emerging technologies such as batteries and clean hydrogen are ready to scale up. But it is questionable whether this could be achieved in the short period to 2023.

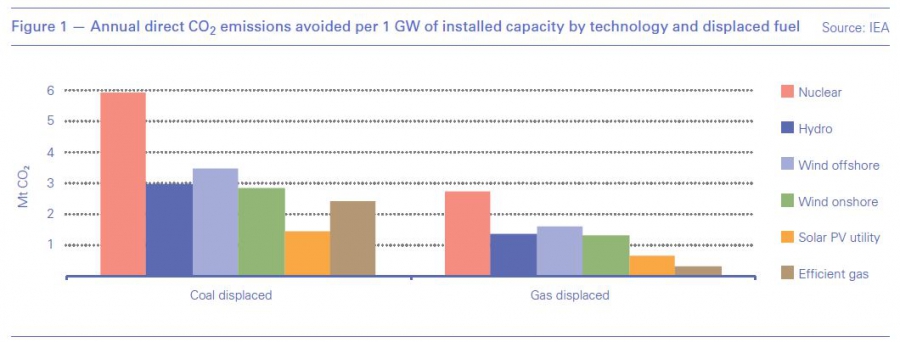

In terms of electricity, recommended measures include increased investment in wind and solar energy, biofuels and electricity grids. The plan also states that modernisation and upgrading of existing nuclear and hydropower plants in countries where licensing and approvals processes are in place could contribute to sustainable recovery. The additional advantage of nuclear and hydro is that they make a significant contribution to emissions reductions (Figure 1).

And that is exactly what the IEA recommended to the EU in its report following its 2020 review of EU energy policies. This was presented at an IEA/EC webcast on June 25 jointly with the EU commissioner for energy, Kadri Simson (see box).

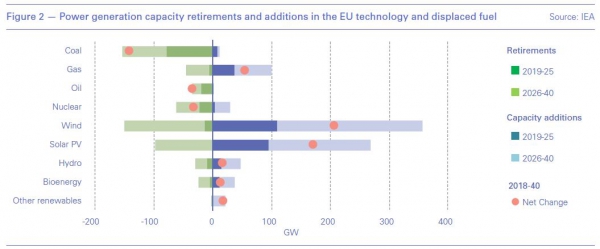

The IEA identified as a concern the security of electricity supplies in the EU as coal and nuclear plants are being retired, stating that wind and solar energy alone will not be enough. It recommended that both the retirement and the addition of more variable renewable generation plants require a stronger monitoring of system adequacy in the coming years up to 2025, but also that Europe must look beyond electricity.

Birol said “it is important to keep all technologies on the table by strengthening carbon pricing and creating a level playing-field across all fuels…and place focus on EU energy security, particularly in electricity and natural gas.” He added that “the EU and the rest of the world do not have the luxury to exclude any low or zero carbon emission technologies given the magnitude of the challenge the world is facing to lower emissions.

He warned that excluding them from the forthcoming “EU taxonomy will make it more difficult to attract investment and “more challenging for Europe to reach its climate targets, but it is up to the EU to decide.”

However, it does not appear that the EU will be taking Birol’s advice. EU member states agreed June 25 that the ‘Just Transition Fund,’ part of the EU Recovery Plan announced in May, will exclude support for nuclear energy or natural gas.

The IEA Sustainable Recovery plan also identifies measures to improve efficiency in buildings, industry and transport, including electric vehicles and new efficient cars. In fact, energy efficiency is central to the success of the plan, with about a third of the $1 trillion annual spending dedicated to energy efficiency measures.

Other identified measures include biofuels, methane reductions, hydrogen, carbon capture, use and sequestration (CCUS).

These measures could become more effective if complemented by carbon pricing or emissions standards. The IEA states that “robust carbon pricing or emission trading schemes can be effective tools to shift decisions concerning existing and new investment on to a more sustainable track.”

The IEA estimates that spending associated with this plan (Figure 3) is around $1 trillion/year ؘ– between 2021 to 2023 – amounting to about 0.7% of global GDP in each year. But it would create 9mn jobs/yr – with about 35% in the buildings sector – and put global greenhouse gas emissions into structural decline. The IEA claims that the plan would make 2019 the definitive peak year in terms of global emissions.

According to the IEA, by putting clean energy transitions at the heart of recovery, governments can help bring about the structural changes needed to ensure that economic recovery is not associated with an unsustainable rebound in CO2 emissions and local air pollution. Birol said: “This year is the last time we have, if we are not to see a carbon rebound” following Covid-19.

The IEA states that “as a result of the Sustainable Recovery Plan, annual energy-related greenhouse gas emissions would be 4.5bn metric tons (mt) lower in 2023 than they would be otherwise…. Air pollution emissions would also decrease by 5% as a result of the plan, reducing health risks around the world.”

Even though some European governments have announced stimulus plans that include green measures, such as Germany, so far when it comes to climate the record is mixed. They have spent nearly €2 trillion in state aid helping ailing companies and small business during the pandemic without any green conditions attached.

How natural gas fits into this

The IEA recommends that any wider support for the upstream sector would need to take into account the investment levels needed to meet future oil and gas demand.

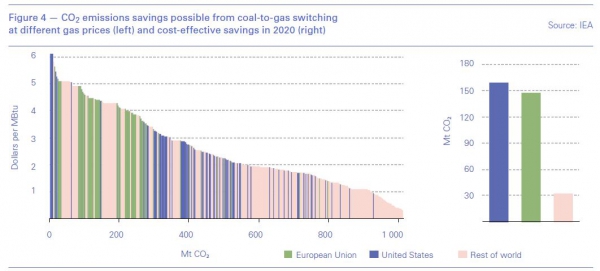

In terms of power, in 2019 coal was the largest source of electricity globally at 36%, followed by natural gas at 23%. But coal-fired power plants are the largest single source of energy-related CO2 emissions globally. The IEA estimates that cost-effective coal-to-gas switching in the power sector – especially in the US and the EU – could reduce global emissions by around 340mn mt CO2 (Figure 4).

As a transition measure, coal-to-gas switching can deliver immediate reductions of CO2 emissions and local air pollution. And with the major drop in gas prices in 2020, its economics have now improved.

An additional benefit is that gas-fired power plants are less complex to gain consent for, and quicker and cheaper to build, operate and maintain than their coal counterparts.

With the drive to shift to cleaner fuels, another option is to convert natural gas into hydrogen – the cheapest source of hydrogen – especially when combined with CCUS. The IEA suggests that a readily available way to create new demand for hydrogen is to require its blending in natural gas pipelines, which would also cut the emissions intensity of natural gas supplies.

However, IEA’s plan states that support for the upstream oil and gas sector should be linked to reducing methane emissions.

It estimates that global methane emissions from human activity amount to about 350mn mt/yr, with the natural gas industry contributing about 46mn mt/yr to this, or about 13%. Oil contributes close to 10%, or about 36mn mt/yr. It recommends that “strengthening efforts to reduce methane emissions could form an important part of any support that may be offered to the oil and gas industry,” adding that “continued and enhanced government support for reduction programmes will be important to ensure that methane emissions fall in the coming years.”

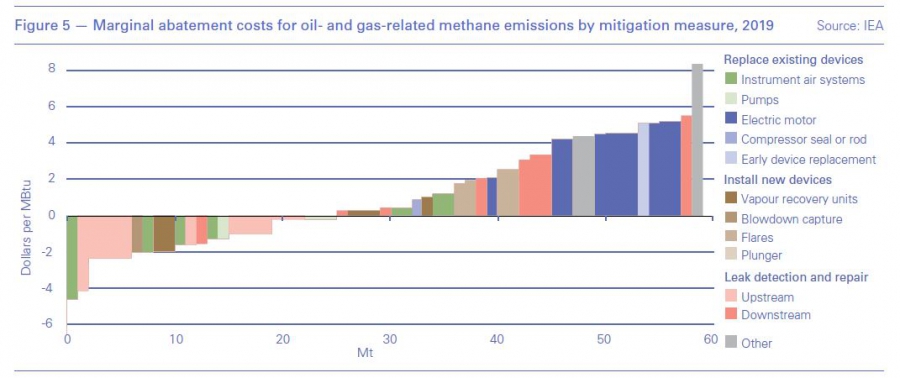

According to the IEA, It is technically possible to reduce such emissions from oil and gas operations by nearly 60mn mt/yr. Many of these emissions could be avoided at no net cost (Figure 5).

The IEA states that many of the international oil companies (IOCs) and a number of national oil companies (NOCs) have set individual or collective targets to restrict methane emissions or the emissions intensity of production. However such actions need governments to adopt suitable policies.

The IEA also recommends that the “dramatic fall in oil and gas prices presents an opportunity to cut energy subsidies without increasing end-use prices. The drop in oil and gas prices may also offer the opportunity for all countries to introduce or strengthen effective or real carbon prices.”

It recognises that “the need to tackle energy poverty and keep energy affordable, especially in periods of crisis… means that there is no single path to follow when reforming inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,” and suggests ways to deal with this.

It concludes that phasing out subsidies could deter wasteful energy consumption – also reducing emissions – and facilitate more productive spending, thus creating a more level playing field for all energy sources, boosting long-term economic growth.

Challenges

The plan follows up from the EC’s recommendations for a €1.85 trillion recovery package, centred on renewables, hydrogen, clean mobility and building renovation, with the objective of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. But this package is still being debated by member states, where for many the priority appears to be measures to save and transform national economies, not necessarily driven by climate considerations.

Similar challenges are likely to be faced worldwide, and more so in Asia and Africa where improving living standards – impacted heavily by the Covid-19 pandemic – and the energy needs of increasing populations take priority. Asia’s planners are going in a different direction.

The premier of China – the word’s largest carbon dioxide emitter – Li Keqiang said last October that coal remains China's primary energy resource. This was repeated at the National People’s Congress (NPC) in Beijing in May.

In India the prime minister, Narendra Modi, launched a virtual auction process for 41 coal blocks for commercial mining on 18 June – coincidentally the day the IEA released the Sustainable Recovery Plan. Commercial coal mining is considered central to India’s drive to stimulate growth, generate jobs, reduce import dependence and hasten the goal of a $5 trillion economy.

Coal may be struggling in Europe and in the US, but it is still king elsewhere, and likely to remain so, with Asia as its primary customer.

It is not surprising then that the support voiced so far for IEA’s plan has come mostly from western governments and investor groups.

There is also criticism from the other end of the spectrum, from those that believe the plan is not going far enough. They are criticising the IEA for saying little about the “demise in fossil fuel consumption and production needed to achieve the Paris Agreement climate goals.”

An ominous sign is that, as the IEA admits, “the Covid-19 pandemic is having a major impact on energy systems around the world, curbing investments and threatening to slow the expansion of key clean energy technologies.” It points out that only six out of 46 technologies and sectors were ‘on track’ with the IEA's Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS).

Birol said he hoped countries would seize the opportunity to fund transformation in the energy industry. But he acknowledged that the climate is not the only challenge that governments are facing…There is a risk that the global economy is melting. I share this concern, but there is also a risk that the polar ice is melting.”

And there lies the conundrum. Will governments concentrate their efforts in transforming national economies post-Covid-19 or give priority to global climate? Europe and Asia appear to be going in different directions. This would be less of a problem if they had their own atmospheres, but the risk is that the economies of those countries that shoulder the financial burden of cutting emissions also lose out to lower-priced imports.

|

EU can seize the day: IEA While great strides have been made in the European Union (EU)'s carbon emissions, greenhouse gas emissions from transport are still rising and the use of energy in buildings remains fossil-fuel intensive, said the International Energy Agency (IEA) as it launched a report on the EU June 25. The report comes out every five years, but its arrival very soon after the EU Green Deal made this edition especially timely. The IEA is working with the EC and member states to design policies to repair the economic damage of the Covid-19 crisis while making their energy systems cleaner and more resilient. EU energy commissioner Kadri Simson said that every euro spent on the recovery would be a euro well spent. Jobs, the export of technology and electrification would be beneficiaries of the move to a decentralised, digitalised and circular economy. she said, promising also an EU roadmap for a hydrogen market, which is due early July: “A clean transition is at the heart of the recovery.” She said the IEA analysis will be of great help as the EU strives to hasten the existing 2030 carbon reduction targets. A new plan for raising the ambitions comes out later this year. The IEA maintains that stronger policies are needed, particularly with regard to the carbon price and regulatory risk, and the energy sector needs to be at the heart of those efforts, as it accounts for 75% of EU greenhouse gas emissions. IEA head Fatih Birol said the European Commission's "massive [€750($830)bn] recovery plan" was "a real opportunity to boost economic activity, create jobs and support the long-term transformation of its energy sector.” Half the EU's nuclear power generation capacity is being retired over the next five years unless decisions are taken to extend the lifetimes of the plants, which provide a major part of the continent’s low-carbon electricity. This will jeopardise the EU’s chances of reaching its low-carbon emissions targets, as the existing plants are “a cheap source of zero carbon CO2. Taking them out would create difficulties,” he said. While this and the reduction of coal-fired capacity would benefit gas demand, the share of imports will grow, says the IEA, presenting risks to security of supply. Different states have different energy policies and approaches to decarbonisation, so the IEA report concludes that strong co-operation will be needed under the framework of the National Energy and Climate Plans. Hydrogen electrolysers and lithium-ion batteries could potentially be game-changers both for the EU and globally, Birol said. The IEA report also pointed to the risks of renewable energy and cyber warfare to security of supply: "In particular, EU electricity systems and markets will need to accommodate growing shares of variable renewable energy. At the same time, risks such as extreme weather and cybersecurity threats are intensifying the challenges for designing and operating electricity systems." It has been calculated that much of the EU's apparent emissions reductions over the last 30 years may in fact be tied either to the industrial collapse in eastern Europe when communist regimes toppled; or to carbon leakage, whereby the EU imports goods that were made overseas by heavy industry with which the EU could not compete. The IEA did not comment on that to NGW. |