[GGP] Why you need to look at oil & gas when you talk about Syria

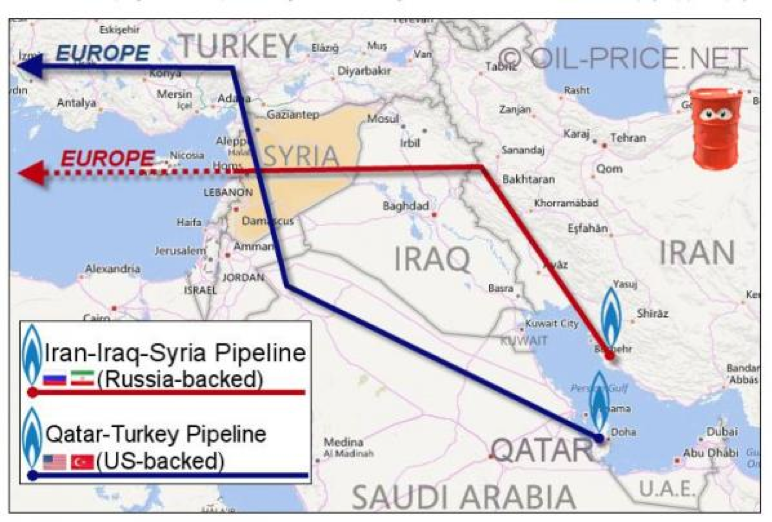

In 2016, the American magazine Politico published an article[1] by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (Bob ‘son) on the geopolitical history of the Middle East until the current Syrian war. In the piece, an important point emerged among possible causes for the Syrian conflict: a pipeline that would have started from Qatar and ended in Europe. The line, 1,500 km (900 miles) long, would have crossed Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria and Turkey.

We are talking about the largest gas field ever, divided between Iran and Qatar known as South Pars (Iran side) / North Dome (Qatar side).

Apparently in 2009 Assad rejected this pipeline and proposed another one – blessed by Russia – which would have started from the Iranian side of the said gas field, crossing Syria to reach the ports of Lebanon.

The second pipeline would have made Shiite Iran, not Sunni Qatar, the main supplier to the European market.

Pipelines to Europe from Oilprice.net

The History returns

The Middle East has been critical for a century, when Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, converted the British navy from oil from coal and World War 1 brought to light the issue of crude oil supplies[2]. TheSykes-Picotagreement (1916) and the Red Line agreement (1928) divided the area into British and French spheres of influence. Syria and Lebanon fell into the latter.

It is at this historic moment that the Balfour Declaration (1917) for the development of the state of Israel came in and, three years later, the Treaty of Sevres, between the allied forces and the then Ottoman empire. The latter (Section 3, paras 62-64) mentions the Kurdish people and their possible governmental autonomy for the first time.

Having done this necessary, history quick introduction, let’s move on the analysis considering the current forces on the ground.

Pipeline from Iraq to Turkey from The Economist

What would the Turkey want?

The last Turkish military action in the Rojava (northern region of Syria, also Syrian Kurdistan), can have different interpretations. At first glance, it could be a message addressed to the internal Kurdish forces (PKK). Another possible interpretation could be a bold delimitation of the area crossed by the very important oil pipeline carrying Iraqi oil (Kurdish) to the Ceyhan terminal in Turkey (see fig.2).

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, seems to balance Russian and US interests. One on hand he has signed agreements for the first nuclear power plant. Using Russian technology worth $20bn it will be built in Akkuyu in the east of Turkey.

He let himself be photographed with the Russian president Vladimir Putin and the Iranian president Hassan Rouhany. On the other hand, he took a “pro-western” position when US, France and the UK fired their missiles at Syrian positions after the humanitarian disaster of Dhouma.

Let’s forget the military aspect for a while and the various mutual accusations between the pro and anti Assad camps and instead take a look at the energy element. In a certain way, the agreement of the first nuclear power plant in Akkuyu may have been a trade-off between Turkey and Russia for the (temporary or permanent) abandonment of the pipeline that would have brought Iraq's Kurdish gas to Ceyhan, recalling that Russia’s biggest oil company Rosneft, before the Iraq/Kurdistan referendum in October, offered to finance the project.

A study[3] by the English think thank OIES in 2016, showed the possibility of about 10bn m³/yr being exported from Iraqi Kurdistan to Turkey. This is almost equal to the amount of gas flowing from Azerbaijan through the Southern Corridor (under construction).

If the Kurdistan-Iraq gas pipeline to Turkey was “parked or scrapped”, the Akkuyu nuclear power plant could fit perfectly as compensation. Some might argue that maybe the nuclear plant could also be a kind of compensation for a possible abandonment regarding the S-400 systems that Russians have proposed, much to the alarm of US and its Nato allies. Turkey is (still so far) a Nato member. However only time will perhaps make these aspects clearer.

What would Russia want?

As we said above, for the Kremlin the Qatari pipeline was not the best option, threatening Russia’s share of Europe’s gas market. For an instant, let’s forget this hypothesis and instead concentrate on another aspect. Probably to Russia, keeping the Syrian state alive has been an existential imperative from an anti-globalist perspective: strengthening the pro-nationalistic brand (globally).

In a certain sense Putin has entered history to help close (or postpone) the chapter of the Orange Revolutions and Arab Springs and to raise the curtain on Autumn for liberal democracy.

We have to remind that Russia is undergoing a delicate existential moment: if Ukraine joins Nato enemy troops could be a few hundred kilometers from its borders. And it is well known that what always has protected Russia over the centuries from invasions has been its "depth", that means long distances.

Nevertheless by intervening in Syria Russia has entered the eastern Mediterranean: supporting the Assad government guarantees the Tartus (and sovereignty over it) for 49 years since 2017 and therefore a de facto Russian naval and military presence in the eastern Mediterranean.

We have to remind also that Russia is Europe's leading gas supplier and that new Mediterranean gas discoveries in the long term could balance the steady decline of the North Sea reservoirs[4]. The future potential gas discoveries in Lebanon should also be included in this perspective, and we will talk about it in the future.

The marketing of S-400 weaponry systems and nuclear technologies (the Rosatom power plants) would generate incoming cash flows and establish long-term international relations. George Friedman, the founder of the American think tank Stratfor, in his book[5], estimates that the population of Russia could fall by about 25mn by 2050. This demographical phenomenon, although attenuated after the collapse of the Soviet Union, has had as an economic effect on the labour-intensive oil and gas industry.

A smaller workforce engaged in the productive sectors creates labour availability in the armed forces to protect the borders, which in this period are particularly guarded. Hence, we could argue that the sale of protection systems and associated technologies becomes a strategical economical matter.

What would the US want?

For a moment let’s forget peoples’ right to self-determination and democracy, of which the US has been the bulwark: it is difficult to describe the US position in few lines. For sure one target is the reduction of Iran’s influence in the region and boosting that of France and Saudi Arabia, “allowing” Russian growth in the Middle East region. This could be a trade-off for the stability of the oil price (read Russia and Opec agreement, which is important for US shale oil industry. And also more leverage over North Korea and the South China Sea. Yes, because if, for the US the control and influence of the Middle East is strategic, the reduction of its power in the Pacific is an existential threat. We are talking about the control of the seas and trade.

What would Israel want?

More security. This means according to Israel’s perspective, less Iranian influence: interrupting the territorial continuity from Iran to Syria and Lebanon to the Golan and creating a buffer zone protected by Hezbollah. But also, having a pseudo ally in the shape of Kurdistan, and no longer being the only “new state” in the Middle East.

The Financial Times[6] reported that around 2/3 of Iraqi Kurdish oil passed through Israel with final markets in Italy, France and Greece. The trade would have been mainly through prepaid agreements facilitated by oil trading companies.

Oil produced from northern Iraq reached the terminal of Ceyhan in Turkey and from there it moved in the Mediterranean, reaching the final markets.

What would Iran want?

Kamenei’s Iran has a clear position, on the Iraqi Kurdish referendum he said: the vote “represents a betrayal of the entire region and a threat to its own future”. At the time, he accused the US of trying to create “another Israel” in the Middle East. Rouhani’s Iran would rather avoid being hit again by sanctions. We have to consider that before the sanctions, Iran produced about 1mn barrels/day less than at present.

Iran would like to guarantee investors a stable and secure environment but the ending of the nuclear deal is just around the corner.

What does France want?

Macron's France would like to revive its role in the region, remembering that beyond Syria lies Lebanon and here the gas resources are to be developed. Then we have the case fof Cyprus where a few weeks ago the response of the Turkish leader Erdogan, was not so generous. The gas supply in the eastern Mediterranean is a game too important to stay out of. He would like to protect his energy industry: in Iran, Total is (was?) in pole position to develop the giant South Pars gas field – sanctions permitting. We'll see if Macron has managed to convince president Donald Trump to leave things as they are but to date that would seem unlikely.

What does Saudi Arabia want?

The Saudis essentially want to contain Iran. In October King Bin Salman visited Moscow for the first time ever and the result was an important agreement that granted stability and boosted the oil price. The Saudis are now undergoing profound transformation and renewal. If King Salman was in Moscow to meet Putin, the crown prince Mohamed Bin Salman, the future of the kingdom seems to look more to the West. A stable price is necessary to implement the necessary reforms and above all to diversify an economy that is practically dependent on oil; and for the initial public offering of Saudi Aramco – the jewel in the crown.

We need a suitable barrel price: the International Monetary Fund estimated in 2016 that for the first five producers in the Middle East this means, at least $60/barrel to meet national budgets (safety, health, education...).

The latest comments of Bin Salman regarding the legitimacy of the people of Israel to have their State are important signs. The Saudis and Israel have in common both a serious threat (Iran) and a great ally (USA).

What does Kurdistan want?

Despite the Treaty of Sevres, other treaties such as the Treaty of Lausanne have not raised the matter of a Kurdish state. We must wait another century before talking about that again. But in practical terms, the Kurds are fighting in Syria and Iraq against the Islamic state and this could be the time for them to win their place in history. On October 4, 2018 the Iraqi Kurds had a referendum: the issue was the city of Kirkuk, freed from Islamic State thanks to the Kurdish Peshmerga. The city, a primary centre for Iraqi oil production (15% of reserves and 40% of Iraqi production under Saddam), was lost by the central government in 2014.

Will see.

(This is the English version of the previous release[7] on Start Magazine)

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.

[1] https://www.politico.eu/article/why-the-arabs-dont-want-us-in-syria-mideast-conflict-oil-intervention/

[2] https://www.geopolitica.info/middle-east-energy-future/

[3] https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/under-the-mountains-kurdish-oil-and-regional-politics/

[4] https://www.naturalgasworld.com/european-gas-from-one-sea-to-another-31622

[5] The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century

[6] https://www.ft.com/content/150f00cc-472c-11e5-af2f-4d6e0e5eda22

[7] http://www.startmag.it/energia/siria-pesano-gas-petrolio/