[GGP] Proposed Gas Directive amendment and the EC-Gazprom settlement

During the spring of 2018, after seven years of deliberations, the European Commission concluded its investigation of Gazprom regarding alleged abuse of its market position in Central and Eastern European gas markets. The outcome is a finely crafted settlement setting out rules and guidelines for acceptable future market behavior. As the settlement is based on mutual agreement, while at the same time accepted by the European Commission as adequate to bring a locally dominant competitor to heel, it has a good chance of succeeding. This settlement completely changes the context within which the proposed Gas Directive amendment was formulated. From this point of view, it seems surprising that the proposed amendment, which adds very little to the enhancement of competition in these markets, is still being discussed without reference to these changed circumstances. Not only could it potentially put at risk what has been achieved in the settlement but, it might also endanger future investments in incremental gas infrastructure in a number of areas of the European Union.

This report is a supplement to a previous report, “Analysis of the proposed gas directive amendment”, that was published in March 2018. The work has been commissioned by Nord Stream 2.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

1. Background

In September 2012, the European Commission opened formal proceedings against Gazprom for possible abuse of a dominant position in several gas supply markets in Central and Eastern Europe. In 2015, the allegations were more precisely formulated in a Statement of Objections, claiming that Gazprom was pursuing a strategy to divide gas markets, in breach of EU anti-trust rules, that prevented competition in the markets of Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia. The claim was based on three issues: (1) territorial restrictions on the resale of gas (2) unfair pricing policies, and (3) use of a dominant position to obtain unrelated commitments concerning transport infrastructure.

FIGURE 1: THE EIGHT AFFECTED MEMBER STATES AND THEIR PIPELINE CONNECTIONS WITH RUSSIA

These obligations address the Commission’s competition concerns and achieve its objectives of enabling the free flow of gas in Central and Eastern Europe at competitive prices.

European Commission – Press Release 24 May 2018 – Antitrust: Commission imposes binding obligations on Gazprom to enable free flow of gas at competitive prices in Central and Eastern European gas markets

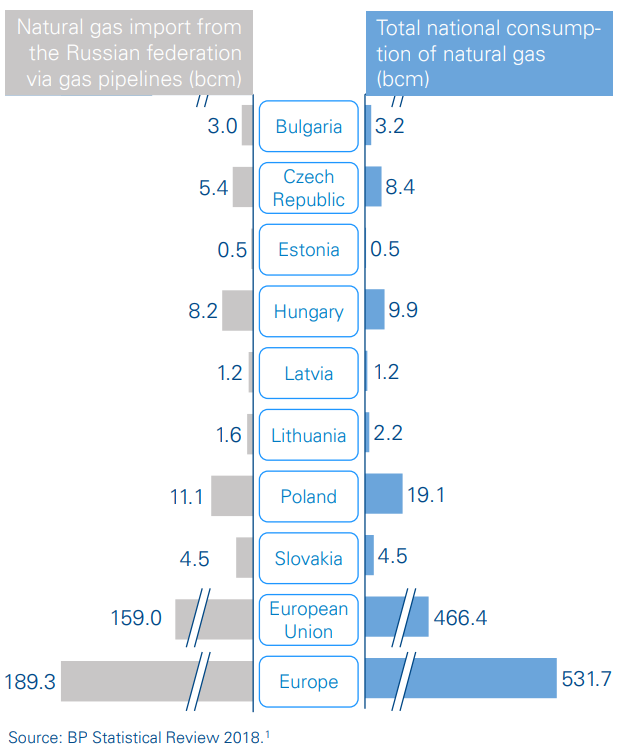

As can be seen from Figure 2, both consumption and imports from Russia in the affected member states are relatively small in comparison to the EU as a whole, and their import dependency on Russian gas is much higher.

It is noticeable that both Poland and the Czech Republic imported significant volumes from sources other than Russia in 2017.

FIGURE 2: CONSUMPTION AND IMPORTS FROM RUSSIA IN THE EIGHT AFFECTED MEMBER STATES IN 2017

Gazprom responded in 2016 with a proposal for commitments to alter its market behavior. It offered to remove all contractual barriers to the free flow of gas in Central and Eastern Europe. It also agreed to remove contractual barriers in export contracts to Bulgaria and Greece that prevented transmission system operators (TSOs) from making interconnection agreements with neighboring states. In addition, it offered existing buyers the right to change the delivery point of gas. And, last but not least, Gazprom offered to introduce competitive pricing benchmarks, including western hub prices, into its price review clauses, and to increase the frequency with which such reviews might occur . The recent settlement between the European Commission and Gazprom builds on these commitments, which are, each on its own and in combination, important concessions and a significant step forward in terms of improving competition in Central and Eastern Europe, since they, as we shall see below,

(1) enable the free flow of gas across borders to any buyer willing to pay competitive prices for commodity and transport,

(2) provide buyers with influence over preferred delivery point, and

(3) ensure that gas prices in Central and Eastern European markets reflect prices at competitive Western European hubs.