Gazprom, Ukraine, EC and the 11th-hour deal [NGW Magazine]

After an autumn of impasse, the Normandy Format talks, held between France, Germany, Russia and Ukraine in Paris on December 9 provided a new impetus to negotiations. A few days after the CEO of Naftogaz boosted gas prices at European hubs with his observation that the chances of a deal were negligible and shrinking daily, on December 20, Russia and Ukraine signed in Minsk a protocol on gas co-operation.

Gazprom undertook to continue to flow natural gas through Ukraine after the current transit contract expires on January 1, 2020, with the minimum volumes for the next five years (2020-2024 inclusive).

On December 30 Gazprom, Gas Transmission System Operator of Ukraine (GTSOU) and Naftogaz reached a final and legally-binding compromise. The “package deal” included a five-year transit ship-or-pay transit agreement between Gazprom and Naftogaz; an interconnection agreement between Gazprom and GTSOU; and an agreement between Gazprom and Naftogaz to abandon mutual legal claims.

Parameters of the transit agreement

Naftogaz agreed to serve as an organiser of the gas transit over the five years and, according to Gazprom’s statement, will assume any and all risks that arise in the transition period. Naftogaz will book in all 225bn m³ of capacity on behalf of the Russian gas company, comprising 65bn m³ for 2020 and subsequently 40bn m³/year. GTSOU will charge Gazprom a transit tariff that is fixed for five years plus a commission.

Neither Gazprom nor Naftogaz disclosed the value of that commission or of the transit fees. However, both Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenski and Naftogaz executive director Yuriy Vitrenko announced that Ukraine would receive at least $7.2bn over the five years. This is a big drop from the $2-3bn/yr it has been used to.

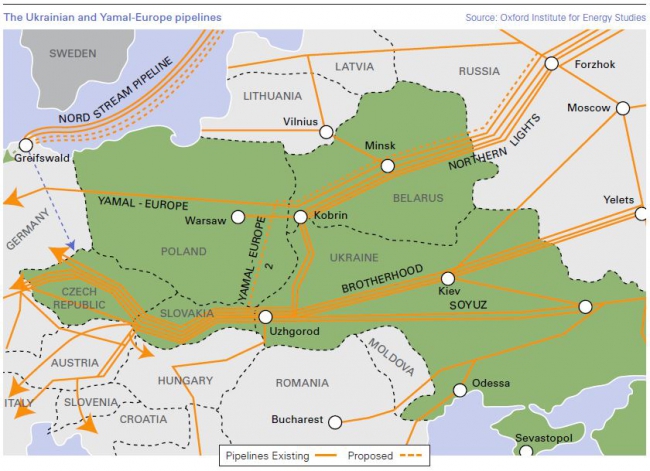

This gives a rough figure of around $32/’000 m³/yr including VAT of 20% and correlates with the transit tariffs published by the GTSOU December 24. For example, the GTSOU transit fees for the delivery of gas from Sudzha near the Russia-Ukraine border to Slovakia (exiting at Uzhgorod) is expected to be $30.83/’000 m³; to Hungary (exiting at Beregovoe) it is $30.31/’000 m³; and to Moldova (exiting at Ananiev. Limanskoe or Grebeniki) it is $29.02/’000 m³.

However, Ukraine’s regulatory environment is still far from being fully in line with EU standards. Furthermore, the reform process was unnecessarily delayed by internal political and power struggles in Ukraine. For example, the cabinet of ministers and Naftogaz have disagreed on the unbundling process from the very beginning.

The government clearly preferred the “ownership unbundling model” whereas Naftogaz wanted to proceed with the “independent system operator” (ISO) model, which is how it turned out.

Market observers recognise progress on Naftogaz unbundling but say that a lot more needs to be done despite GTSOU unbundling being nominally complete by the deadline of January 1 when Ukrtransgaz and “Magistralnye gazoprovodi Ukrainy” (MGU) signed all the documents necessary to allow the transfer of GTSOU assets to MGU.

The new TSO might be still affected by the issue of Ukrainian distribution network operators’ (DNO) debt which in November 2019, Ukrtransgaz estimated would be about hryvnia 20bn by year-end. Naftogaz says the debts remain on the books of Ukrtransgaz. However, the GTSOU is responsible for the international gas transit and also deliveries to domestic customers. Therefore, an issue of potential future DSO debt might affect GTSOU as well.

In December 2019, Ukraine’s energy regulator announced the DNO tariffs would go up by 30% in 2020. This increase, however, might not be sufficient to fully resolve the debt issue and allow profitable functioning of the DSOs, even if it does reduce the debt growth rate.

These inefficiencies were confirmed by the Ukrainian side. Speaking to media, Naftogaz’ CEO Andriy Kobolyev said that Gazprom’s request was not an unexpected demand. From the point of view of the legislation governing Ukraine’s gas market, he said the country has not yet reached compliance with EU energy legislation,” he said.

Settlement of the legal issues

On December 27, ahead of the signature of the final deal, Naftogaz received from Gazprom $2.918bn, comprisingthe compensation awarded by the Stockholm Arbitral Tribunal in February 2018 and accrued interest. The Ukrainian gas company also agreed to withdraw pending arbitration and legal claims, including a new $12bn claim with the Stockholm arbitration tribunal and also agreed not to file any new (arbitration) claims. Gazprom was also waived a fine imposed by Ukraine’s antimonopoly committee of Ukraine (around hryvnia 172bn ($7.2bn)).

According to Naftogaz, the issue of gas supply was not subject to the package agreement but Gazprom earlier confirmed the possibility of direct gas sales to Ukraine, the price to be linked to NetConnect Germany’s benchmark hub.

Market realities

Previous European Commission and Naftogaz transit proposals were not compatible with the market and infrastructure realities on the ground. In April 2019, Yuriy Vitrenko proposed booking 60bn m³/year of transit capacity for ten years. However, even this reduction of transit demands were not realistic. But the new agreement is compatible with the market realities. For example, IHS Markit estimates that transit through Ukraine (with Nord Stream-2 and Turk Stream being fully operational) may be 28bn m³/year and more by 2030, depending on Gazprom’s needs.

Infrastructure constraints

The current state of Ukraine’s infrastructure is hardly compatible with initial plans to offer long-term (and large scale) transit services. More than 60% of the pipelines are over 33 years old and only three of the country’s compressor stations are less than ten years old. According to its Ten-Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP) 2019-2028, Ukrtransgaz, Naftogaz transportation branch, is planning to invest hryvnia 56.87bn, which includes around $1.25bn for the pipelines and compressor stations. Most of these funds have been committed to the construction of an interconnector with Poland and the refurbishment of the Ukrainian section of the Urengoy- Pomary-Uzhgorod pipeline, starting from Sudzha in the east. Its nameplate capacity is 32bn m³/yr.

In October 2018, Naftogaz announced plans to invest only hryvnia 7.3bn ($308mn) in gas transportation assets last year, while in an interview with Ukraine’s daily Ekonomicheskaya Pravda published August 15, Yuriy Vitrenko confirmed that the expected life span of Ukraine’s gas transportation system was 15 years. In this situation, the offer is more realistic than the initial plan of 60bn m³/yr ship-or-pay + 30bn m³/yr of flexible capacity.

Economic situation

As surprising as it may seem, Ukraine’s fragile economic growth – estimated at 3% in 2019 by the IMF – may be threatened by a stronger hryvnia: it rose 19% against the dollar in 2019. The inflow of speculative foreign capital into state-owned and private debt increases the volatility of the country’s financial sector and may lead – in case of adverse events – to a rapid devaluation of the national currency.

This upwards trend has already had an adverse effect on the budget and increased Ukraine’s current account and trade deficits. The country’s revenues are heavily dependent on the export of agricultural products, raw materials, steel and also on the remittances of Ukrainians living and working abroad. In January – November 2019, Ukraine’s national budget missed its target by hryvnia 56bn, or 6%. Furthermore, the trade deficit in January – October 2019 increased 3.3% year on year to $10bn, while in November 2019 industrial output went down 7.5% year on year.

Last but not least: the issue of external debt repayment also played a certain role in pushing the Ukrainian government and Naftogaz towards a compromise on the gas transit. Ukraine’senterprises, the Central Bank, financial institutions and the government have to repay $17.06bn (around 40 % of Ukraine’s budget), comprising $13.06bn debt and around $4bn in interest. The first quarter of this year is a peak reimbursement period (ca $5.42bn).

So not only would the absence of transit have created problems with supplying customers inside Ukraine, it would have also have drastically increased the country’s current account deficit and led to a potential bankruptcy of the GTSOU.

For Gazprom, the settlement of legal disputes has unfrozen the company’s assets in Europe. On November 13, Russian daily Vedomosti reportedthat Gazprom decided to suspend the issue of its Eurobonds nominated in Swiss francs owing to the risk of the assets freeze. A transit compromise therefore facilitates Gazprom’s usual conduct of business abroad.

Agreeing a deal has also allowed Gazprom to access additional capacity which may be needed to meet gas demand in Europe in the near future.According to Wood Mackenzie, Europe will need to import 77bn m³/yr more by 2025 as a result of EU decarbonisation policies and the fall in domestic gas production in Europe. While liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports to the EU are on the rise, these will alone not be sufficient. Additional pipeline imports from both the Caspian and Russia will thus be handy, increasing the need for Ukraine’s gas transportation system.

The compromise also allows a safe and stable supply of gas to Moldova, a country with no gas storage and a market which cannot be ignored in an increasingly competitive environment. According to a communique from the government, Gazprom’s gas deliveries to the country are expected to reach at least 4.38bn m³ in 2020.

The Gazprom-Naftogaz deal and adoption of the EU energy rules also opens up the prospect of direct sales of Gazprom’s gas to Ukrainian customers that bypass Naftogaz – an opportunity not to be missed.

The ability to access 65bn m³ of transit capacity will resolve all of Gazprom’s probable and improbable 2020 supply bottlenecks and complete its infrastructure projects in Europe. Therefore, the compromise reflects the objective facts, rather than being merely the consequence of an arbitrary political decision: it considers the state of Ukraine’s gas transportation system, the availability of alternative infrastructure, gas demand in Europe and delivery logistics.