Gas is there for the long run in China's energy transition [Gas in Transition]

Natural gas has a long-term role to play in China’s energy transition. The country’s economic growth model is resource- and energy-intensive – something that has created concerns not only for environmental but also for economic sustainability. Yao Li expanded on this and its importance to China’s energy transition.

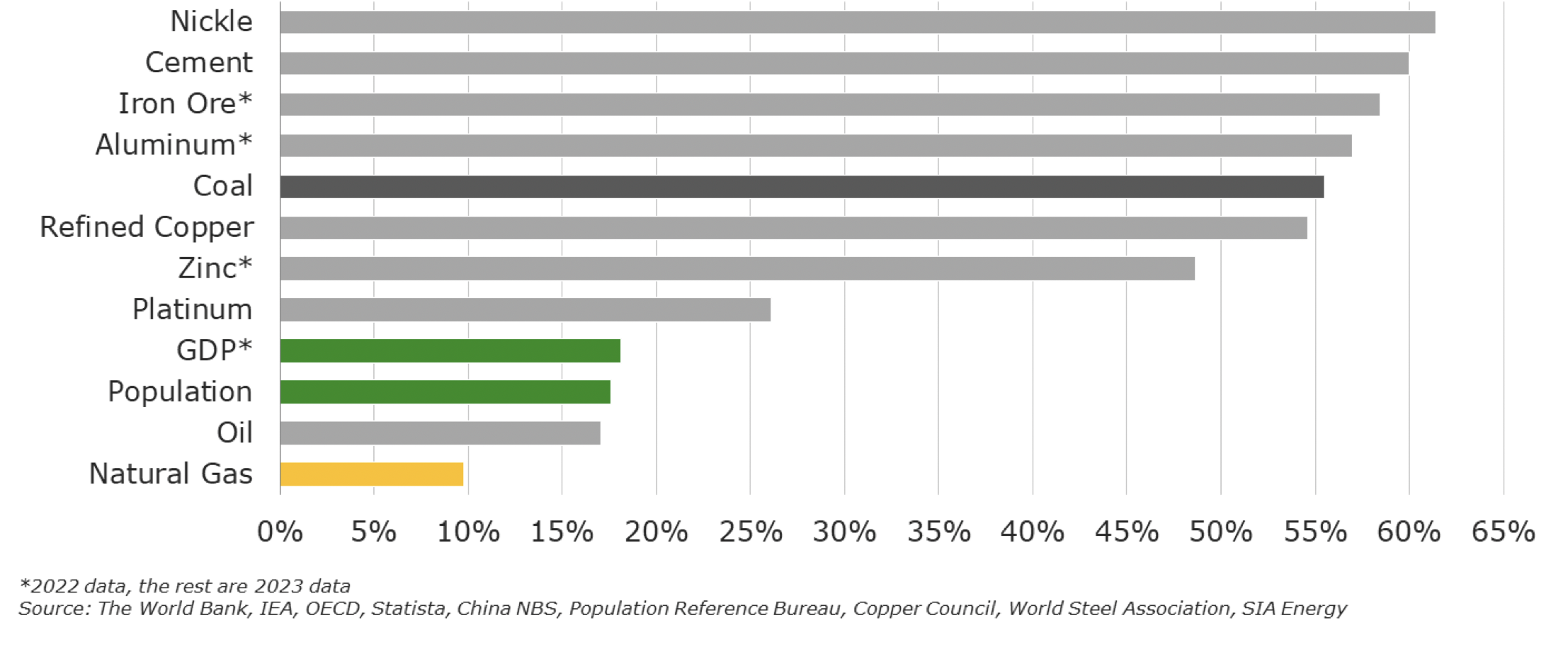

China produced 18% of global GDP but used more than half of global coal, ferrous and non-ferrous commodities in 2023 (see figure 1). This resource- and energy- intensive “world factory” model is unsustainable for two reasons:

-

China made too little value-added in proportion to its natural resource consumption and environmental damage (GHG emissions included) in the world. It is important its economy moves away from the “sweat shop” and “simple processing” model and transitions to higher-end, higher value-added and greener production of goods and services.

-

China’s coal consumption is disproportionately high in comparison to the world, especially in terms of dispersed low-grade coal burning in non-power sectors with little emission treatment (roughly 47% of coal use and 27% of total primary energy mix). This is the primary reason for the country’s air pollution problem and it has to be addressed.

With zero particulate matter emissions, natural gas is part of the solution to China’s air pollution problem.

Figure 1: China’s share in global commodity consumption

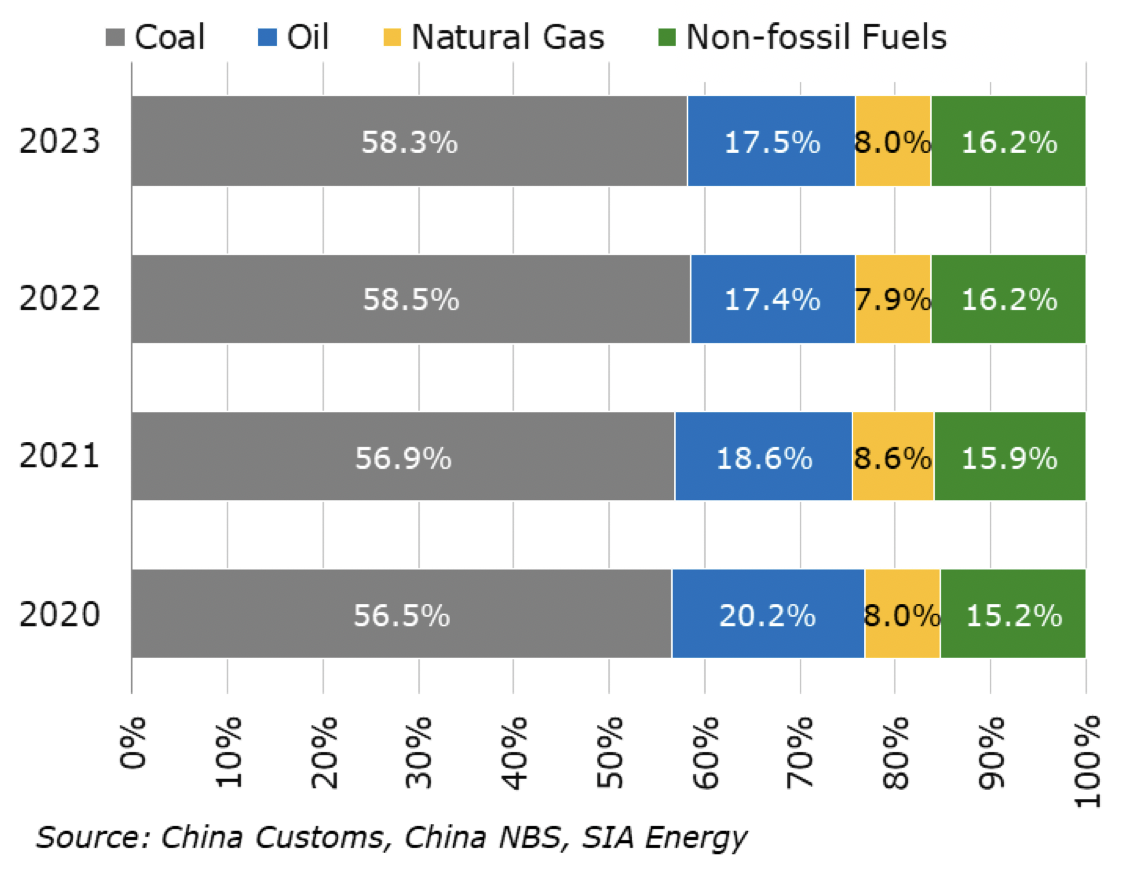

Coal still provides more than 58% of China’s primary energy supply mix, up from 56.5% in 2020 (see figure 2). Coal-to-gas switching will happen firstly and predominantly in the industrial sector, but also in the power sector (especially in the affluent coastal markets).

Figure 2: China’s primary energy supply mix

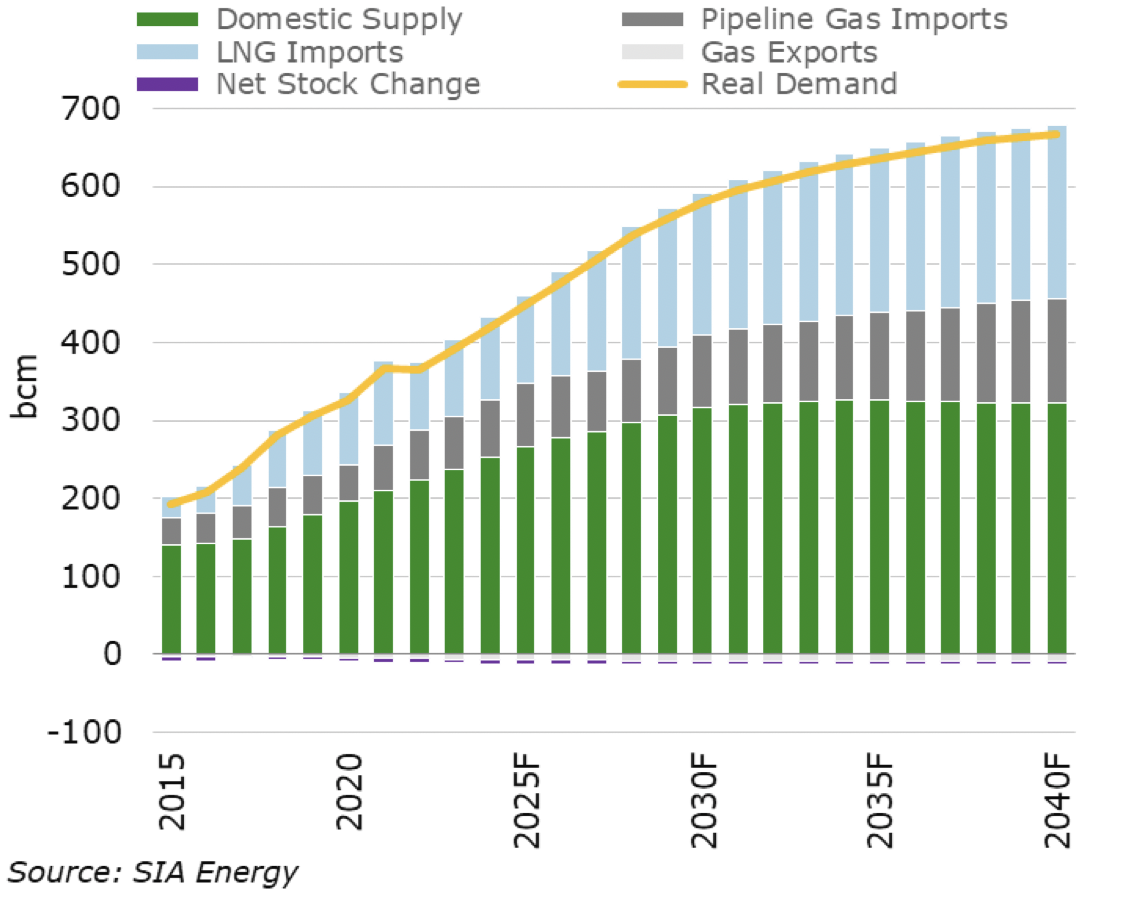

That means that natural gas demand will grow, with supply supported by strong domestic gas production.

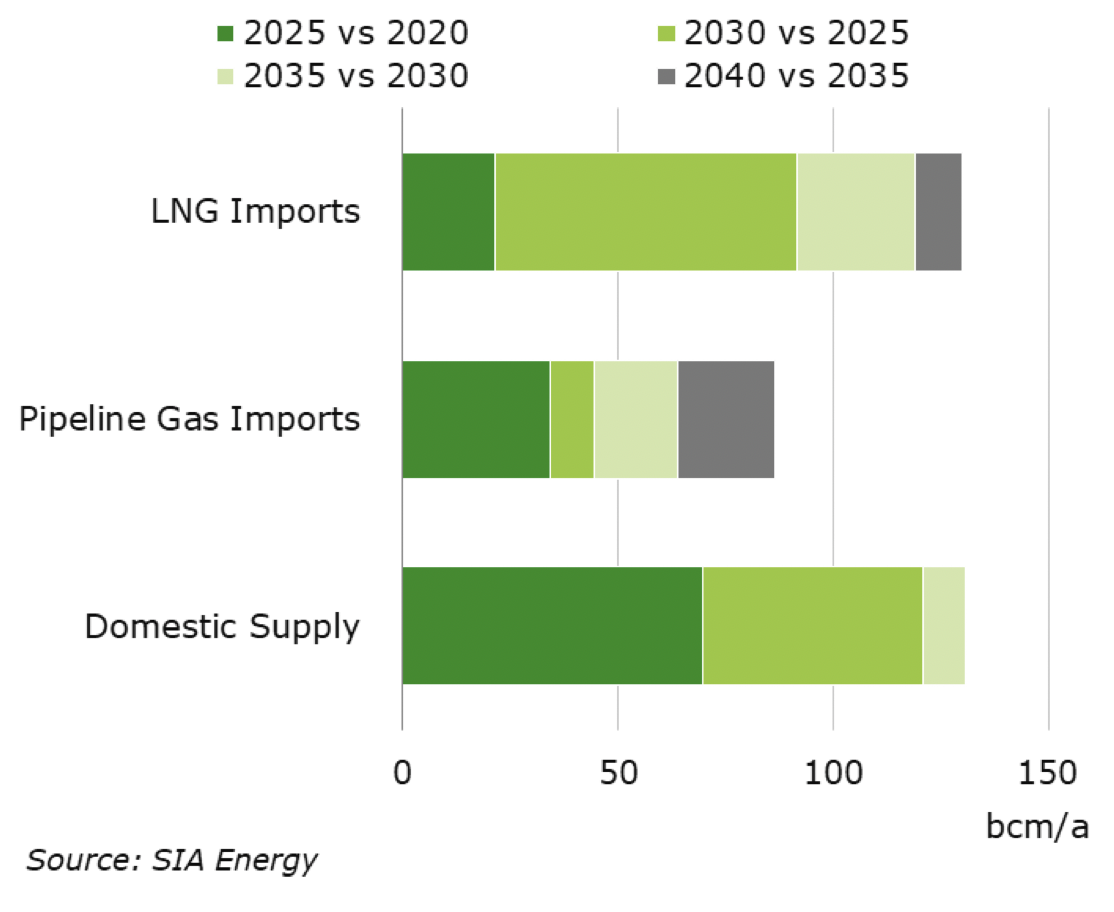

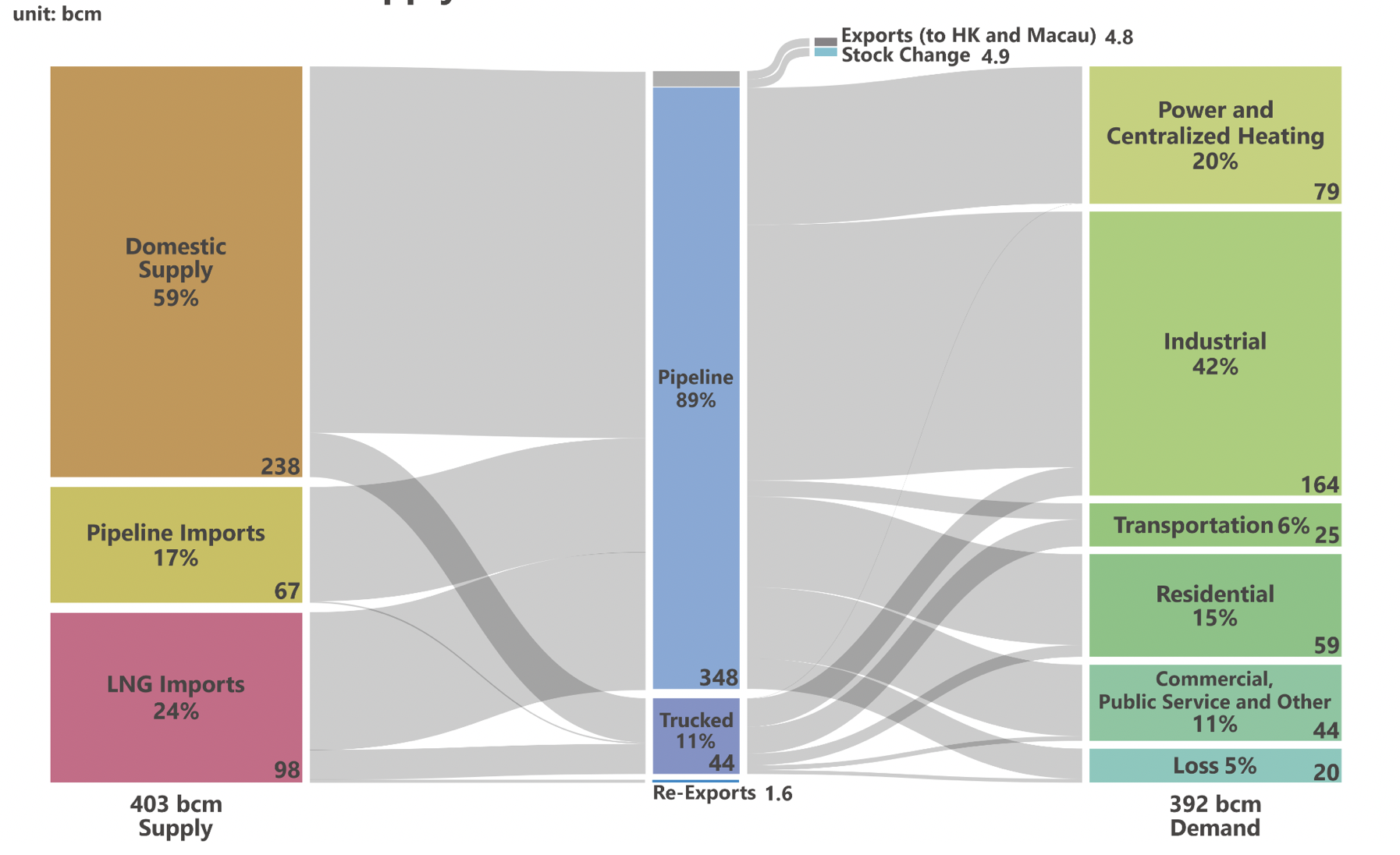

Real gas demand is expected to grow from 392 bn m3 in 2023 to 667bn m3 in 2040 (see figure 3). Even though domestic production will make up the largest incremental gas supply during the 2024 to 2040 period, it will not keep up with the pace of demand growth. As a result, gas import dependency will go up from ~40% today to ~50% by 2040. Imported LNG will contribute an equivalent share to the incremental supply during the next 16 years as domestic output, but LNG growth will be concentrated (+70bn m3) in the 2026 to 2030 period (see figure 4).

Figure 3: China’s gas supply forecast to 2040

Figure 4: Incremental gas supply by source and by phase

Nevertheless, at present gas penetration in China’s primary energy is relatively low, at 8% in 2023 (the same level as in 2020), but it is expected to grow by 2050.

China has been a supply- and infrastructure- constrained market during the last 30 years. But this constraint will be fundamentally lifted in the future. Gas penetration will go up, driven by sufficient contracted supply and abundant import infrastructure capacity, increased market liquidity, and more affordable prices during the 2026 to 2030 period as global LNG supply ramps-up. However, given the sheer size of the Chinese economy and energy use, gas penetration will never be as high as in the OECD economies. Based on China’s energy consumption today, it would take 40 bn m3 of natural gas equivalent of low carbon fuels to displace 1% of coal penetration in the primary energy mix.

Imported LNG will make a bigger share in incremental supply in the next 16 years in comparison to imported pipeline gas. Russian pipeline gas will be competing head-to-head with Central Asian pipeline gas, but not with LNG. This is because:

-

Geographic coverage is different: imported LNG will mainly be imported to coastal south and southeast, while Russian gas will only reach northeastern and northern China, while Central Asian gas will be re-oriented and squeezed to inland China.

-

Pipeline gas may be cheap at the Chinese border, but will not be so price competitive in the coastal market centers after thousands of kilometers of transmission cost, especially when LNG prices based on long-term contracts (linked to the oil price) and spot LNG prices (linked to JKM) are low.

A question that arises is what is the likelihood of increased Russian pipeline gas supplies, especially after the recent visit of President Putin to China, and by how much and when?

The Power of Siberia 1 gas pipeline (PoS-1) will continue ramping up to 30 bn m3 this year and to 38 bn m3 by 2025. The Russian Far East Route will start operating in 2026 and will ramp up to 10 bn m3/yr by 2029, if the original schedule is kept. But when it comes to PoS-2, time is on China’s side. The Chinese market is well supplied up to 2030. When and if any new deal is reached, it will be on Chinese terms. SIA forecasts that the PoS-2 pipeline will come online around 2035.

LNG demand growth is expected to remain strong, but where will it be sourced from? And what is China’s role in global LNG markets expected to be?

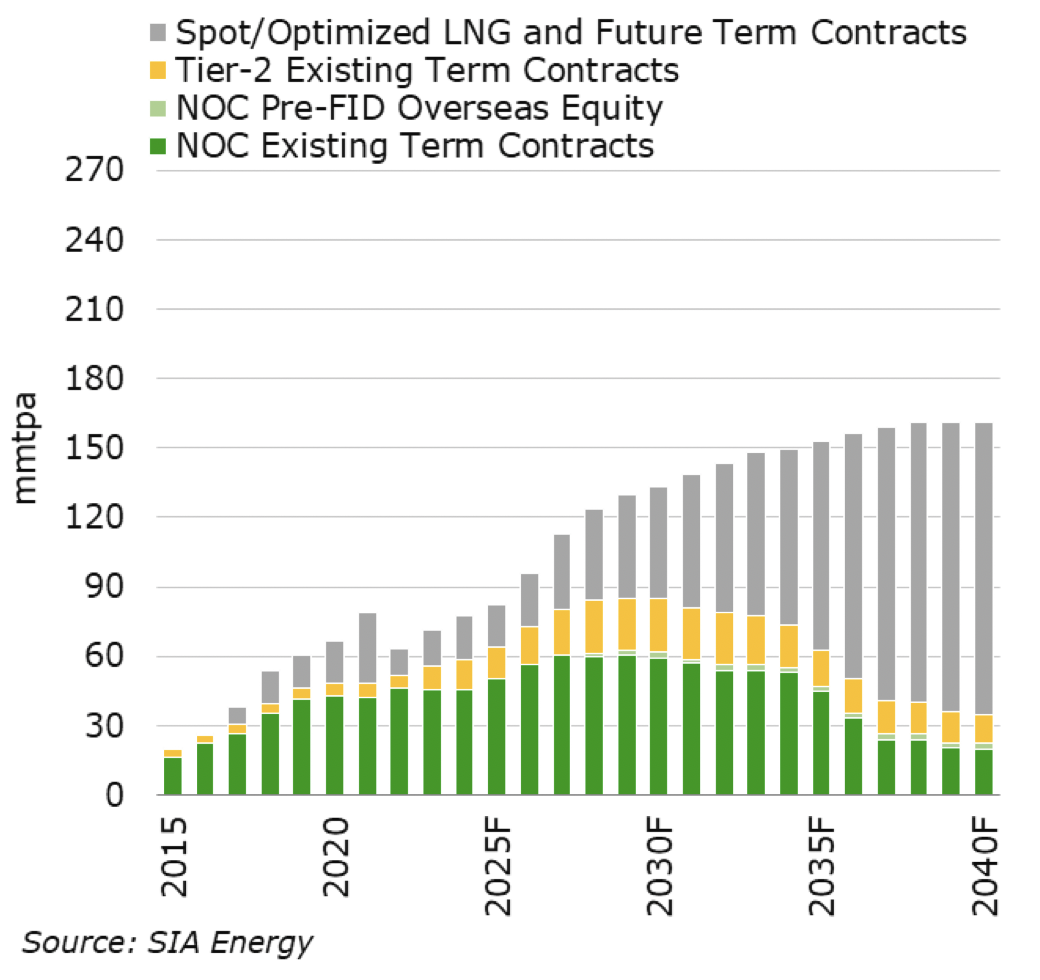

LNG imports are forecast to grow from 71mn tonnes/year in 2023 to 85mn t/yr in 2025, to 136mn t/yr in 2030 and to 160mn t/yr in 2040 (see figure 5). It will be sourced from diversified sources. China’s role in global LNG markets will grow not only because of its expanding import scale but also its ability to become a balancing market like Europe. But that will require China to accelerate its marketisation and price deregulation process.

Figure 5: China’s LNG import forecast to 2040

In the meanwhile, climate commitments and decarbonisation are increasingly influencing China’s energy mix and the role of natural gas.

The Chinese government is committed to achieving a carbon emission peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. In the industrial sector, where fuel is needed to be burnt in the boilers and furnaces and renewable’s role is limited, natural gas will be the most important clean fuel to displace coal (see figure 6). The industrial sector is responsible for 61% of China's CO2 emissions.

Figure 6: China’s natural gas supply and demand flows 2023

In the power sector, China has already increased renewable power to 50% of installed capacity (for example, solar power capacity alone increased to 217 GW in 2023), but the power system will need more flexibility to accommodate capacity spikes and the increasing volatility/intermittency of renewable power generation. Gas-fired power will play a growing role in peak shaving. A spot electricity market is evolving to accommodate this and it is called upon to price the value of peak shaving fairly.

On a more controversial issue, Yao Li said at FLAME that she welcomes the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – the world’s first carbon border tax. This was a statement that caused a stir.

She said she appreciates what the EU is trying to accomplish with CBAM and the potential it holds for speeding up global decarbonisation through increased competition. CBAM aims to create a level playing field for internal EU products and imported goods and, even though not many details are available yet, the scheme intends to ensure fair treatment. This, for example, is apparent in the gradual phasing-in of CBAM, mirroring the gradual reduction in EUA free allowances up to 2034.

Moreover, CBAM leaves producers’ home countries, like China or India, the option to capture the carbon costs at home. Any carbon taxation in the home country can be counted against the CBAM levies.

Yao Li thinks that right around or after 2026 there will be a ramping up of various emission taxation schemes and carbon costs will rise globally. In that sense, the EU will be exporting its decarbonisation policies, which in turn means that other countries, once they tax their own producers, will also have to tax imports eventually. So, companies around the globe will have to become a lot more energy and carbon efficient. There will, of course, be winners and losers, and temporarily at least costs for consumers will rise, but in the long run CBAM, and the copycat schemes it will trigger, will be a major driver for industrial upgrading and fighting climate change.