G7 and the world of net zero [Gas in Transition]

US president Joe Biden embarked on a brief European tour in June, his first overseas trip since taking office. Its importance comes from the opportunity to show that the US is once more under a consensus-seeking president, in sharp contrast with his predecessor Donald Trump.

Biden is also a more climate-friendly president, although he too has to act within the law. While he was in Europe, a US court determined that he had gone too far with his pausing of federal lease sales for oil and gas offshore waters and on public lands – a key revenue source for some states, over a dozen of which had sued. The lease sales may proceed after all, the Interior Department said.

Biden’s visit began with the G7 summit in the UK and continued with his attendance at a NATO meeting in Belgium where Ukraine’s imminent membership was not discussed – despite claims to the contrary by its president Volodymyr Zelenski.

Then it was on to Switzerland to meet Russian president Vladimir Putin whom he has already described as both “a killer” and a “worthy adversary.”

After G7 – trade wars with the EU temporarily set to one side – UK prime minister Boris Johnson drew attention to the need to work together on climate change in order to secure a prosperous future.

Inevitably he flagged the fact that the UK will host the COP 26 Summit late this year. He said: “G7 countries account for 20% of global carbon emissions, and we were clear this weekend that action has to start with us.

“And while it’s fantastic that every one of the G7 countries has pledged to wipe out our contributions to climate change, we need to make sure we’re achieving that as fast as we can and helping developing countries at the same time,” he added. There were no details how this would be achieved and as Equinor’s Energy Perspectives report makes clear, it is aspirational only at the moment.

The joint G7 communique was more pugnacious with its three-pronged critique of China pointing to global tensions once more. It called for a "timely, transparent, expert-led and science-based" study into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. It said China should "respect human rights and fundamental freedoms” in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. And it expressed "serious concern” about the East and South China Seas.

China however did not accept any “interference” in its internal affairs, it said in its sharp response. And a few days later, China and Russia were discussing co-operation in anti-satellite warfare technology.

Norway’s perspectives

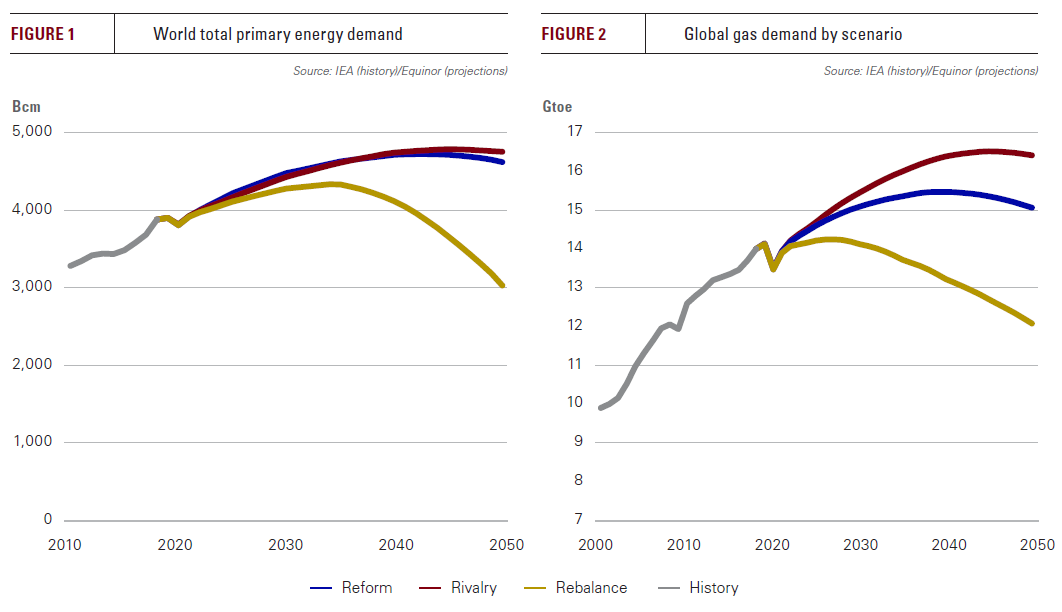

This was the background to the latest edition of the Norwegian energy company Equinor’s Energy Perspectives annual review, which considers three scenarios to understand how the energy mix might evolve over the coming decades and hence the chances of success with global climate ambitions: Reform, Rebalance and Rivalry.

Of the three, Rebalance comes closest to meeting the desired result but is still “far from qualifying as a “net zero by 2050” scenario. It is also the least likely. And as in past years, if for different reasons, Rivalry remains the likeliest but least desirable path.

Reform sees the pursuit of low-cost energy continuing to power economic growth rather than security of supply and the environment, which assures a long-term future for fossil fuels. On the other hand, energy efficiency rises thanks to new technologies. The world grows gradually wealthier as geopolitical tensions ease and emissions gradually fall, but not to the level believed necessary to keep temperatures rising by less than the UN ceiling of 1.5°C.

Rebalance by contrast requires a fundamental readjustment of western values, where the natural environment is also ascribed value. Wealthy nations will have to subordinate their wishes – including dietary and other lifestyle choices – to the needs of the poorer nations. Technology transfer and financing are key to level up the world. It is almost impossible to imagine such docile surrendering, given the eye-watering sums of money involved just to decarbonise energy.

With Rivalry, economic growth and co-operation on climate change take a back seat in favour of energy independence, which becomes the raison d’etre of the energy transition. “There are many indications we are at risk of following this path,” it says.

Trade wars, the neglect of international institutions and anti-globalism are all symptomatic, along with social and political unrest. Economic growth over the period is not only sluggish but it comes at the highest environmental cost relative to the other two scenarios. And emerging economies continue to lag behind.

Equinor, like its European peers, has set a clear ambition to become a net zero energy company by 2050, including emissions from production and final consumption.

It has also set interim targets, including reducing net carbon intensity with 20% by 2030 and 40% by 2035. Equinor also expects to produce less oil and gas as demand falls. By contrast, it will invest in renewables and low carbon solutions and increase the pace of change towards 2030 and 2035, said CEO Anders Opedal June 15.

Equinor’s oil and gas portfolio, important for the government’s sovereign wealth fund, can deliver a free cashflow after tax and investmentsof $45bn/yr from 2021 to 2026, of which the Norwegian assets will account for $4.5bn from now to 2030. New projects coming on stream by 2030 have an average break even below $35/b and less than three years to payback.

Equinor is exiting operated positions in unconventionals and prioritising offshore operations where its strengths lie. Its gross investments in renewables will be around $23bn from 2021 to 2026, and reach an installed capacity of 12-16 GW net to Equinor. But it is adjusting expected project base real returns to 4-8% and remains determined to capturing higher equity returns through project financing and farm downs, like TotalEnergies.

The energy transition represents an opportunity for Equinor to leverage its leading position within carbon management and hydrogen, and to develop and grow new value chains and markets. By 2035, Equinor’s ambition is to develop the capacity to store 15-30mn metric tons of CO2/yr and to provide clean hydrogen in three to five industrial clusters.

Drill, drill, drill

The scramble to produce as much oil and gas as possible before it becomes classed as stranded has led some countries to ease their regulations.

Decisions made lately show governments’ concerns about the acceleration of the energy transition and the mood of some populations that has turned against hydrocarbon production.

Decisions made lately show governments’ concerns about the acceleration of the energy transition and the mood of some populations that has turned against hydrocarbon production.

Not all countries have the same approach – for example Denmark and Ireland have followed the trend towards low-carbon futures with setting deadlines for offshore oil and gas.

But governments of countries that need additional funds to develop infrastructure and grow economically have woken up to the ticking clock of climate change and the implications for financing and for project finance. They had regarded their hydrocarbon resources as money in the bank but that cash bonanza is now at risk.

Three years ago, for example, hydrogen was never looking likely to be a serious competitor with natural gas but now a lot of money is being thrown at it. So the trend gathers momentum.

There is also the rise of renewable energy: costs fall and it brings additional supply security. Some governments can ease up a little on resource nationalism and earn more from exports of hydrocarbons.

Most recently at the end of May the Israeli government increased the allowance for export permits for existing gas fields from 40% to 52% of the resource, with new discoveries being entitled to export all of the gas discovered. In government, only the environment ministry was opposed to this change.

The population generally and the government however see exports as a further guarantor of regional security, as well as a source of taxes. It can be seen as an attempt to avoid stranded gas, even though export routes at the moment are limited to Jordan and Egypt, through the tightly-controlled EMG pipeline.

In the same region, Cyprus is pressuring the Aphrodite field owners, Chevron and Shell, to develop the resource. The field has been held up for several reasons: too small to merit an LNG terminal and too large to supply Cyprus. It therefore needs to be bundled up with other assets to merit a pipeline perhaps to Egypt for liquefaction there.

Shell and Chevron have plenty of experience in devising competition-law compliant joint gas sales agreements and could provide other producers with a route to market perhaps through tolling agreements for LNG capacity.

Turkey is continuing with oil and gas exploration activities, although here energy independence and the ending of sales and purchase contract negotiations is also a motivating factor.

The large gas finds in that sector of the Black Sea have the potential to upset Baku’s plans for the BP-operated Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz field, the starting point of the Southern Gas Corridor.

Elsewhere Norway has granted generous tax breaks for new oil and gas projects approved by the end of 2022. These were dressed up as a response to COVID-19 but they will have beneficial side-effects for the state as well.