Part 1: Fracking to Reduce Risks: Bulgaria and Poland Redefine their Gas Dependency

There are different ways to assess risk in the energy sector. In the broad swath of Eastern Europe this usually means proximity and dependency on Russian controlled gas. When it comes to the new technology of hydraulic fracturing of shale rock deposits, this is usually in terms of environmental impact. Both of these approaches are too narrow.

A panoramic picture of the energy landscape cannot expose pitfalls and fertile areas if both the risk assessment and discussion are narrow. This shifting topology needs to be assessed through a prism that exposes a range of risks that are more than environmental in nature: Fracking may not only increase certain risks, it may also reduce other risks. Thus ‘fracking to reduce risks,’ emerges as a possible outcome to the shale gas revolution from the Baltics to Bulgaria.

This is a two part article that establishes the interconnected risks associated with shale gas in Poland and Bulgaria. Poland is actively encouraging exploration and extraction of shale gas, while Bulgaria has banned fracking. The first article establishes what shale gas offers for each countries’ energy mix. This feeds into the second article’s focus on risk assessment and both the positive and negative consequences of using shale gas to fuel their national economies.

The results presented here draw from a comprehensive risk framework. This was developed to understand the transition to a post-carbon economy, later it was applied to the shale gas sector and published by this author on Natural Gas Europe. This risk typology was recently applied to Poland and Bulgaria in a report for the European Parliament. Citizens and concerned groups from both these countries filed petitions with the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs. A special workshop on shale gas in Europe was held on September 9, 2012 in the European Parliament. This offered the opportunity to assess their concerns while providing a fuller risk assessment of the industry and how the two countries are using or blocking shale gas technologies. Applying the risk framework, elevates the concerns of citizens to a higher policy level enabling their concerns to inform and interact with the national and international policy level debate around shale gas.

The concerns from citizens revolved around institutional, environmental and financial issues (table below). This is a launching pad to address and assess a range of risk important for the public, governments and the gas industry. This author was asked to evaluate the petitions from Bulgaria and Poland. Drawing on 16 interviews conducted in Poland and a diversification assessment of Bulgaria a full report on the short term – contractual risks, and the long term – governance risks, was produced. By using a risk analysis approach to categorize and assess petitioners’ concerns; this elevates petitioners concerns to the broader policy level. This in turn engages with the national and EU level shale gas debate.

| Area |

Classified Petitioners’ Concerns from Bulgaria and Poland |

| Institutional |

Method of issuing concessions (BG & PL) |

|

Redressing of local stakeholders (PL) |

|

|

Issued for concessions for EU Natura 2000 (PL) |

|

| Environmental and Technical |

Destruction of roads and fields (PL) |

|

Monitoring of pipes for corrosion (PL) |

|

|

Use of explosive materials (BG & PL) |

|

|

Borings contain heavy metals and radioactive elements (BG & PL) |

|

|

Storage of borings in unauthorized locations with no oversight or monitoring (PL) |

|

|

Use of illegal poisons and not registering compounds using REACH (BG & PL) |

|

| Financial |

Reduction in economic activity for agro-tourism, farming and forestry (PL) |

|

Payment for water is not enough for the large amount (BG & PL) |

|

|

Higher tax on mineral extraction means higher price for coal and gas for consumers (PL) |

|

|

No legal or financial guarantee from concession holders for ecological or social catastrophe (PL) |

|

| No requirement to carry out land restoration or offer compensation to residents (PL) |

Table 1 Concerns expressed by Bulgarian and Polish Petitioners

Poland: Key drivers

There are three key drivers that are prompting Poland to go for shale gas: Environmental, economic and security of supply. These drivers impact other areas of life in Poland, like the social and political sphere. The fact that five government ministries are involved in advancing shale gas exploration indicates the broad importance to the country. The economic impact is perceived to be substantial: From fuelling a large chemical industry and impacting the price of energy for household and industry. Shale gas is viewed as creating lots of jobs. The broad category of ‘security of supply’ is used by Poles to say, ‘we want less Russian controlled gas.’ In the second part of this article, greater emphasis will be given to the broader set of drivers that fuel the exploration for shale gas in Poland.

Coal-aholics anonymous: The program to cleaner gas

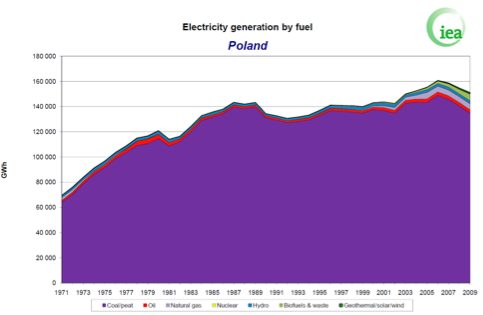

The role that shale gas can play must be framed within the energy paradigm of Poland. The country’s future energy security is based on coal and “going away from coal may result in several serious economic and social consequences for [the] Polish economy.”[i] Ninety percent of electricity produced in Poland comes from coal (chart below). In addition, Poland has twice vetoed the EU Low Carbon Roadmap 2050 and also the EU Energy Roadmap 2050. To say they are anti-low carbon would be inaccurate; rather the country, for a variety of reasons, holds inherent advantages by maintaining a high ‘carb’ diet. The current political, professional and political dialogue in the country holds coal to be a key energy source. The long term decline of coal, out to 2050, for the electricity mix is slight. It is a factual statement to say that Poland is not on the low carbon highway; however shale gas offers the potential to wean a ‘coal-aholic’ country onto a cleaner lifestyle, moving the country further down the road to the EU’s 2050 vision.

Electricity Generation by Fuel Type (Source: IEA 2011ii)

The impact that shale gas can have in the Polish energy mix on reducing GHG emissions is significant. First, compared to imported Russian gas (which currently comprises 70% of Poland’s gas supply), GHG emissions from power plants using domestically-produced shale gas could be 2% - 10% lower. Compared to LNG, shale gas GHG emissions could be 7% - 10% lower.[iii]

Second, heavy reliance on coal to produce 90% of Poland’s electricity, creates and will continue to create significant environmental and economic costs for the country, particularly if ETS allowances will need to be purchased in the third phase of the ETS (or beyond the third phase). The economic impacts, if there is a high price, or large purchases necessary, for these allowances, will be significant with a corresponding rise in electricity prices.

Currently, only 2% of electricity is produced using gas in Poland. According to a recent report produced for the European Commission DG CLIMA, which compared the lifecycle GHG emissions of shale gas and coal in power generation, shale gas has the potential to reduce GHG emissions by 41% - 49%.[iv] For Poland this is more.

Poland’s aging coal fired plants which have a dismal average efficiency of 25%-35%.[v] Compared to lignite coal, the CO2 savings created by using shale gas are 74% - 78%, while compared to hard coal CO2 avoided emissions of 70% -74% may be expected. Using a future power plant efficiency rate of 48% (as assumed in the DG CLIMA[vi] study) CO2 savings using shale gas rather than lignite coal are 59% - 64%, while compared to hard coal savings are 51% - 58%. Shale gas is seen as a viable source of energy for new power plants. For the climate shale gas emerges as a healthier choice.

Projections for the Polish energy mix in 2050 indicate that gas could comprise 20% of the total energy mix, while lignite (the most CO2 intensive source of energy) will still comprise 15% of the energy mix, with the use of renewable energy sources (RES) does not rise above 20%.[vii] The conclusion is that domestically-sourced shale gas (or pipeline gas) significantly reduce Poland’s GHG emissions when compared to current and future methods of electricity production using Polish or imported coal. The replacement of coal by shale gas may assist Poland to getting closer to GHG emission targets contained in the 2050 EU decarbonisation of the power sector (the previously vetoed by the Polish); even if further reduction methods are necessary.

Unionizing against Russian gas and wanting jobs

Recently, on Natural Gas Europe, an opponent of shale gas, who organized a conference in the Poland, wrote, “Defending the shale business ventures of publicly traded companies like Chevron and PGNiG makes us think that Polish unions like Solidarnosc have strayed far from their roots!” The answer in short, is no. The union understands the economic benefits through jobs and the role that shale gas place in the country’s energy security of supply – with 70% of supplies controlled by Gazprom. Solidarnosc opposed the brutal Polish Communists backed by the USSR. The use of shale gas seems to fit well with the movement’s roots. As one interviewee stated, “it is always the younger brother that gets beat up, and Poland is the younger brother.” Historical relations (and economic) would indicate the need to diversify gas supplies. Union support for shale gas emphasizes the economic impact that a viable shale gas industry offers the county. However, this is only the case if it happens; we are still in the theoretical development stage of the industry with only a few dozen test wells drilled.

The broader economic impact is assessed in a study sponsored by PKN Orlean and carried out by the CASE Scientific Foundation.[viii] Three different growth scenarios are developed for the shale gas sector: 1) moderate, 2) increased foreign investment, and 3) accelerated growth. The projection ranging out to 2025 foresees 27,000 direct jobs created in the accelerated scenario and 483,000 indirect jobs created. However, this would require the drilling of 305 wells annually and annual investment of USD 3.5 to 4 billion. This is all extremely optimistic at this point based on the minimum amount of wells drilled and the operating speed of both companies and the Polish government.

Bulgaria

Location, location and Russia: The key elements of energy security in Eastern Europe. The most significant energy event – of modern times, is the January 2009 dispute over gas between Russia and the Ukraine. This culminated in the cutting of gas supplies to Europe for 22 days. The cessation by Gazprom of the gas supply for Ukrainian consumption started on January 1, 2009 and then the Ukraine diverted the ‘off-take’ gas supplies destined for Europe; resulting in complete termination of supplies to Europe – and Bulgaria, on January 7, 2009.

The cut-off of gas significantly affected Bulgaria. Gas was 100% cut off for 13 days to Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia in the midst of a cold winter. These countries held limited or no reserves, underscoring both the severity of the dispute and the lack of infrastructure and preparedness. Despite the impact on Bulgaria, the country has moved at a snail’s pace to build diversification routes. The near total reliance on Russia for gas deliveries means finding and utilizing other sources of gas should (logically) be a priority.

The Bulgarian parliament in January 2012 overwhelmingly rejected the use of shale gas technology by imposing a moratorium on exploration and extraction using hydraulic fracturing. This decision was based on environmental grounds. One company, Chevron, held an exploration license and was impacted by this reversal. This is despite the fact that Bulgaria might be sitting on a huge pile of shale that could fuel the country with gas for hundreds of years. However, there exist other options that may mean Bulgaria will soon be at the intersection of a European gas highway.

Gas supply diversification options

There are four diversification options available for Bulgaria. This may mean shale gas does not have to be a diversification option. Although, domestically sourced gas is an extremely secure source of energy, that may be viable if extracted. However, the plethora of options may make it uneconomic to extract in the future. The four options are as follows:

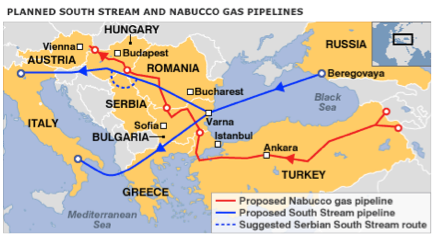

First, there are two long distant gas pipeline proposals which could run through Bulgaria: Nabucco West and South Stream (Map 4). Nabucco West is composed of a consortium of European oil and gas companies. The updated route for Nabucco West will bring gas from the Caspian Sea to Austria (it will arrive to Bulgaria overland from Turkey). Nabucco West (if built) will largely rely on Bulgaria’s existing gas network to move gas through the country and make it available for domestic consumption. A decision will be made in 2013 whether Nabucco West will go ahead. The ‘other’ pipeline, South Stream is backed by Russia, and also has European partners, Eni, EDF and Wintershall, it will be laid under the Black Sea from Russia and will come onshore in Bulgaria.

Nabucco and South Stream gas Pipeline Routes (Source: BBC[ix])

Second, more gas can come from boosting gas network interconnectors to Bulgaria’s neighbors and throughout the Southeast European region. New interconnectors with Romania and Greece are either under construction or planned. This will enable Bulgaria to weather any supply disruptions such as the 2009 event. Gas storage has also been increased in Bulgaria, smoothing any likely supply disruptions. The increased interconnector capacity can assist Bulgaria to diversify its gas supply.

Third, LNG terminals planned in Croatia and the proposed AGRI LNG project that may transport gas across the Black Sea from Azerbaijan to Romania could increase supplies to Bulgaria – if ever built.

Fourth, domestic off-shore production could take place from Bulgaria’s continental shelf. Initial tests indicate that large quantities of gas could be extracted and be sufficient to provide the country with 25 – 30 years of independent gas supplies. A concession has been awarded to a consortium of Total, OMV and Repsol for gas and oil exploration.[x] However, reaching the gas is technically challenging as it is at a depth of 5,000 meters. Strong environmental arguments (if environmental reasons are the true cause of Bulgaria’s rejection of shale gas) could be made against extraction of this.

Bulgaria’s ability to diversify away from its significant dependence on Russia may become a reality over the course of the next 10 years due to one or more of these potential gas projects. Shale gas can become a reality, but as will be discussed in the next article of this series, overcoming the entry barriers may be harder in Bulgaria than in Poland.

Conclusion

Energy dependency comes in many forms: From over reliance on one type of fuel to having only one supplier. Breaking free from this dependency takes time and forethought. Poland’s addiction to coal means a long-term strategy needs to be implemented – going cold turkey like the Germans did with nuclear power is not an option. The general mindset within the country is a gradual reduction and leveling off of coal in the energy mix. This allows a space to open up to gas and renewable energy as replacements. If this is to be the case then Russian gas dependency must be addressed. As will be explored in the second part of this article, the broad risks, including benefits, associated with shale gas in Poland hold it as a viable fuel that is ripe to fulfill an important role. Bulgaria, while rejecting shale gas outright, and highly dependent on Russia’s Gazprom – holds long term options for diversification. Whether one transit pipeline or two are built, does not matter for greater security of supply. But what does matter is competition and diversification away from Russia for achieving a lower price for gas.

Greater competition between sources of gas, for both Poland and Bulgaria will make a difference. The often cited high price of Russian controlled gas can only be tackled by diversification away from the Russian monopolistic position. In this camp, both countries sit. Therefore, assessing not only the environmental risks associated with the shale gas option is important, but as the second article of this series will explore, broader economic, political and social risks need to be assessed to see whether shale gas serves as the anti-monopolistic (Russian) option. The potential of lower priced gas (with a high economic impact factor) and domestically sourced (high security impact) offers the potential to mitigate a broad range of risks. Eastern Europe is not entering a period of constrained energy resources; rather it is now breaking free of the legacy energy infrastructure of the Communist era. Poland may consciously resist the road to a low carbon economy by 2050, but just as the US has, they may just stumble down the low carbon road while being weaned off coal.

Michael LaBelle is an Assistant Professor at the Central European University Business School and in the CEU Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy. He teaches courses on sustainability in business and on energy technologies and policies. He conducts research on how institutions and organizations foster change to contribute to a low carbon future. His blog is energyscee.com.

[i] Jozef Dubinski, Future of Coal as an Energy Fuel (Kyrnica-Zdroj, Poland, September 3, 2012).

[ii] International Energy Agency, “Electricity Generation by Fuel”, 2011, http://www.iea.org/stats/pdf_graphs/PLELEC.pdf.

[iii] AEA Technology, Climate Impact of Potential Shale Gas Production in the EU (European Commission DG CLIMA, July 30, 2012), 67, http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eccp/docs/120815_final_report_en.pdf.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Earth on the crossroads (Energetyka Konwencjonalna), Conventional Energy (Ziemia Na Rozdrożu), 2008, http://ziemianarozdrozu.pl/encyklopedia/51/energetyka-konwencjonalna.

[vi] AEA Technology, Climate Impact of Potential Shale Gas Production in the EU.

[vii] Władysław Mielczarski, “Prognozy Produkcji Energii Elektrycznej i Zużycia Paliw” (presented at the Economic Forum, Kyrnica-Zdroj, Poland, September 4, 2012).

[viii] Adam B. Czyzewski, Eduard Bodnari, and Grzegorz Kozieja, Gas (R)Evolution in Poland: Which Way to Success? (PKN Orlen, 2012).

[ix] “Gazprom to Control Serbia’s Oil,” BBC, December 24, 2008, sec. Europe, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7799396.stm.

[x] Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency, “Black Sea Natural Gas to Make Bulgaria Energy Independent: Black Sea Natural Gas to Make Bulgaria Energy Independent -”, September 2, 2012, http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=142861.