Finding Gas in the Caspian Sea [NGW Magazine]

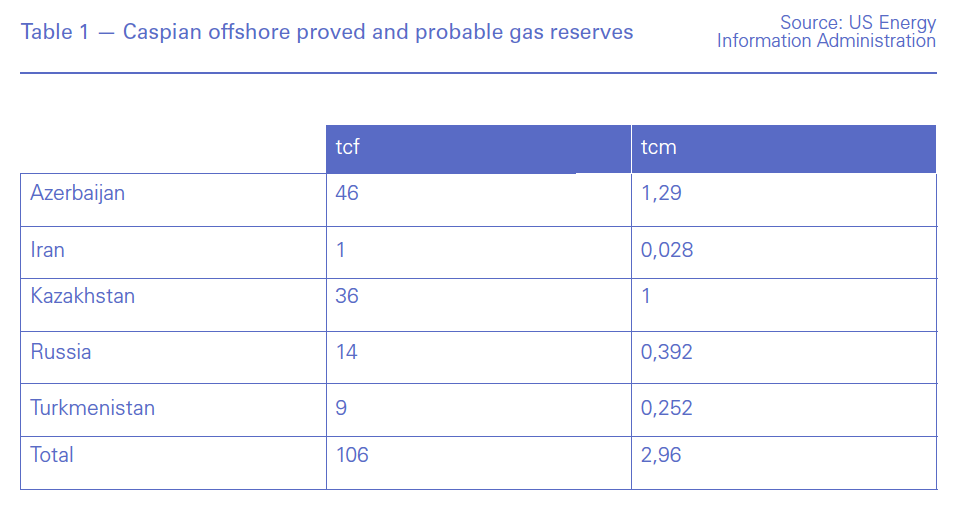

The Caspian Sea is primarily known for its large oil rather than natural gas resources. But with an estimated 3 trillion m3 in proven and probable resources, according to the EIA, the area’s gas potential is still considerable in its own right. The sea’s five littoral states – Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkmenistan – have had varying degrees of success in exploiting this wealth.

With the help of BP and other foreign investors, Azerbaijan was able to develop the more than 1 trillion m3 of gas at the offshore Shah Deniz field, and earn revenues from the export of these supplies.

With the completion of the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) next year, gas from Shah Deniz and other Azeri fields will reach markets as far west as Italy. Kazakhstan too has been able to use associated gas at its Kashagan oil project for re-injection and domestic sales.

Russia, however, despite having sizeable offshore gas fields of its own, has largely left these resources untapped. Turkmenistan has also had limited success in monetising its Caspian gas.

Russia

Russia’s share of Caspian Sea resources, while paling in comparison to those found in its neighbours’ waters, are still substantial, estimated by the IEA at close to 400bn m3 proven and probable. Exploration and development off the Russian coast has been spearheaded by Lukoil, the country’s leading private oil and gas company.

The company began a state-backed seismic and drilling campaign in the Caspian in the late 1990s, and within just over ten years, it had identified six commercially-sized oil and gas deposits. The Korchagin, Rakushechnoye and Filanovsky fields were found to be mostly oil, while the Khvalynskoye, 170 km and Kuvykin fields were assessed to hold mainly gas.

Lukoil quickly began work developing the oilfields, bringing on stream Korchagin in 2010 and Filanovsky in 2016. Rakushechnoye is due to enter production in 2023, following a final investment decision (FID) taken last year. While the company has so far prioritised the Caspian’s oil, it is starting to look more seriously at options for its gas as well.

In documents last year, Lukoil said it did not expect to commission the 322bn m3 Kuvykin field until 2026, but in April, company CEO Vagit Alekperov suggested an earlier launch date of 2022-2023 in a meeting with the Russian president Vladimir Putin. While an FID has not yet been reached, Lukoil also hired an international engineering firm in May to prepare project designs, an industry source told NGW. Production is expected to plateau at 6.6bn m3/yr, according to past statements by Alekperov.

In contrast, Lukoil is yet to shore up plans to exploit either Khvalynskoye or 170 km, stating last year it did not expect them to start producing before 2030. Khvalynskoye holds some 332bn m3 in recoverable gas, while 170 km’s resources have not been revealed.

There are several reasons why Lukoil has taken a slower approach to these projects. The Caspian presents a number of operational challenges that can weaken margins. Geologically, reservoirs are often deep with greatly varying characteristics and prone to high temperatures and high pressure. Water levels fluctuate significantly depending on seasons, and in winter, large parts of the northern Russian zone freeze over and then melt quickly in spring, with fast-flowing ice drifts posing a risk to infrastructure.

In the case of Lukoil’s gas projects, margins are potentially weakened further by the fact that only Russia’s state-owned Gazprom can export gas via pipeline. As such, Lukoil must either sell its gas to Gazprom, find buyers in the fiercely competitive market of industrial gas users, or find another means to add value to its production.

Prompted by 2012 anti-flaring controls, Lukoil has invested in onshore petrochemical production and power generation to utilise the associated gas produced at its Caspian oilfields. With a number of other Russian oil and gas producers advancing petrochemical projects at the moment, the company does not feel this is a viable option for its offshore gas fields, industry sources said.

The sources said Gazprom had expressed its interest in the past in taking stakes in some of these projects, in return for exporting Lukoil’s share of future production on its behalf. Gazprom proposed buying Lukoil’s share at a “more reasonable” price than it would otherwise receive under this arrangement, they said, although no serious discussions have taken place between the pair.

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan has the smallest share of the Caspian’s gas, but it is still sizeable, being assessed at around 255bn m3.

The country has struggled to exploit this gas for the same reason it has struggled to exploit offshore oil: aspects of its authoritarian political system and state-managed economy have posed barriers to foreign investment, and it is not interested in exporting gas in its own name.

Despite authorities offering international oil and gas companies 32 offshore blocks over the years, there are currently only two active projects in the Turkmen Caspian – Block 1 operated by Malaysia’s Petronas and Block 2 managed by UAE-based Dragon Oil.

Several other players have attempted to explore the zone in the past, such as Denmark’s Maersk – now Total – and Germany’s Wintershall Dea, but gave up for various reasons. Cyprus-registered Buried Hill operates a mainly oil-focused project in waters disputed by Azerbaijan, but is not undertaking any activity there.

So far, only Petronas has found a means of monetising its gas, having entered into an agreement to sell some volumes to Turkmenistan’s national gas group Turkmengaz. As Turkmenistan maintains a monopoly over exports of gas, this is the only option available to international producers in the country. But Turkmengaz has limited need for extra gas at present, as the company already has enough production of its own to satisfy local demand and overseas orders.

Turkmenistan has held talks with Azerbaijan on the supply of some of Petronas’ gas to the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli (ACG) oil project via a new pipeline. This represents a scale-downed version of the long-delayed Trans-Caspian gas project, which has gone nowhere in the two decades since Shell and Bechtel planned to build a pipeline. But talks on the plan have frozen, industry sources said, and a preliminary agreement expected to be reached at the Caspian Economic Forum in August did not materialise.