Europe absorbs winter risks [NGW Magazine]

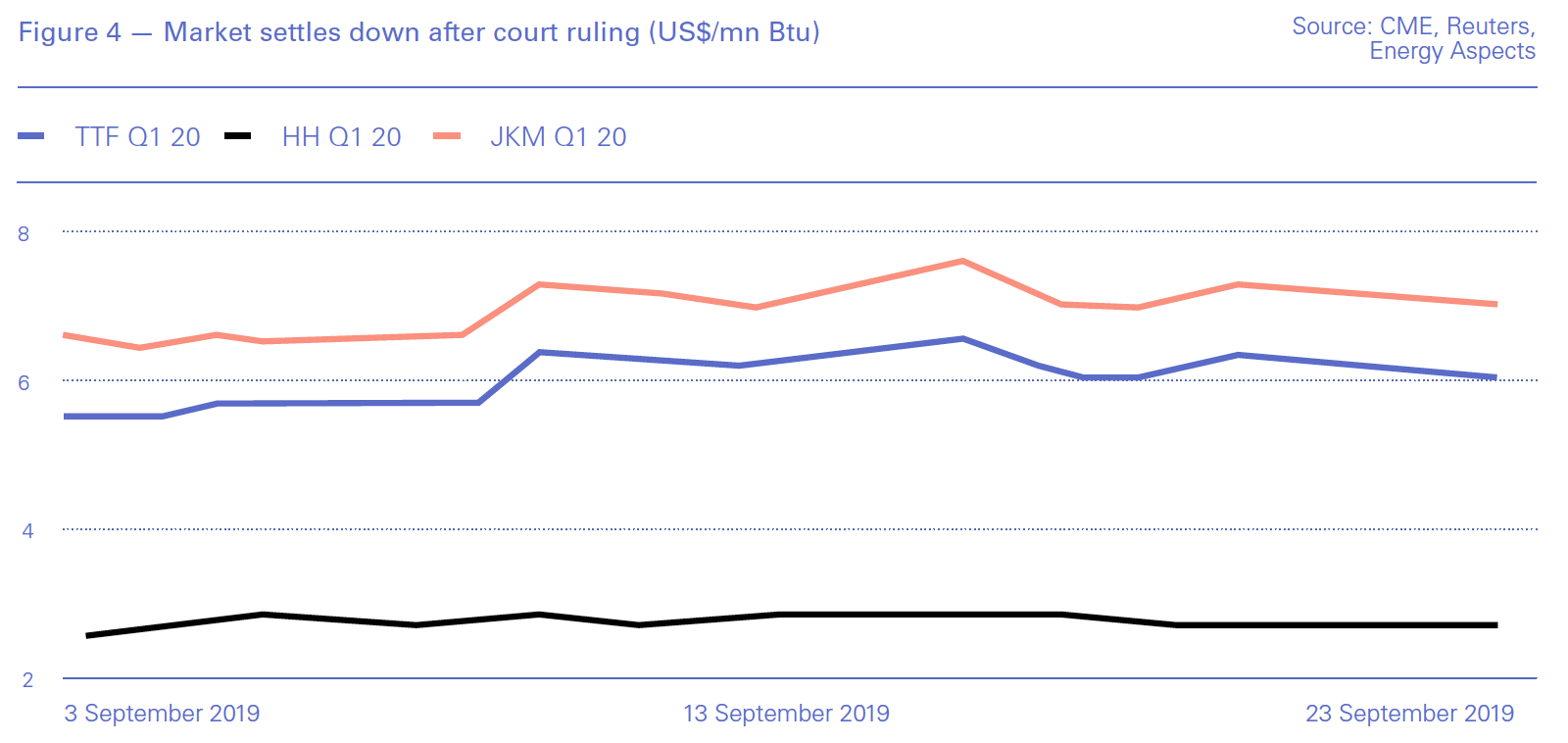

The coming winter will be a test of the reliability and affordability of LNG supplies to Europe, as pipeline deliveries look less certain than they did this time last year. But the market seems to have taken in its stride the doubts around Ukraine transit, lower Dutch gas output and the risk of high oil prices – exemplified by the dramatic attack on Saudi Aramco’s biggest facilities.

Since the end of winter – a mild one, compared with last year’s ‘beast from the east’ – the market has been acting as expected: traders have hoovered up cheap gas for injection into storage to enjoy the higher prices next winter.

With September not yet over, the facilities across Europe are over 95% full on average and those in Ukraine are over two-thirds full: it is likely to begin the withdrawal season with comfortably more than 20bn m³ stored.

But storage is not spread evenly: the UK has almost none now, for example. Still the UK’s biggest household supplier, Centrica, which operates Rough, now uses the former 3.5bn m³ facility as a producing field, the ageing compression machinery not thought worth repairing. As its planned, if not expected, departure date from the European Union looms, the UK is relying on pipelines from Europe and LNG for the peak day therm, on top of its own output.

And the growing amount of US LNG coming to market priced against the low Henry Hub market is blowing away the cobwebs at the historically under-used regasification terminals, as Asia cannot take it all. It will take very long, cold winter to erode the oversupply, says Poten, forecasting a healthy surplus of gas in one form or another for another year.

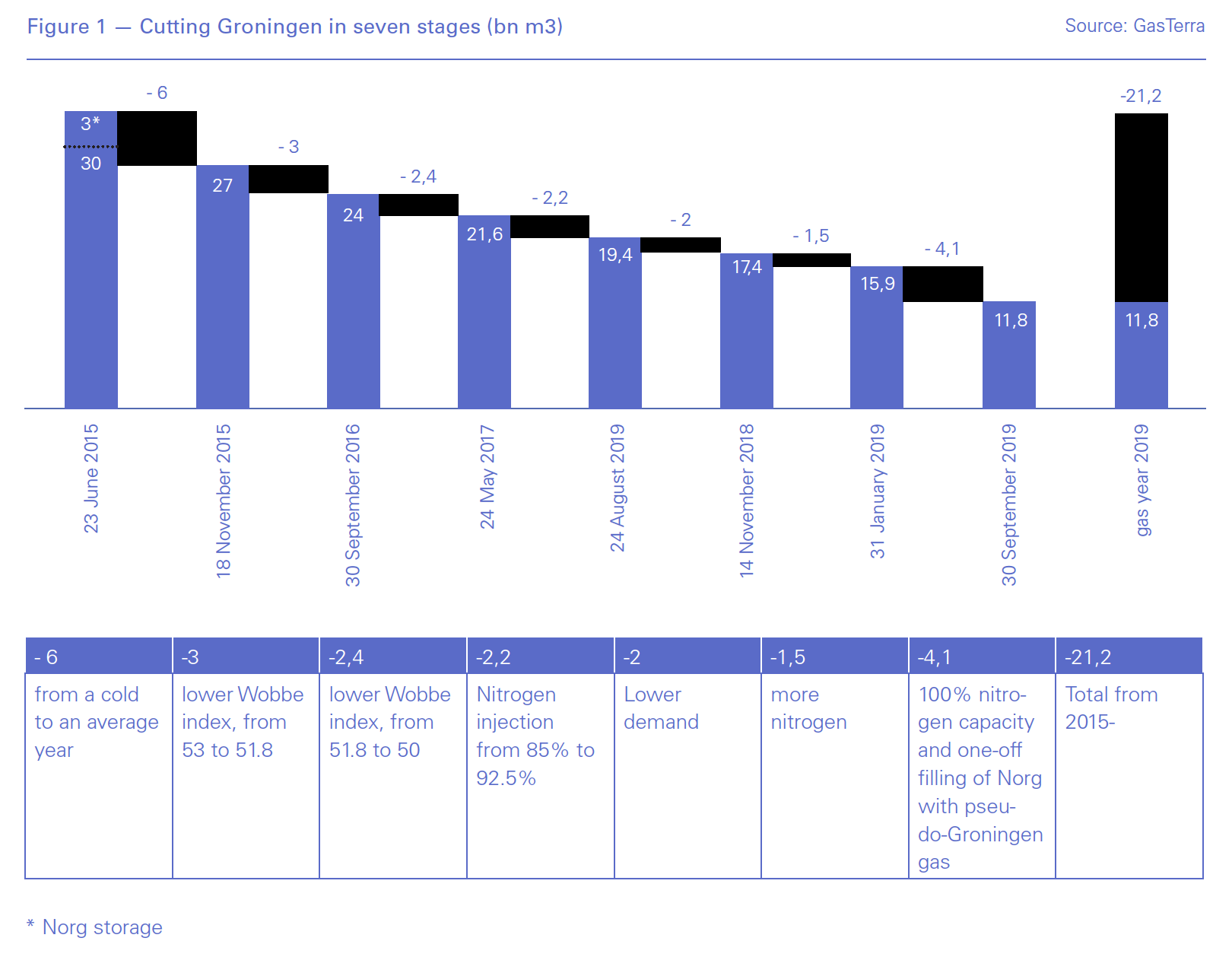

But it is not all positive for consumers. Across the North Sea in the Netherlands output from its biggest gas field Groningen is to be brought even lower than the recommended minimum of 12bn m³ for the 2019-2020 gas year. To the surprise of the market, the government has found ways to manage with just 11.8bn m³, following a rebuke from the Council of State saying that the economy ministry had to work harder to lower its 12.8bn m³ plan for the year, itself a big reduction from last year (see graph).

What was even less expected was that the government is planning to close it not in 2030, as its previous guidance said, but perhaps in the middle of 2022. NAM-operated Norg storage can act as a proxy for Groningen, taking in nitrogen rich gas in spring and summer for winter use.

That assumes among other things that the 5bn m³ Norg plant can be filled with pseudo Groningen gas on a long-term basis, minister Eric Wiebes wrote to parliament September 10. It can be expanded too, to 6bn m3. But that does not mean Groningen can be closed in 2022. Wiebes said the possibility cannot be excluded that gas production will continue to be necessary beyond 2022, for instance to meet the sharply increased demand for gas of a cold day in winter. “Based on [transporter] GTS advice, a full shutdown of the field is expected to feasible by 2026 at the latest, and possibly earlier. Together with [subsoil regulator] SodM, GTS and NAM, I will examine what a realistic date for the shutdown would be over next few months,” he said.

Regarding exports of low-calorie gas to Germany and Belgium, those countries’ national network operators have agreed to scale back those to zero up to September 2029. GTS said in July that the reduction abroad is progressing as scheduled.

Cutting gas production to 11.8bn m3 will cost €400mn, which has been included in the Budget Memorandum 2020.

Choices facing the government include: keeping the field under NAM’s operatorship post-2022 for very cold winters or to offset transit failure through Ukraine, on some fee-based arrangement; keeping the field operational but in the hands of the state EBN, paying off Shell and ExxonMobil; and winding the field down completely, with NAM responsible for decommissioning.

This would leave the Netherlands reliant on the small fields and otherwise at the mercy of LNG markets and Russia, putting it in the same basket as many of its neighbours, from a supply security point of view. It is not a coincidence that the Balgzand-Bacton Line is from this summer practically a Bacton-Balgzand Line too.

NAM will have to be compensated for the early closure of Groningen and the significantly lower revenues from the field. In order to discontinue gas production as soon as possible, additional agreements with Shell and ExxonMobil about the deployment of Norg are necessary, for which under an interim agreement, a provisional amount of €90mn has been agreed.

Despite the total replacement of genuine Groningen with pseudo-Groningen gas, the economy minister still wants the nine largest industrial users to convert to high calorie gas, according to major users group VEMW. Pipeline operator GTS told the minister that the conversion projects make insufficient contributions to justify the associated investments. In his letter to the House of Representatives, the minister seems to overrule this advice by sticking to his bill that prohibits the largest nine customers from still using low-calorific gas after October 1, 2022, said VEMW.

As an aside, it is noteworthy that for the Dutch, where there has been some damage to housing, production can continue unless tremors in the region of Groningen reach 3 on the Richter scale, despite the damage done to buildings. The UK, which could by now be looking forward to a rebound in gas production, has halted Cuadrilla’s activity again, while it investigates an exceptional tremor of 2.9 on the scale.

Denmark’s gas mix is also set for major changes, following the closure this month of the offshore Tyra field. Tyra has been the backbone of Danish gas supply for decades, typically accounting for around 90% of national production, which came to 4.3bn m3 last year. But over the years its platforms have subsidised, requiring its Total-led operating consortium to fork out $3.2bn on a three-year redevelopment programme.

Denmark currently produces more gas than it consumes, but until Tyra’s restart in July 2022, it will have to rely on imports from Germany to cover demand. In practice, this means Denmark will be mostly acquiring Russian gas arriving via the Nord Stream. Output reductions in Denmark and the Netherlands will have a knock-on effect on Germany, Europe’s biggest gas consumer, which counts the two countries among its main suppliers. Germany will likely fill this gap with extra Russian volumes and LNG.

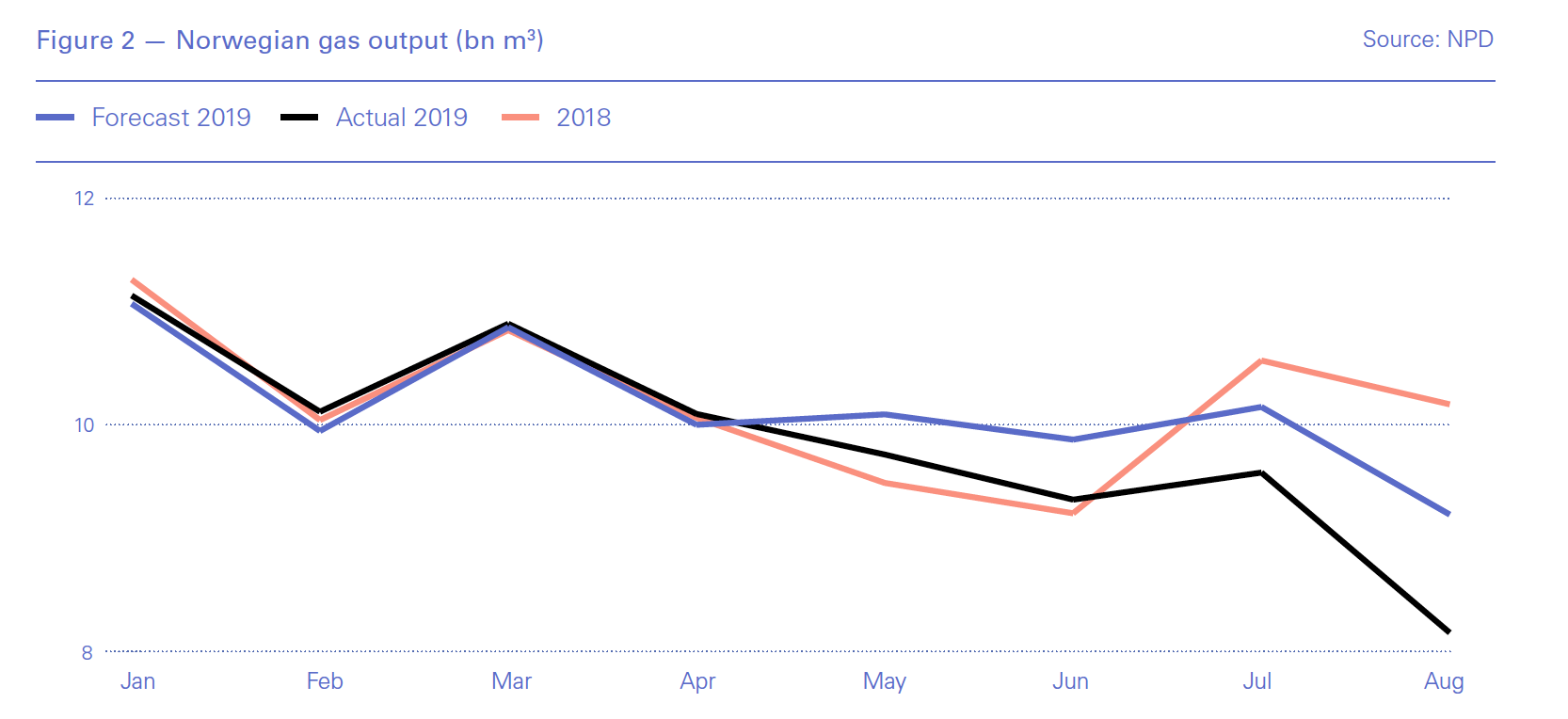

Nor can Europe’s second largest exporter, Norway, be counted on to meet shortfalls, as technical problems offshore this year have hit supplies. This has led to a drop in output for four months running, compared with the forecast (see graph). Oil output is also lower, but while the giant Johan Sverdrup will correct that directionally when it comes on stream next month, there is practically no gas in that field.

Court ruling ‘preposterous’

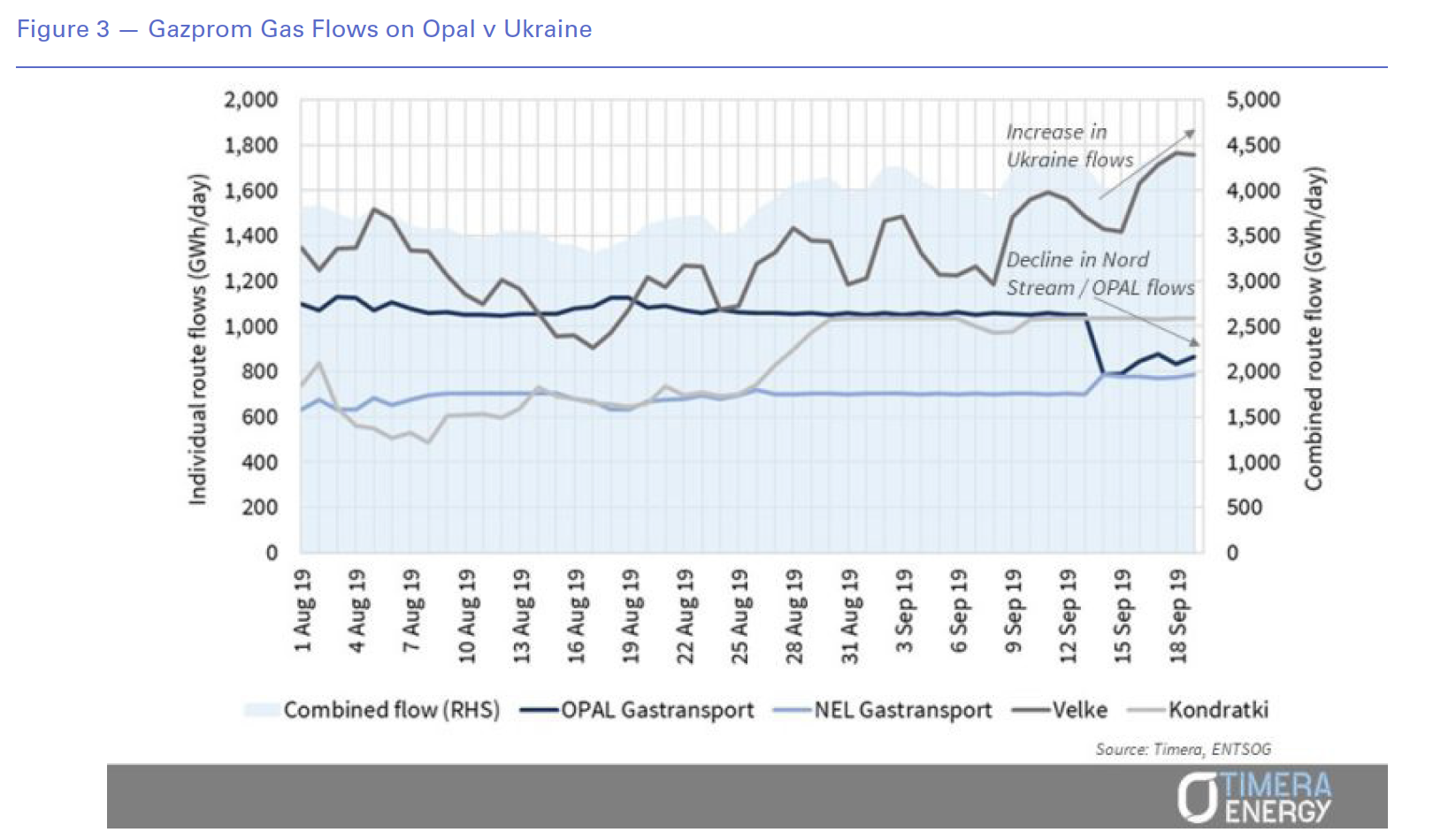

The second surprise development was the European Court of Justice’s ruling which overturned the European Commission’s decision to accept the German network’s regulator’s judgement to allow Gazprom to use all the capacity it had in the Opal line: 40% of 36bn m³/yr. At time of press it does not seem as if the ruling will be challenged.

Poland, which was joined also by Lithuania, Latvia and Naftogaz Ukrainy in its suit, said that EU energy legislation is designed to prevent the monopolisation of access to gas pipelines within the Community. “We are glad that the Court of Justice of the European Union has clearly affirmed that EU legislation applies equally to all, including Gazprom,” said the dominant, state-owned gas company PGNiG.

Gas Value Chain founder and consultant Wolfgang Peters, who had not read the ruling in full, told NGW that he found the ruling “preposterous, particularly if the flaw found was that the EC did not take into consideration Poland’s security of supply. We all know that Poland is misrepresenting their alleged dependency and is absolutely not affected by Opal flows. It was therefore justifiable (although not smart) to keep Poland out of the considerations for the EC's decision.

“In any event, the perceived 'flaw' in the EC's decision-making process could be mended by now including Poland into its considerations.

“Will the EC do that, given the anti-Russian sentiment in Brussels? They may, given that there is still a big risk that Ukrainian transit lapses on December 31, 2019, in which case having only half of NordStream 1 volumes might exacerbate the potential shortfall.”

PGNiG had not responded to NGW’s request for comments on these aspects of the ruling at time of press.

Switch of flows

Threatened with fines if it ignored the ruling, Gazprom switched flows to Ukraine from Opal, also meaning less gas flowing through Nord Stream, its offshore route. This led to a rise in forward prices.

This would not matter so much if relations between Ukraine and Russia had normalised, but Gazprom still owes Ukraine the award – a few billion dollars with interest steadily mounting – ordered by the Stockholm arbitration court in February 2018. And there is no contract covering transit from January 1, 2020, which will be regulated by European Union network codes – and Ukraine is still an important transit route, even when Nord Stream is running at full capacity, and a big earner for Kiev.

Nord Stream 2 is unlikely to be ready by January 1, as the Switzerland-based company building it still has not had approval from Denmark for the route across its waters. It has left that section till last, accordingly, but it has given no guidance when it expects to complete the line, pressure it up with gas and commission it.

Faced with the loss of sales, Gazprom is co-operating with the Ukrainian adoption of European Union gas capacity rules. As a major trader and supplier in Europe, it is familiar with the process. That could be to Gazprom’s advantage, as capacity is available for a range of periods, including just for day-ahead which Gazprom could book until Nord Stream 2 comes online. The tariff could be low as the pipelines are many decades old and so have covered their costs, although it must cover at least the transporters’ fuel costs.

Naftogaz, speaking after the trilateral meeting in Brussels September 19, said: “Gazprom has for the first time accepted the possibility of working in line with European rules from January1, 2020 if they are fully implemented in Ukraine by the end of this year.”

In the past Gazprom has not booked capacity by the rulebook, according to Ukraine. This has sometimes forced Naftogaz to counteract unexpectedly low deliveries of gas at its eastern border overnight, while seamlessly maintaining a steady outflow at the exit points at its western borders. This has placed stresses on the infrastructure.

For the European Union’s commissioner for the energy union Maros Sefcovic, Gazprom’s acceptance of EU rules was the most important outcome of the mid-September meeting. He said: “Both sides have agreed in principle that a future contract will be based on the EU law. We have clearly described to the Russian side that Ukraine is gradually implementing EU energy rules and a future contract must respect them.”

More good news was the “clear progress” on unbundling Naftogaz. The Ukrainian government had made this its priority, Sefcovic said. The publication of the roadmap the day before the meeting “paves the way for a fully unbundled independent transmission system operator to be established – and certified according to the EU law – by the end of this year.” And “concerning the duration of a future contract, volumes and the tariffs setting, we have had a convergence of minds.”

Naftogaz said the new unbundling model will ensure the independence of the new operator and the complete separation of the activities of transport from production and supply, which is the final goal of unbundling. It will need a new law and a series of other practical steps enabling the completion of the process by year end.

The gas transmission system operator will be sold to Magistralnye Gazoprovody Ukrainy, a state-owned company independent from Naftogaz. It will be controlled by the finance ministry while Naftogaz reports directly to the cabinet of ministers, which suggests a close relationship at least until one or the other is sold off.

The next meeting, involving the energy ministers of Ukraine and Russia, will take place by late October, Sefcovic said, “when, I hope, we will have more progress on the remaining issues. We will remain in contact in the meantime. With Ukraine, we will work closely on the unbundling and certification process as well as on the transposition of EU legislation into the Ukrainian law.”

Whether or not he will be representing the EC thereafter “depends on the outcome of the meeting that should take place in October and on the next president of the Commission,” his spokesperson told NGW.