Europe’s just transition: the politics of change [NGW Magazine]

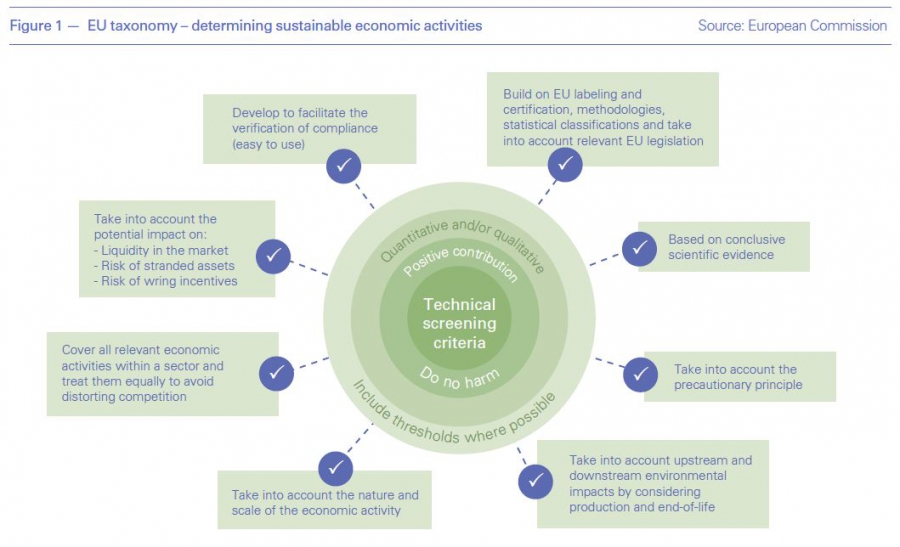

EU’s Taxonomy regulation is intended to “provide clarity and transparency on environmental sustainability to investors, financial institutions, companies and issuers thereby enabling informed decision-making in order to foster investments in environmentally sustainable activities” (Figure 1). It is the world’s first green list for sustainable investment.

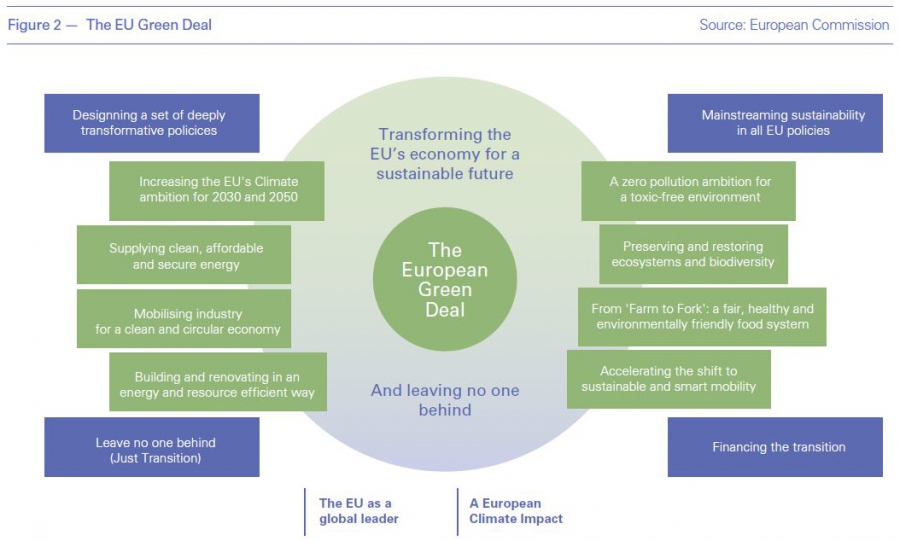

Finding the right balance between what is considered to be green and what is not is critical to achieving a successful energy transition in Europe. But there is a danger that Taxonomy definitions could have a counter-productive effect on related EU policy emanating from the Green Deal (Figure 2).

An increasing problem is that activism in Brussels has gone so far that it is in danger of blocking rational arguments, becoming dogmatic rather than rational. A kind of witch-hunt is developing, where the oil and gas sector is the witch. A headline mid-February in a Brussels publication ‘exclusively revealed’ that three EC top officials – Josep Borrell, Stella Kyriakides and Adina Valean – had previouslybeen linked to the ‘fossil fuel’ industry. As the article implies, they are tainted!

This is a sad, but also worrying, state of affairs. According to all credible outlooks, oil and gas will still be part of Europe’s energy mix over the next 20 to 30 years. Until other energy forms are available to replace them reliably and affordably, they will be part of energy transition. As such they will be essential to Europe’s security of energy supplies.

This is what has led to a challenge to EU’s draft Taxonomy rules by a group of ten central, east and southeast European countries that includes Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia, with Poland being particularly vocal.

Their key complaint is that natural gas has not been granted transition fuel status in the guidelines. In addition to these ten countries, there is also stiff opposition from the natural gas, bioenergy and forestry industries.

EU member state challenge

The challenge mounted by the ten European countries was preceded by a letter in May 2020 entitled ‘The role of natural gas in a climate-neutral Europe.’ At that stage, Cyprus and Malta were not included. It made the case for natural gas as a transition fuel replacing coal in power generation, arguing that “when replacing solid fossil fuels, natural gas and other gaseous fuels such as bio-methane and decarbonised gases can reduce emissions significantly.” They added that “In the years to come, renewable and decarbonised gases will gradually replace natural gas, creating new opportunities for the industrial and energy sectors and reducing risks of a lock-in effect.”

What has not been addressed satisfactorily, if at all, by the EC’s technical expert group is that these countries have different starting points, and limited resources to exit from fossil fuels, making energy transition a challenge, requiring time and funding.

They emphasised the crucial importance of maintaining EU support and financial assistance for the development of gas infrastructure during transition through structural funds and investment loans. But, under pressure from climate campaigners, the EC appears to have largely ignored their request in the November publication of the Taxonomy rules.

With Cyprus and Malta bringing the total to ten, not surprisingly they have now come back more strongly, insisting that their demands are taken up by the EC more seriously.

The latest is the ten countries’ ‘working non-paper’ 18 December, following closure of the consultation period.

The key issues were raised at the EU summit in December, where after heated arguments the EU leaders acknowledged the right of each country “to decide on its own energy mix and to choose the most appropriate technologies to achieve collectively the 2030 climate target, including transitional technologies such as gas.”

The ten cite this in defence of their claim that their demands are “in line with the conclusions of the December European Council.”

As a result of this challenge, the EU has been forced to delay publication of the detailed taxonomy implementation rules. But it is more than just a challenge. Without change, that is, granting natural gas a transition-fuel status, the ten EU member states are threatening blockage of the new rules.

The EU is putting a brave face on things, with Daniel Sheridan Ferrie, the European Commission’s spokesperson for banking, financial services, taxation and customs, saying that “colleagues are currently assessing the volume and nature of feedback,” but refusing to indicate a new publication date. However, late April appears to be likely.

The plan is that the Taxonomy text is adopted by MEPs and EU governments some time in 2021 and come into force from 2022.

Responding to a question by NGW on why Greece co-signed this letter, Costis Stambolis, chairman and executive director of Institute of Energy for South-East Europe (IENE) and member of Greece’s National Committee for Energy and Climate Change, said: “Greece along with the other governments who signed the letter need to advance their plans for further natural gas use which they will need for power generation – and base-load for that – as they will be retiring a considerable number of coal/lignite power plants over the next five years. There is no other fuel which can immediately substitute coal fast enough and reliably. RES are intermittent and as they grow in capacity they need storage and base-load which takes many years to develop.” He added that “also gas needs to be used further for commercial and domestic uses, through grid expansion, as it will be replacing oil which is used on a large scale for fuelling space central heating systems.”

Other challenges

On October 19, 57 industry leaders, including BP, Equinor, Total, Repsol and PGE Poland as well as major industry groups Eurogas, IGU and IOGP called in a letter to the EC president, Ursula von der Leyen, for natural, renewable and decarbonised gases, along with carbon capture utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies, to be recognised as part of the energy transition towards a carbon neutral economy in 2050.

They want the EC to support ambitious and pragmatic policy tools and highlight the key role that gas plays in balancing variable renewables at an affordable cost, reducing CO2 emissions and guaranteeing system reliability.

Key to this is the emissions threshold to allow natural gas to be part of the energy transition phase. At present this is not the case with the EC sustainable finance threshold set at 100g CO2/kWh. Even the most efficient natural gas-fired power plants only manage about 350g CO2/kWh, while the kind of plant needed to balance renewable energy, the rapid-start sets of 10-MW reciprocating engines of the kind utilities buy, are very inefficient. To add to the confusion the limit adopted by EIB for funding projects after 2021 is 250g CO2/kWh and the threshold in the ‘Do-No-Significant-Harm’ (DNSH) criterion is 270g CO2/kWh.

The EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will make €672.5bn available for projects that fit with the DNSH guidance. It aims to support member states in ensuring that all investments and reforms they propose to be financed by the RRF do no significant harm to the EU’s environmental objectives.

Should the current EC threshold remain, new natural gas-fired power plants will no longer have any place in the European power mix. Nevertheless the two very different thresholds proposed by the EC and EIB introduce confusion and loopholes. A power plant with a fuel mix comprising 20% hydrogen and 80% natural gas would satisfy EIB and DNSH, but not the EC.

In effect the letter by the ten states asks the EC to modify the taxonomy so that EU financing mechanisms can support the replacement of coal with natural gas as a transitional solution to bridge the technological gap.

There is also strong opposition mounted by the bioenergy, forestry – supported by Scandinavian countries – and nuclear industries.

The taxonomy is also being challenged by other EU states. In Germany, a study “concluded that only 1% of blue-chip companies listed on the DAX stock exchange would be considered ‘sustainable’ if the EC’s draft… had been applied in its current form. The percentage rose to 2% for the French CAC 40 and the Euro Stoxx 50 indices.” This led to warnings that the taxonomy could end-up generating “an unsustainable ‘green bubble’ detached from fundamental data.”

There is also opposition within the European Parliament from a group of MEPs from eastern EU countries calling for the taxonomy “to secure a transition fuel status for the most efficient gas technologies.”

Increasing industry engagement and opposition from a significant number of EU member states mean that there are quite a few key sticking-points in the taxonomy that need to be addressed if it is to receive the required support.

Unresolved issues

Evidently the fight for natural gas, which started in December, is by no means over. And this has now been extended to include nuclear, biomass and forestry. There are still many challenges to be overcome before a final compromise is reached.

And with EIB ceasing support to gas projects, it may push project developers to go for loans from Chinese banks. Chinese investment in central and eastern Europe is gaining momentum. Teaming up with China on big infrastructure projects allows such countries to obtain funding for projects that are usually considered ineligible for funding by the EU or European banks owing to potential environmental or financial unsustainability.

Czech MEP Ondrej Knotek told a webinar that the taxonomy should not create barriers, but instead incentivise businessed with their energy transition projects. Specifically:

- Taxonomy should be protected from ideology;

- It must be compatible with reality;

- There should be synergy between public and private finance and in this respect the role of EIB is vital – the bank must rethink its role; and

- In some countries transition investment includes natural gas and this must be recognised.

He said that similar arguments apply to nuclear energy. The taxonomy must be updated accordingly. In addition, the EIB should eventually update its criteria to align them with the updated taxonomy.

What is clear is that countries that now rely on coal should have the required time and support for transition – they should not ‘be left behind’, to recycle an EC phrase referring to the Green Deal and its just transition.

Clearly there is confusion about what is the energy transition, in the context of the taxonomy. The strong pushback by the ten EU member states, the natural gas, bioenergy and forestry industries has raised concerns of a ‘dilution in the taxonomy’s criteria’.

But that may be the wrong way to look at it, if the draft criteria do not reflect a wider buy-in, other than the views of experts and climate campaigners. The pushback by the ten member states and industry needs to be addressed. Only then the taxonomy will become more balanced and receive the required buy-in.

Even the European Central Bank appears to have decided to adopt a less aggressive approach to tackling climate change and rely mostly on improved financial modelling and disclosure rather than take the lead on tackling environmental issues, as many climate campaigners are asking. The bank prefers to leave that to governments.

This is not just a science exercise, it is also highly politically and economically sensitive. As Total CEO Patrick Pouyanne, said: “There is a lack of debate among politicians and environmentalists over how much it will cost consumers.”

However, Europe still needs to achieve its 2030 and 2050 emission targets and it is a long way from doing that, requiring drastic changes – more energy efficiency, more renewable generation, electrification, a shift to electric vehicles and phase-out of coal.

The European commissioner for financial stability and the capital markets union Mairead McGuinness told the European Parliament that “it would be useful to take a step back and to look at what the taxonomy is, and what it is not,” adding that “the EC will consider recalibrating the technical screening criteria where serious concerns are raised, but we don’t want to break the link with science or the alignment with Green Deal targets.” It remains to be seen what the outcome will be, but without compromise it will carry on facing challenges.