Czech Republic Adopts Nord Stream 2 [NGW Magazine]

No one ever accused Czech foreign policy of being overly assertive. Like its favourite literary creation, the Good Soldier Svejk – the ultimate survivor in a Europe torn apart by World War 1 – the small country has managed to avoid trouble by quietly navigating its way through the plans of competing world powers.

Prague’s journey through the controversy surrounding Nord Stream 2 (NS2) illustrates this expertise. As the giant Russian gas pipeline becomes a reality, the Czechs are increasingly comfortable in admitting that they want to play a role.

Despite the furious opposition of many central and eastern European (CEE) states that has been encouraged by the US, Russia began building the route below the Baltic Sea in September. Planned to be ready by the end of 2019, NS2 should eventually pump an extra 55bn m³/yr directly to Germany, running roughly parallel with NS1, and from where it will be distributed across the region.

Moscow and Berlin insist the project is purely commercial. Opponents, led by the Czech Republic’s neighbours Poland, say the project is geopolitical, and part of Russian efforts to further destabilise Ukraine by cutting its transit role for gas headed to the EU. Events in the Sea of Azov in late November did little to convince them otherwise.

Moscow says Ukraine is an unreliable partner, and that it wants to halt transit through the country by the end of next year in order to better serve EU markets. It also says that it is quicker and cheaper to export gas through NS2 as its production base moves further north into Yamal.

Poland and its cohorts complain NS2 will deepen CEE’s dependence on Russian gas, reducing energy security and raising the Kremlin’s political leverage across the region.

However, the Czechs were lukewarm about joining the protests from the start. Now, with the EU having all but admitted defeat in its efforts to block NS2, Prague has become increasingly open about which side it’s on. Eyeing a major role in transiting the gas NS2 will deliver, the country hopes to secure raised transit revenue, lower gas prices, and a hub role.

“For the ministry of industry and trade the NS2 project is a purely commercial activity,” spokesperson Milan Repka told NGW.

Those words back up Berlin and Moscow, as well as Repka’s boss. In October, Marta Novakova signalled Prague’s about-face as she made her country’s support for NS2 concrete.

“If the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline were not launched for any reason, the existing transport contracts would gradually expire across the Czech Republic," the minister stated, adding that "the failure of Nord Stream 2” would bring considerable risks for the Czech Republic.

(Not) Gazela 2

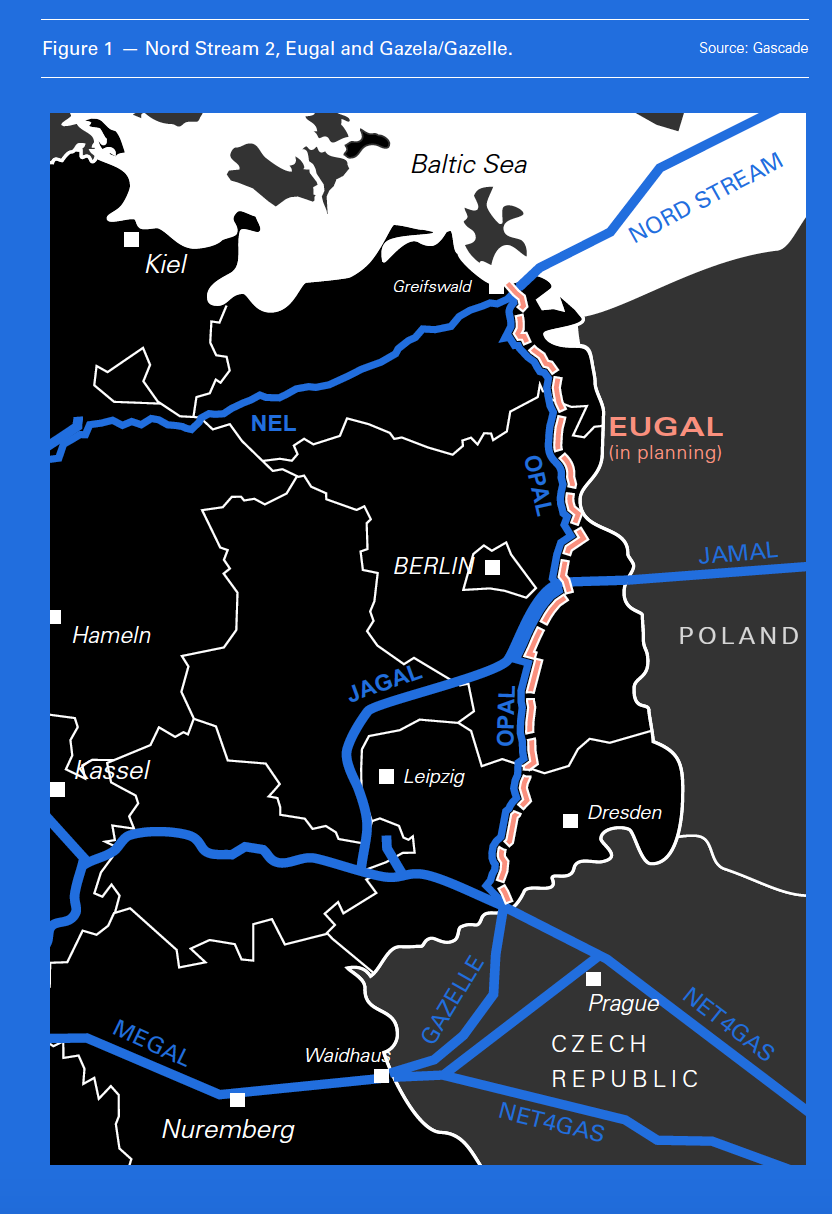

The Czech enthusiasm is no surprise. The country already plays a major role in distributing gas arriving via NSI, launched by Russia in 2012. On making land in Germany, the 55bn m³ route meets the Opal pipeline, and then heads out across European networks. To the south, Opal meets Gazela. Launched in 2013 by the Czechs, the 30bn m³ pipeline runs 169 km to link to Bavaria, as well as the mainline route through the Czech Republic running eastwards to Slovakia.

Transmission system operator (TSO) Net4Gas is now building a second line under the €740mn Capacity4Gas project. Although not officially called Gazela 2, the pipeline will shadow its forerunner down the western side of the country and will effectively double the volume of gas transiting the Czech Republic.

Net4Gas sold capacity of 40bn m³/yr from 2020 - 2039 at an auction that closed in March 2017. The TSO does not specify that the new pipeline is intended as a link for NS2 gas, but few are fooled. The capacity of the new route matches expected flows from the Russian project. It is due to be ready to launch in 2019.

It is reported that Gazprom Export booked up to 90% of the capacity at the auction. Analysts at Standard & Poor’s worry that this will deepen the Czech TSO’s reliance on Gazprom for revenue to 70%.

While refusing to comment on the identity of the buyers of the capacity on the new pipeline, Net4Gas spokesperson Zuzana Kucerova tells NGW that the company is now “legally obliged to implement the project resulting from the binding capacity auction.”

“This is a sign that NS2 is going to happen,” asserts Martin Jirusek at Masaryk University’s Center for Energy Studies. “Companies like Net4Gas wouldn’t be investing if they weren’t certain it will go forward.”

Gas is gas

Germany is the Czech Republic’s key economic and political partner. Russia supplies the vast bulk of its gas, oil and uranium. Poland – alongside Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia – is a partner in a Visegrad Four (V4) group in which all talk of unity and shared interests but rarely deliver.

The opposition to NS2 by the Russophobic Polish government, as well as others in CEE such as the Baltic States, remains elevated. Poland’s prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki told a Nato meeting earlier this year that the pipeline is “a weapon of hybrid warfare that Moscow wants to use to undermine European energy security and the solidarity of the European Union and Nato.”

But the Czechs are not supporting NS2 out of some pro-Russian foreign policy stance. Despite the rhetoric of the populist president Milos Zeman, official government policy in Prague baulks at the Kremlin’s renewed imperial ambitions in the region. Rather, the support for the pipeline stems from Czech Republic’s deeper connections to the west.

Energy market infrastructure linking to western Europe was built in the 1990s and now offers the Czechs access to the German exchange and Norwegian gas, in addition to the Russian flows that have long arrived via the mainline through Ukraine and Slovakia. Security of supply has been a non-issue since. However, plugging itself into western energy markets means the country has little choice but to adapt to Germany’s deepening co-operation with Russia.

For Prague, that puts the stress on the potential effects that on Czech energy security and domestic gas prices should the country refuse to play ball.

“Gradually expiring Net4Gas shipping contracts would certainly not be renewed at current pricing,” points out Repka. That, he warns, would raise the cost of running the transmission system and therefore increase gas prices for Czech customers.

NS2, on the other hand, would lead to significant additional volumes of transit, and have the opposite effect. “At the same time,” he continues, “the strategic role of the Czech Republic in international gas transit and the increased security of gas supply in the CEE region would be strengthened.”

Little wonder that the Czechs seek to evade geopolitical concerns expressed by Poland and its allies. “We don’t get this anti-Russia rhetoric, as the whole logic of the common EU market is that when Russian gas crosses EU border, it’s no longer Russian, nor Norwegian nor Algerian. It’s simply gas that is measured by its economic value,” Czech ambassador-at-large for energy security Vaclav Bartuska said last year.

Reality

However, it’s taken a while for the Czechs to get to that point. Prague’s pragmatic foreign policy demanded it hedge its bets at first. In early 2016 the then-prime minister even signed one of the gentler missives from CEE states calling on Brussels to watch the project closely. However, as German pressure and legal shortcomings have undermined the bloc’s challenge to NS2, the Czechs have climbed down from the fence.

When Gazprom and its German partners began laying the first pipes in the Gulf of Finland on September 5, confidence in Prague blossomed, allowing Novakova to announce the turnaround openly.

“The rhetoric has adjusted to reflect the reality on the ground that NS2 will be finalised,” says Jakub Groszkowski of Polish think tank OSW. “This is not the rhetoric they used three years ago.”

While Poland – which says it will ditch Russian gas entirely once its long-term contracts expire early next decade – looks set to drop plans for a new interconnector to the Czech Republic, “Gazela 2” is unlikely to damage relations inside the V4 significantly. In fact the Czech prime minister Andrej Babis and Polish peer Mateusz Morawiecki have been developing ties in recent months.

Poland would be hard pressed to justify any action against Czech Republic, given Warsaw’s ongoing confrontation with the EU over issues of national sovereignty. Many point out that the liberalised energy market means the government probably could not stop Net4Gas – which is owned by German and Canadian interests – from co-operating with NS2 anyway.

In addition, the Czechs are not the only V4 member to have changed their tune as NS2 takes on more solid form. Net4Gas will carry much of the gas it collects from NS2 south-east to Slovakia, where the Eustream TSO is busy expanding its own capacity. From its border, Slovakia will send the gas on towards the Baumgarten hub in Austria.

At risk of losing huge transit revenues from its originally 90bn m³/yr system should Russia manage to end its use of the Ukrainian route to western Europe, Slovakia was initially strongly opposed to NS2. That is still the official stance of a government that owns 51% of Eustream; but Bratislava is also forced to bite the bullet, and is casting around to pin down new roles to keep gas flowing through its network. Securing an eastwards diversion for NS2 flows has largely quashed Slovak complaints about the Russian mega-project.

“There’s a gentleman’s agreement that the Czechs won’t build a link directly to Austria and cut the Slovaks out of the transit,” suggests Jirusek. “Without that, Slovakia would be far more strongly opposed to NS2.”