Country Focus: Sri Lanka – a new market entrant? [LNG Condensed]

Sri Lanka is a lower-middle income country with a population of 21.7mn and average annual GDP growth of 5.3% between 2010 and 2019, according to the World Bank. GDP slowed to 2.3% last year and contraction is possible this year as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

It has no gas production of its own, but two discoveries were made in the Mannar basin in 2011 and subsequently relinquished. Bids for the block were received last year, but the licensing award process is proving slow. In the interim, plans are afoot to import LNG, which would reduce both the cost of energy in the country and greenhouse gas emissions. Sri Lanka is heavily dependent on coal and oil-fired generation to meet demand beyond the capacity of its hydro plants.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

The government has committed to carbon neutrality by 2050. The overall plan of the state electricity company, the Ceylon Electricity Board, is to increase total generating capacity from 4 GW to almost 7 GW by 2025 through the addition of more hydro capacity, wind, solar and thermal power plants.

Variability and unreliability

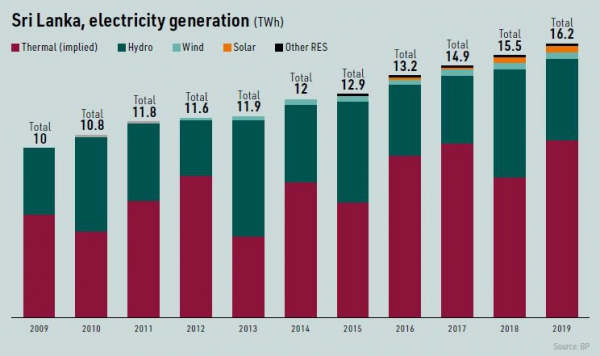

Sri Lankan demand for electricity is rising steadily, jumping 4.5% in 2019 to 16.2 TWh. Of this more than a quarter – 4.8 TWh was met by 1,719 MW of hydropower plant. However, water for irrigation and domestic use is prioritised over power generation and monsoon patterns have been highly variable over the last decade. Hydro provided 6.9 TWh of power in 2013 and 6.4 TWh in 2018, but only 4.2 TWh and 4.0 TWh in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

New capacity should increase overall output but variability will remain a factor. The country has no pumped hydro storage capacity although a potential 600 MW project is under consideration, which would be a major benefit in smoothing generation from wind and solar, which is starting to enter the generation mix. However, gas-fired plant would provide substantial system flexibility.

Sri Lanka also has to rely on the erratically-performing 900-MW Lakvijaya coal-fired power plant and oil-fired generation as a back-up, a combination which is both expensive and carbon heavy.

Currently, the cost of electricity generation is not covered by electricity prices, placing a significant burden on the country’s finances. The World Bank estimates that the government has been spending around $0.5bn/year on liquid fuel products for power generation.

Coal-fired power has proven unreliable. A first 300-MW unit, part financed by China’s Exim Bank, was completed in March 2011 and two additional 300-MW units were commissioned in 2014.

_f600x359_1606832768.JPG)

LNG projects

Plans to build the country’s first LNG regasification terminal saw a letter of intent signed in September 2017. The terminal will be 47.5% owned by India’s Petronet, 37.5% by Japan’s Sojitz Corp. and Mitsubishi, with the remaining 15% held by the Sri Lankan government through Sri Lanka Gas Terminal.

Petronet and its Japanese partners plan to invest $250-$300mn in the floating LNG project, which is expected to have capacity of about 2.6mn mt/yr. Petronet said in November that the project was pending government approvals and that no development work was expected before March next year.

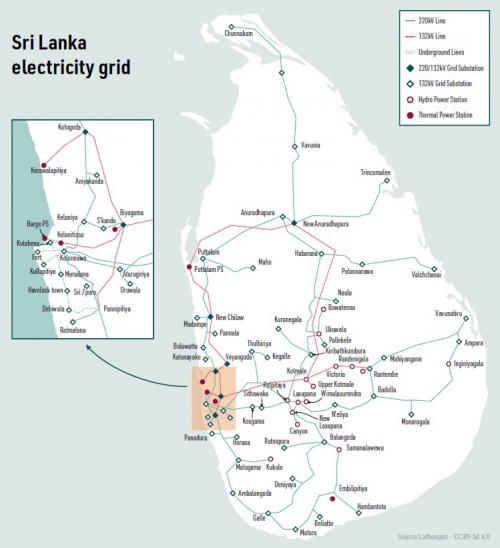

The terminal’s anchor customers will be two 500-MW gas-fired power plants to be built in Kelanitissa and Kerawalapitiya on the west coast of the country near the capital Colombo. One is a joint venture between India’s state-owned National Thermal Power Corporation and CEB. The second plant is being developed by Sojitz Corp. Mitsubishi and CEB.

Meanwhile, in late August, the Board of Investment (BOI) of Sri Lanka signed an agreement with Pearl Energy to develop an LNG hub at the Port of Hambantota on the south coast. Pearl plans to deploy a floating storage facility with the primary aim of trading LNG in the region. The total investment in the project is expected to be $97.2mn.

The floating storage unit will have an initial capacity of 1mn metric tons/year and Pearl will deploy small LNG carriers to redistribute LNG to south India and the Maldives, BOI added.

Pearl’s director Tania Siegertsz said that although the project will primarily target regional trade, the company expects Sri Lanka to switch to gas-based power generation and increase the efficiency of its national grid. The port could also start LNG bunkering services thereby making Hambantota and its industrial zone a ‘clean energy zone’ of the future, she said.

A 400-MW gas-fired power plant is also planned at Hambantota at a cost of $500mn. This is to be built by CMEC. Chinese state interests assumed control of the deep-sea Hambantota port in what was reported as a debt-for-equity swap in 2017. The plant is expected to be operated by CEB and CMEC.

Domestic gas still on the horizon

The government’s plan is for the import of LNG for an interim period before domestic gas production begins. However, domestic gas production remains some way off.

Sri Lanka held licensing rounds for three offshore oil and gas blocks, M1, M2 and C1, in 2019. In August last year, the government announced that it had received three bids for the M2 block in the Mannar basin off the west coast. Vajira Dissanayake, a government official in the petroleum ministry, said the block was expected to be awarded by November.

The M2 block covers an area of 3,500 km2 and has two gas discoveries, Dorado 91 H/1z and Barracuda 1G/1, and a number of undrilled prospects. The two discoveries were made by Cairn India in 2011, but the company gave up the licences in 2015, saying the finds were not commercially viable. Cairn made a mid-case estimate that the two discoveries held recoverable resources of 24bn m3 of gas and 5.88 million barrels of condensate.

In December last year, local press reported that the project committee of the Petroleum Resources Development Secretariat had completed the bid evaluation process and sent its report to the Petroleum Resources Development Ministry. The report should then have gone to the Cabinet-Appointed Negotiation Committee (CANC) prior to approval by the cabinet of ministers. However, CANC was not functioning at the time, owing to a change of government.

In August this year, the Sri Lanka People’s Party won 145 seats in parliamentary elections, which with allies gives it a two-thirds majority of the 225-seat house. The election result consolidated the power of the SLPP’s Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who was elected president in November 2019.

Last year, the government also entered into an agreement with France’s Total and Norway’s Equinor as a joint study partner to explore the hydrocarbon potential in two offshore oil and gas blocks. The two blocks, JS -5 and JS-6, are in the Lanka Basin in the eastern offshore region of Sri Lanka.

Low gas prices this year followed by the demand impact of the Covid-19 pandemic have caused international oil and gas companies to rein in their investment spending. Even if a licence award were made and the companies proved willing, the M2 block would probably take three to four years to bring into production assuming exploration work provides positive results.