Country focus: Coal phase out and gas hub ambitions fuel Greek LNG plans [Gas in Transition]

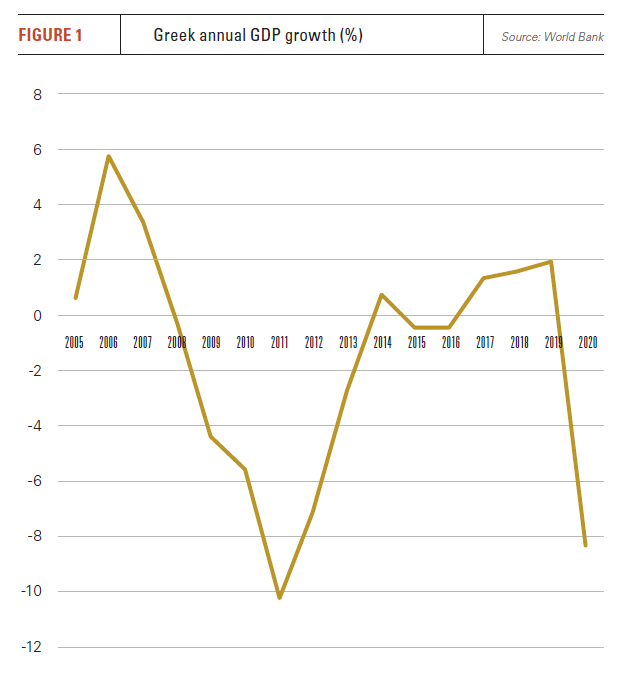

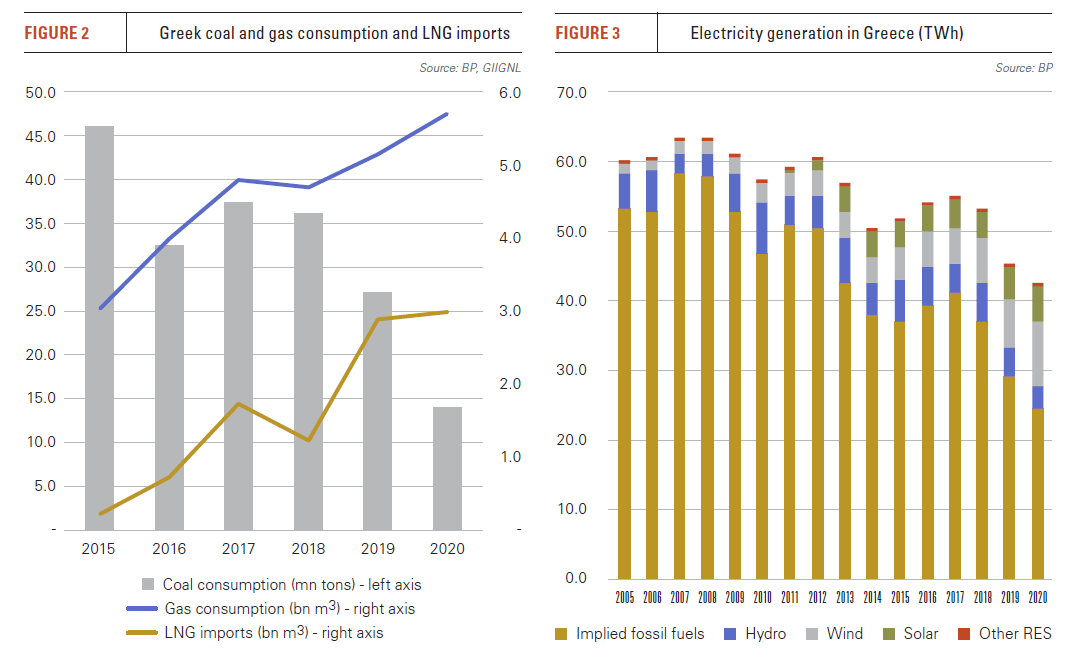

Having suffered a decade of economic hardship, the Greek economy returned to growth in 2017-2019 only to be hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The Greek economy contracted by 8.25% last year (Figure 1). However, gas consumption (Figure 2) has been on a gradual upward trend, reaching a record 5.7bn m3 in 2020, up from a recent low of just 2.8bn m3 in 2014.

Greece has minimal gas production of its own and sources imports by pipeline, primarily from Russia and Azerbaijan, and as LNG through its sole LNG terminal, Revithoussa, near the capital Athens.

Import capacity exceeds domestic requirements by some margin, but Greece is keen to build on its growing role as a regional gas hub and transit country. This capacity was significantly enhanced by the start-up of the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) last year. TAP takes gas from Greece to Italy and is an extension of the Azeri gas-carrying Trans-Anatolian Pipeline.

Completion of the Greece-Bulgaria interconnector, expected by the end of this year, and the possible construction of a new pipeline from Bulgaria to Serbia should also bolster Greece’s role as an entry point to southeast European gas markets.

Domestic demand

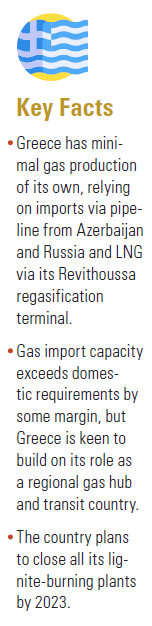

Domestic gas demand has been growing in tandem with renewable electricity generation alongside a decline in coal use. Coal provided 11% of primary energy supply in 2020 and about one-fifth of electricity generation. Coal – primarily domestically-mined lignite – has been a long-term mainstay of the Greek electricity system, but increased gas availability, lower import prices and higher carbon prices are contributing to greater gas burn for power generation.

Coal-to-gas switching is a fundamental part of the country’s emissions reductions strategy. In its 10-year National Plan for Energy and Climate (NPEC), submitted to the EU in December 2019, Athens committed to a complete phase out of coal use for power generation by 2028.

However, it has subsequently brought that target forward and aims to close all lignite burning plants by 2023, with the exception of the newbuild Ptolemaida 5. The state-owned Public Power Corp had planned to run the plant on lignite until 2028, but announced in April that it would be converted to gas with a capability to burn blended hydrogen, effectively bringing Greece’s coal age to an end three years ahead of schedule.

Renewables start to accelerate

Greece has a target, under its NPEC, of increasing renewable energy consumption from 17% in 2020 to 35% by 2028. Its focus so far has been on solar and onshore wind, but more ambitious plans are being formulated.

After a rapid period of expansion from 2010-2014, increases in solar capacity (Figure 3) stalled from 2013-2018, but with the decline in solar costs, and therefore less need for financial support from a cash-strapped government, the sector has begun to rebuild momentum. Capacity rose from 2.652 GW in 2018 to 3.247 GW in 2020, with the increase last year being the largest annual gain since 2013.

Onshore wind capacity has risen more steadily, but again the last two years have seen record annual increases, with capacity reaching 4.113 GW in 2020, following annual increments of 712 MW in 2019 and 524 MW last year.

Offshore wind has yet to reach Greece, but is likely to do so eventually. Steeply falling sea beds along most of Greece’s coastlines mean floating offshore wind farms are the most applicable technology, but floating offshore wind remains expensive.

There is also a lack of legal clarity in terms of licensing and spatial planning which needs to be resolved. In addition, the country’s best offshore wind resources lie in the Aegean Sea, where Athens may be reluctant to exercise its rights to 12 nautical miles of maritime territory from shore, owing to historic tensions with neighbouring Turkey.

Nonetheless, the contribution of renewable energy to the overall electricity mix has been rising. Solar and wind provided 14.2 TWh of electricity in 2020 out of total generation of 42.6 TWh, up from 7.5 TWh in 2014, when total generation was considerably higher at 50.5 TWh.

Renewables look set to increase their share of generation over the next decade, but not at a rate commensurate with the timescale for phasing out coal, which leaves open an opportunity for gas.

Hub expansion

Greece’s ambitions as a regional hub and transit state depend on the further construction of new pipelines to access growing gas demand in a region still heavily dependent on coal.

The Greece-Bulgaria interconnector will connect with the Greek national gas grid at Komotini and the Bulgarian grid in the area of Stara Zagora. The 182-km pipeline will have initial capacity of 3bn m3/yr, potentially rising to 5bn m3/yr if there is sufficient demand. There is also a possibility of connecting the pipeline to TAP, the operators of which are already mulling expansion, following the start-up of flows through the pipeline last year.

The Greece-Bulgaria interconnector will connect with the Greek national gas grid at Komotini and the Bulgarian grid in the area of Stara Zagora. The 182-km pipeline will have initial capacity of 3bn m3/yr, potentially rising to 5bn m3/yr if there is sufficient demand. There is also a possibility of connecting the pipeline to TAP, the operators of which are already mulling expansion, following the start-up of flows through the pipeline last year.

On May 17, TAP asked for capacity bids for the expansion. TAP is offering three scenarios for the 10bn m3/yr pipeline: a limited expansion to about 14.4bn m³ yr; a partial expansion to about 17.1bn m³/yr and a full expansion or doubling to 20bn m³/yr.

Meanwhile, the 171-km Nis-Dimitrovgrad pipeline is expected to start construction this year and be completed in 2023. This will link Bulgaria and Serbia, but also allow Serbia to access Greek LNG and Azeri gas coming through the EU’s Southern Corridor.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) has committed a total of €74.5mn ($88mn) in grants and loans to the project. The pipeline would serve as an alternative source to Russian gas coming into Serbia via Bulgaria from Russia’s Black Sea TurkStream pipeline.

Again, coal-to-gas switching plays an important part of these plans. Serbia is heavily dependent on coal for electricity generation, but wants to build a series of gas plants to reduce its dependence on the carbon heavy fuel.

LNG plans

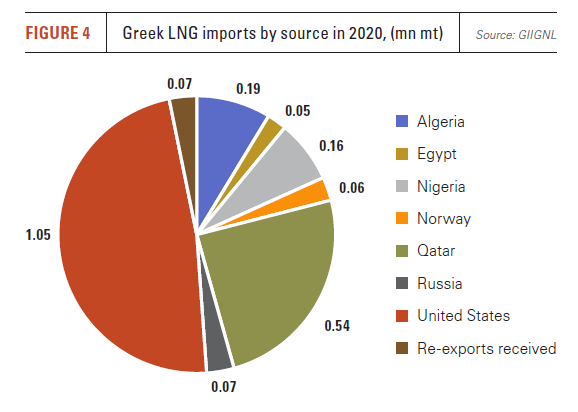

Current plans suggest significant competition between pipeline supplies and LNG (Figure 4) in terms of meeting regional gas demand.

Greece’s Revithoussa LNG terminal was completed in 2000 and expanded in 2018 to bring capacity up to 4.6mn mt/yr (6.3bn m3/yr), enough to meet more than the country’s entire gas import requirements. The plant is run by Greek gas grid operator DESFA and has three storage tanks with a total capacity of 225,000 m3. Imports in 2020 reached 2.2mn mt/yr, following 2.11mn mt in 2019, a significant jump from prior years.

There are also advanced plans for a second LNG facility, this time a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) to be located near Alexandroupolis. In June, the European Commission agreed a €166.7mn grant for the terminal, owing to the improvement it would make to energy security in southeast Europe.

The terminal is being developed by Gastrade, a consortium in which Greece's Copelouzos group is the largest shareholder. LNG shipowner GasLog, DEPA Commercial and Bulgarian transmission operator Bulgartransgaz each own 20% shares. Copelouzos has agreed on the sale of a further 20% to DESFA.

In April, Gastrade announced that it had signed agreements to co-operate with two companies from North Macedonia. National Energy Resources Skopje (NERS), which manages North Macedonia's gas distribution network, may take an equity stake in Gastrade. Meanwhile, North Macedonian electricity company AD Power Plants has expressed an interest in reserving some of the LNG terminal's regasification capacity on a long-term basis.

The FSRU will have regasification capacity of 5.5bn m3/year and storage capacity of 170,000 m3. It is expected to start operations in 2023, pending a final investment decision. It will be located about 17.6 km southwest of Alexandroupolis and connected to the national grid via a 28-km pipeline. According to Gastrade, the regasified LNG will be delivered to customers in Greece, Bulgaria, North Macedonia and the wider region, from Serbia and Romania to Hungary, Moldova and Ukraine.

In addition, Motor Oil subsidiary Dioriga Gas in June signed an advance reservation of capacity agreement underpinning a pipeline connection between a planned FSRU in Corinth and the national grid. The agreement enables DESFA to start on studies for a metering station with capacity of 12mn m³/day, the company said.

The aim is that in combination with the development of small-scale LNG infrastructure being built at Revithoussa, Dioriga's planned LNG barge reloading and truck loading facilities will allow greater LNG use in shipping, as well as bring gas to areas far from the existing reach of the country’s gas network.

This would build on plans to increase LNG bunkering in the country: in January last year, DEPA and the EIB signed an agreement to finance 50% of Greece’s first LNG bunkering vessel with capacity of 3,000 m3, which would be based in Piraeus.

Hydrogen ambitions

Greece is starting to develop more ambitious energy transition plans. A consortium of energy companies said on May 18 the Greek energy system could become carbon neutral with the development of an integrated green hydrogen project.

The White Dragon project is being developed by state-owned gas company DEPAin collaboration with Advent Technologies and a group of major Greek energy companies, including Hellenic Petroleum and gas pipeline operators, including the operating company of TAP. DEPA is involved in a number of hydrogen-focused projects in the country.

The ambitious project aims to develop renewable energy capacity in Western Macedonia to produce green hydrogen, which would be stored for use in Advent Technologies’ high-temperature fuel cells to generate electricity and heat. The combined budget for the project, if approved in its entirety by the European and Greek authorities, is €8.063bn.