Chinese gas deal still eludes Moscow [Gas in Transition]

The last time Russian president Vladimir Putin visited China he returned to Moscow with the promise of a “no limits” partnership from his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. But the latest meeting between the two leaders in Beijing in October revealed a hard edge to the united front, as Gazprom failed again to clinch a highly anticipated deal to build the follow-up to the Power of Siberia (PoS) pipeline.

China and Russia’s leaders took centre stage in October at a two-day forum in Beijing attended by 23 heads of state mostly from the Global South. The meeting between Xi and Putin on the sidelines of the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation was at least their fourth since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, and the second this year after Xi visited Moscow in March in a strong show of support for the Kremlin.

Limitless friendship?

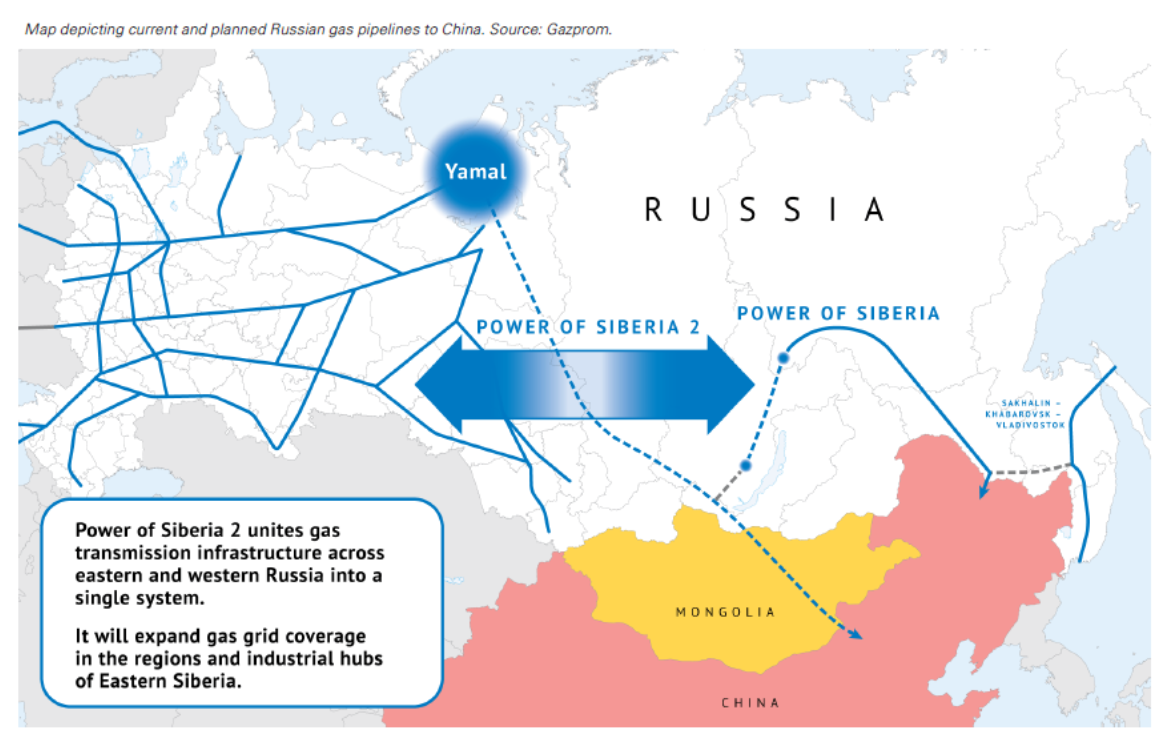

China-Russia energy cooperation had been in focus in the run-up to the high-profile summit. Russia has been aiming to redirect trade towards Asia after being shut out by Europe over its Ukraine war. One of Russia’s priorities in terms of joint infrastructure projects with China is building the PoS 2 pipeline, which is set to traverse Mongolia and enable Moscow to sell more gas to China.

For months Moscow has said talks with China on PoS 2 were “in the final stages”, but there has been little visible progress on key terms such as pricing and volume. Accompanying Putin to Beijing was Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller, and hopes were high of securing a contract to build the pipeline to export 50bn m³/year to China.

Gazprom is currently contracted to deliver 38bn m³/yr through the existing PoS 1 pipeline under a 30-year contract worth $400bn, and another 10bn m³/yr from a separate pipeline known as the Far Eastern Route. Finalising PoS 2 would double Gazprom’s contracted piped gas transmissions to China to nearly 100bn m³/yr compared with around 150bn m³/yr to Europe before the war.

While Gazprom did not leave Beijing empty-handed, China’s steady unwillingness to sign up for a second pipeline that would double Russian imports raises questions about the “no limits” friendship touted by Beijing and Moscow – especially after Kazakhstan capitalised on the lack of progress to sign its own supply agreement.

Beijing demurs

The proposed pipeline would be a gamechanger for Gazprom, which now pipes only 10-15% of the gas to Europe that it used to before the Ukraine conflict. The decimation of Gazprom’s European sales was unwittingly underlined by Miller, who said in an interview that the company’s pipeline gas supplies to China could soon overtake volumes sent to Europe.

The development of PoS 2 has major geopolitical ramifications and would reshape China’s energy landscape, but it has proven hard to close. China kept Gazprom waiting for more than a decade before the PoS pipeline was agreed and built, and appears to be dragging its feet again through long and painstaking negotiations.

China has no urgent need for the pipeline and Beijing knows Russia has limited export options for pipeline gas following the collapse in supplies to Europe, so it wants to secure a good price before signing a deal. China’s pragmatic leaders will also have observed Europe’s trouble with overreliance on Russian gas and taken in the lesson of depending heavily on one source.

At the same time there are good reasons why China may finally decide to contract for PoS 2. A new pipeline would reduce the need for seaborne LNG imports, which are more exposed to global tensions. For instance China imported 17.23mn tonnes of LNG from the Middle East last year that made up 27.1% of total imports, according to Chinese energy officials.

Most of this volume will have been shipped through the strategic chokepoint of the Malacca Strait that links Asia with the Middle East and Europe.

Most of this volume will have been shipped through the strategic chokepoint of the Malacca Strait that links Asia with the Middle East and Europe.

China also needs significantly more gas to decarbonise its power mix while mitigating the intermittency of renewable energy sources. Gas-fired power generation in China is expected to increase alongside renewable energy generation, from 300 TWh last year to 600 TWh in 2030 and 800 TWh in 2040, according to the International Gas Union’s annual Global Gas Report released on October 19.

“The additional gas-fired capacity acts as a backup and dispatchable energy source in the event of a shortage of renewable power generation, enabling China to call on a stable source of energy with quick ramp-up capability,” the report said.

Moscow’s inability to clinch a deal on PoS 2 came despite encouraging rhetoric from Putin and Xi at the Belt and Road forum. “Everyone approved of this project and all parties want to participate. The next step is its implementation. I think we will be moving fast,” Putin told Mongolia’s president. Xi meanwhile told Putin in their bilateral meeting that he hoped the pipeline would make “substantive progress” as soon as possible.

In the end Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told Russian state news agency Tass that “no documents on [PoS 2] will be signed this time”.

While no contract emerged Gazprom did strike a deal to export more gas than planned to China this year via the existing PoS pipeline, which is scheduled to ramp up to its full capacity of 38bn m³/yr by 2025. Gazprom announced it signed an addendum to the sales and purchase agreement for PoS supplies with CNPC for “an additional volume of Russian gas supplies to China until the end of 2023.”

Further details were not disclosed but Gazprom had originally planned to export 22bn m³ to China this year, up from 15.5bn m³ in 2022. Gazprom’s exports to China for the year to date are up by 46.6% year-on-year, according to the announcement.

Kazakhstan capitalises

Gazprom’s additional agreement with CNPC came shortly after China and Kazakhstan signed a new gas supply contract on Tuesday, one of 30 commercial documents signed between the countries with a total value of $16.54bn that included investment and trade agreements, technology transfers and new lines of credit. The deal will cover supplies from this year to 2026, according to Kazakhstan’s national gas company QazaqGaz.

China started receiving gas from Kazakhstan in 2017 under a five-year supply contract for 5bn m³/yr, which was then followed by a commitment to double supply to 10bn m³/yr in 2019. The original contract from 2017 was set to expire sometime this winter and it had been unclear if it would be renegotiated or renewed.

QazaqGaz CEO Sanzhar Zharkeshov has held a number of negotiations this year with the management of PetroChina International and its parent CNPC, and the Trans-Asia Gas Pipeline Company regarding the terms of a new export contract with China, according to Kazakh media. The Central Asian country presently ranks 15th in the world in terms of gas reserves, according to Zharkeshov.

CNPC also signed a separate cooperation agreement with Kazakhstan’s energy minister to extend “contract 76” of the Aktobe oil and gas production project to beyond 2025. The project in Kazakhstan’s Aktobe region is operated by the Chinese major, which agreed to develop it in 1997. The project has produced nearly 150mn mt of oil and more than 80bn m³ of gas, according to CNPC.

Central Asian imports

China presently imports gas from Kazakhstan through the Central Asia-China Pipeline, a multinational project comprising three cross-border gas pipelines that begin in Turkmenistan and transit Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan before entering China’s far western region of Xinjiang.

The first two pipelines are known as lines A and B, and each have a capacity of 15bn m³/yr while Line C can transport 25bn m³/yr, making for a combined capacity of 55bn m³/yr. Beijing signalled in May that it wanted to move forward with a fourth pipeline called Line D with capacity of 30bn m³/yr, which could complicate the picture for PoS 2.

The first two pipelines are known as lines A and B, and each have a capacity of 15bn m³/yr while Line C can transport 25bn m³/yr, making for a combined capacity of 55bn m³/yr. Beijing signalled in May that it wanted to move forward with a fourth pipeline called Line D with capacity of 30bn m³/yr, which could complicate the picture for PoS 2.

The Central Asian states – principally Turkmenistan – make up the lion’s share of China’s piped gas imports, which are also sourced from Russia and Myanmar. The Chinese General Administration of Customs stopped publishing detailed pipeline gas import data last year, but customs data from 2020 and 2021 showed that pipeline gas imports from Kazakhstan were in the middle of the cost range.

In 2020 for instance, Kazakh pipeline gas averaged $256.47/mt or $4.95/mn Btu compared with $9.08/mn Btu for pipeline gas from Myanmar, $4.14/mn Btu from Russia, and $5.60/mn Btu and $4.88/mn Btu from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan respectively, customs data showed.

In 2021 Kazakh pipeline gas averaged $4.70/mn Btu, which was cheaper than Turkmenistan’s $5.46/mn Btu and Uzbekistan’s $4.73/Mn Btu, but considerably more expensive than the $3.87/mn Btu cost for Russian gas. Myanmar shipments averaged $8.95/mn Btu.

Kazakhstan's peak gas production peaked at 39.2bn m³ in 2018 and has declined annually since then to 26.0bn m³ last year, according to the Statistical Review of World Energy.