China’s producers under pressure [NGW Magazine]

A decade ago China was producing 99% of the natural gas it consumed. Today policy-driven demand growth has put China on a trajectory of needing to import half its gas by 2030. Not surprisingly, the government is leaning on producers to raise their game.

China’s gas demand growth is – in volume terms – unprecedented. Between 2015 and 2017 it grew from 195bn m3 to 241bn m3, a rise of almost a quarter, and provisional data for 2018 indicate a further rise to around 270bn m3, or another 12%. That 2015-18 increment of 75bn m3 would on its own be the world’s tenth-largest gas market, on a par with the UK.

Chinese gas producers have been unable to keep up. They are therefore coming under rising pressure to boost production from conventional and unconventional sources such as shale gas, coal-bed methane (CBM) and even coal-to-gas conversion facilities.

China is already the world’s sixth-largest gas producer. More than 70% of its 147bn m3 output in 2017 came from conventional production, mainly from the Sichuan, Ordos and Tarim basins. Production was up 6.3% on 2016 but this was after two years of weak growth.

The country’s Big Three national oil and gas companies – China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC)/PetroChina, Sinopec and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) – accounted for around 95% of the total, with CNPC/PetroChina alone producing 73% of marketable production.

Phenomenal import growth

The inevitable consequence is that China’s dependence on gas imports is growing rapidly. According to Li Yalan, the chairperson of Beijing Gas Group Company (and due to become president of the International Gas Union in 2021), import dependence has grown from 32% in 2015 to 39% in 2017.

The figure for 2018 is likely to be over 40% – and is set to continue growing under current forecasts. Output by 2030 is expected to reach 260bn m3, says Li, while the medium-case demand forecast from the development research centre of the state council is around 520bn m3 – twice as much, as imports in little over a decade from now. A decade ago, it produced 99% of its consumption.

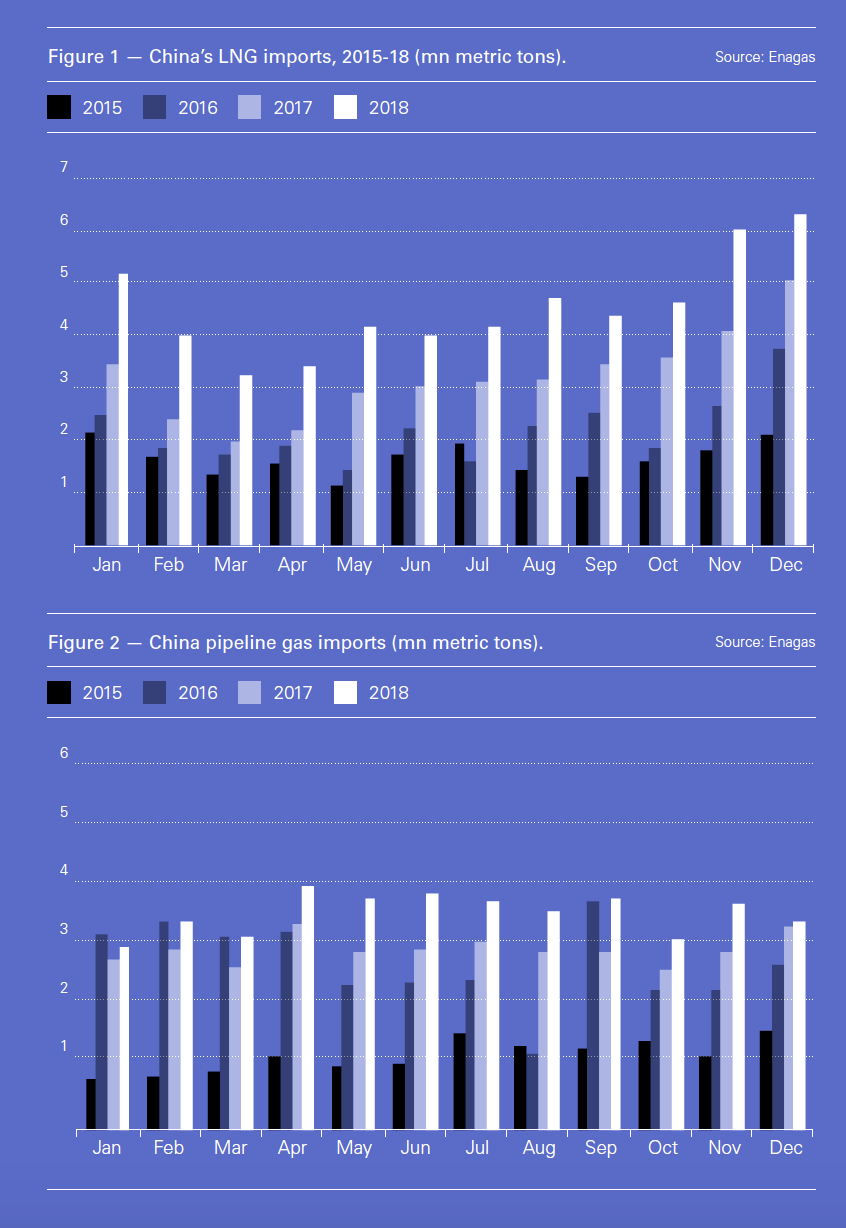

The growth of imports by pipeline and LNG has accelerated remarkably since 2015 as policies put in place under the president, Xi Jinping, to bring back blue skies to China’s cities and to meet climate pledges have taken hold.

In 2015 China imported 19.7mn mt (mn mt) of LNG. Following growth of 33% in 2016, 46% in 2017 and 41% in 2018, last year’s imports were 54.0mn mt. And this was despite a warmer than expected winter that has left the main LNG importers, the Big Three, facing short-term oversupply.

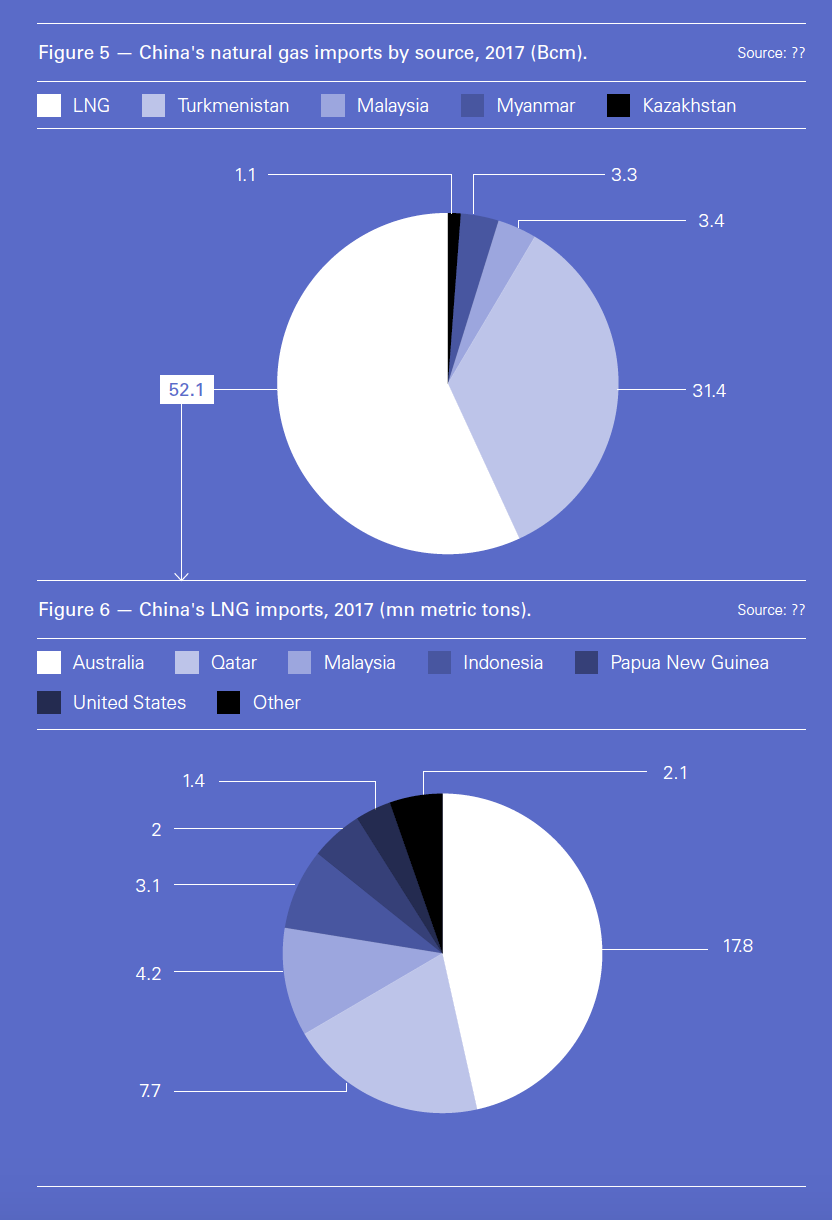

The chart below shows where all this LNG came from, and helps to explain why China is not overly concerned about having had to impose a 10% tariff on US LNG imports as part of the ongoing trade war initiated by US president Donald Trump. In 2017, the biggest sources of LNG imports were Australia, Qatar and Malaysia, with the US contribution a mere 1.4mn mt.

According to one senior Chinese source, the feeling is that LNG flows will adapt to minimise the impact of the US-China trade spat; a tangible benefit of the growing flexibility of global LNG trade. Indeed, agreeing to grow LNG imports from the US may be one of China’s strongest cards in the game of “call my bluff” still being played out.

Pipeline imports from central Asia and Myanmar have received less attention than LNG but they too have been soaring. In 2015 China imported 12.5mn mt of pipeline gas (17.0bn m3). Following growth of 124% in 2016, 9% in 2017 and 20% in 2018, last year’s imports were 36.6mn mt (49.8bn m3).

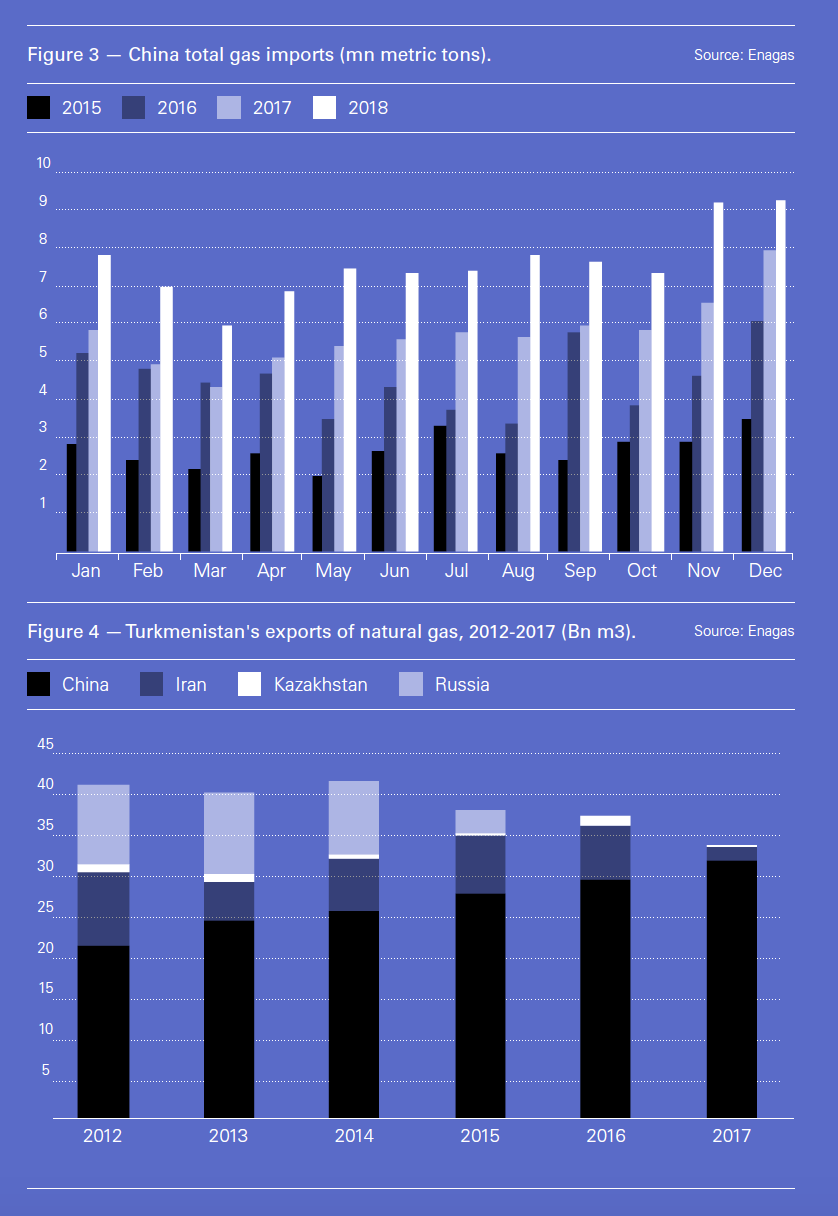

By far the largest supplier of pipeline gas is Turkmenistan, as the chart below shows. In 2017 it supplied 31.7mn mt, up from 29.4mn mt in 2016 and 21.3mn mt in 2012. Turkmen gas flows to China through the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline (CACGP). It is three-string (A, B & C) system that runs through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, who also use it to export their own gas to China. They hope eventually to raise their exports to 10bn m3/year each, but they now have output limitations and need gas themselves.

Meanwhile, exports from Turkmenistan to China have been growing in recent years, following the cessation of exports to Russia in 2016 and to Iran in 2017, as shown in the chart below. Turkmenistan has therefore become overwhelmingly dependent on China (94%) for its gas exports and constraints loom on further substantial growth, partly because of pipeline capacity and partly because a lot more investment is needed upstream. What new production there is has been largely funded and carried out with Chinese help.

Moreover, the future of the proposed Line D of the CACGP – which would take a different route through Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan – is in question following the indefinite suspension of work in Uzbekistan in 2017.

So, what happens next?

Two major questions now hang over China’s gas future and the impact of developments there on global gas markets. Will gas demand continue to grow at the kind of rates we have seen since 2015? And, if so, how will these needs be met?

The signs are that the demand surge is far from over. Even at the height of the severe gas shortages that gripped China in the winter of 2017/18 – because of the determined switch from coal to gas in heating and to a lesser degree in electricity generation – the government issued a clean winter heating scheme for northern China covering the period to 2021.

Led by the state’s planning division, the national development and reform commission (NDRC), the scheme focuses on the so-called “2+26” cities – Beijing, Tianjin and the cities surrounding them. The aim is to eliminate all coal-fired heating in urban areas by 2021 and achieve a “clean heating rate” of 70% in northern China by then.

It turns out that Chinese people like the return to blue skies. The coal-to-gas push has already achieved impressive results.

“If you come to Beijing often, you will see that these days the sky is clear, the air quality is good, kindergarten children no longer have to stay in the classroom and are able to go out for sports,” says Yanyan Zhu, general manager of the trading department at Cnooc, one of China’s LNG importers.

“The blue sky is something the whole nation wants and will never give back. So, in my opinion, the coal-to-gas policy will continue in the long run, which means gas consumption will grow.”

From a broader perspective, China’s 13th five-year plan for gas development, which was published by the NDRC in 2016, specifies that the share of gas in the primary energy mix should rise to between 8.3% and 10% by 2020, from around 7% now.

The authorities would like to see the top end of this range achieved; that is the figure that appears in the 13th Five-Year Plan for Energy Development and also in China’s climate pledge under the Paris Agreement – its nationally determined contribution (NDC). Looking further ahead, there is a target to increase the share of gas in the primary energy mix to 15% by 2030.

China is also working to expand its fleet of gas-fired power stations, with a total of 110 GW of capacity targeted for 2020, up from 68 GW in 2016, to reduce its heavy dependence on coal-fired power.

The five-year gas plan projects a total requirement of 360bn m3, of which 207bn m3 would be produced indigenously, mainly by China’s Big Three. Of this total, 167bn m3 would come from conventional gas production, 30bn m3 from shale gas – a target that looks unlikely to be met – and 10bn m3 as coal-bed methane (CBM). The remaining 153bn m3 would be imported by pipeline and as LNG, up from 123bn m3 in 2018. All these targets are a big ask.

There is a perception, say Yanyan, that pipeline gas ought to be cheaper than LNG and that domestic production ought to be cheaper than pipeline gas. Nevertheless, it seems likely that the call on LNG will continue to grow strongly.

Pipeline imports will grow when the 38bn m3/year Power of Siberia pipeline starts flowing Russian gas via the “eastern route” towards the end of this year. Work is already advanced at the helium-rich eastern Siberian gas fields and processing plant and an inauguration ceremony has been set for December 20 and there is determination, especially on the part of Gazprom, that it will go ahead as planned. But flows will take years to ramp up, partly because the necessary pipelines that will distribute gas within China are still under construction.

There has been a revival in interest in pursuing a second pipeline from Russia via the “western route”, but start-up is probably a decade or more away. That has always been more of a Russian than Chinese initiative anyway, as it would allow Gazprom to arbitrage between Asian and European markets, the gas coming from Western Siberian gas fields.

As for domestic gas output, conventional production is expected to continue growing but not at the kind of rates needed to make much of an impact on the demand-supply gap. Meanwhile, unconventional production is missing targets.

China began exploring for shale gas in 2010, with high expectations following the success of the shale gas revolution in the United States. In 2012 the government set a target of 100bn m3/year of production by 2020. It proved to be unrealistic and was subsequently lowered to 30bn m3. In fact, shale gas production reached just 9bn m3 in 2017 and is not expected to exceed 17bn m3 in 2020.

Under pressure from the government to make shale gas development a success, the main producers have been pouring resources into addressing the constraints. They are making progress but it will be years before these efforts make any meaningful impact. China may have world’s largest resources of shale gas but the challenges, below ground and above ground, are immense.

So, for the foreseeable future, much of the heavy lifting when it comes to satisfying China’s gas needs will need to come from LNG. China’s importers have already begun signing up long-term contracts after a period of appearing to be over-contracted. Expect more in 2019.