Chasing China’s power dragon [Gas in Transition]

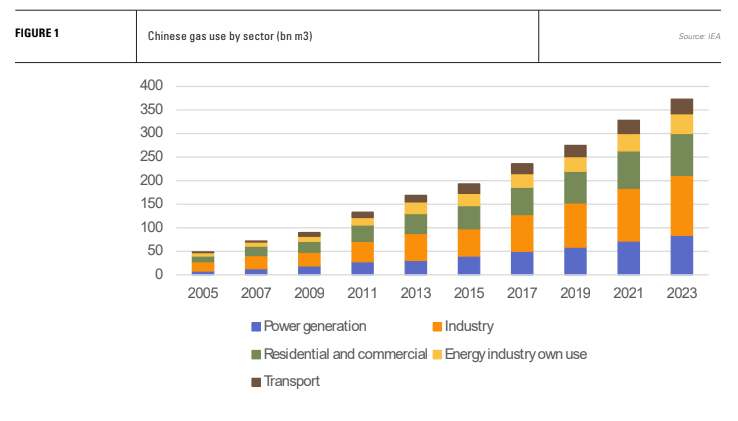

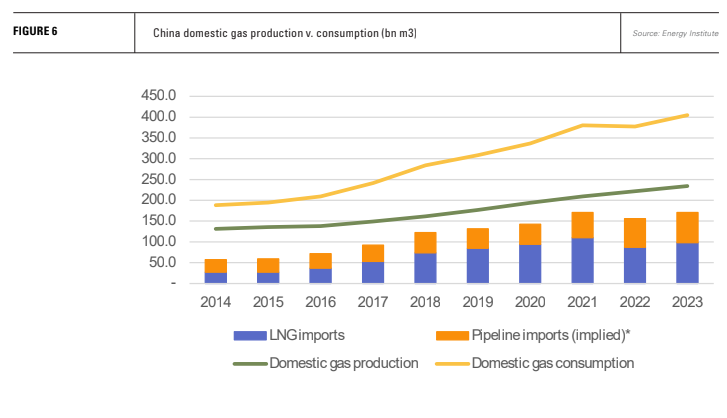

According to National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) data, Chinese natural gas consumption rose 7.6% in 2023 to 394.53bn m3. CNPC’s Economics and Technology Research Institute (ETRI) forecasts that it will rise by a further 6.1% this year to 415.7bn m3.

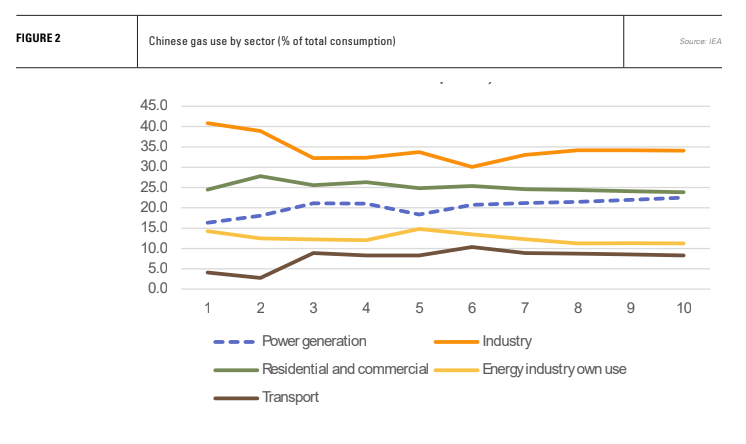

ETRI says gas for power generation will again be the fastest growing sector, increasing by 7.5%. This confirms the trend of the last few years, showing that the composition of China’s gas consumption is changing as the power sector emerges as a more important element of overall demand.

As a share of total gas consumption, gas demand for power generation rose to a record 22.5% in 2023, having recorded a steady upward trend since 2013, in contrast to stable or slightly falling shares for other major end-use markets. There has also been a steady increase in the construction of new oil and gas fired generation plants, almost all of which are gas-fired. New plant additions in 2023 totalled 12 GW, up from additions of 10.5 GW in 2022, 10.0 GW in 2021 and 8.4 GW in 2020.

Moreover, electricity generation from gas was relatively resilient in 2022, when international gas prices were at their peak. Gas-fired generation in China dropped from 287.1 TWh in 2021 to 275.6 TWh in 2022, but jumped back last year to a record 297.8 TWh.

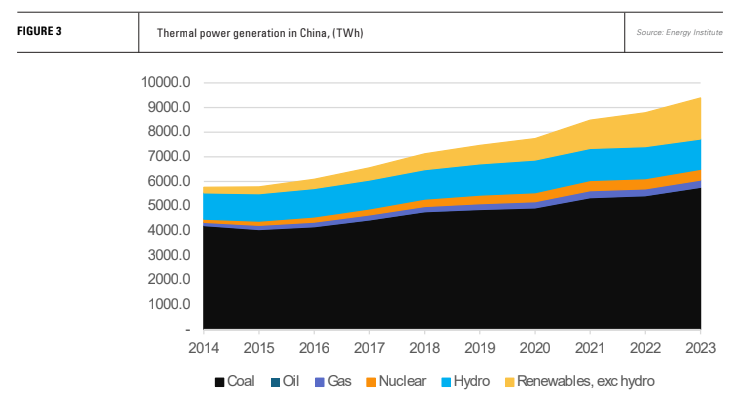

What is most notable, however, about Chinese gas use, is that it accounts for only 3.2% of power generation.

Non-fossil fuel growth too slow for demand

Soaring temperatures in China at the start of this summer will likely demand record levels of seasonal power output, as they did last summer, resulting in increased generation from the country’s expanding fleet of gas-fired generators. Some forecasters say this summer could prove the warmest in 2,000 years.

Heat has an outsized impact on China’s electricity sector. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), China’s stock of air conditioners rose from 531mn in 2015 to 862mn last year. The country accounted for more than a third of global air conditioner installations during the period.

Higher temperatures see air cooling demand rocket in the country’s urban areas during the summer, putting huge strain on the electricity system. China’s urban headcount numbers almost 900mn people, more than two and half times the US’s total population.

China is, of course, the world leader in solar deployment, with almost 610 GW in operation at the end of 2023, a huge 55% jump on 2022. This generated 584.2 TWh of electricity last year. However, solar’s daily curve sees generation peak around midday, while temperatures continue to warm into the afternoon, extending cooling demand well into the evening, creating a major headache for the country’s transmission system operators and creating a substantial market for daily energy shifting via storage.

Tackling coal

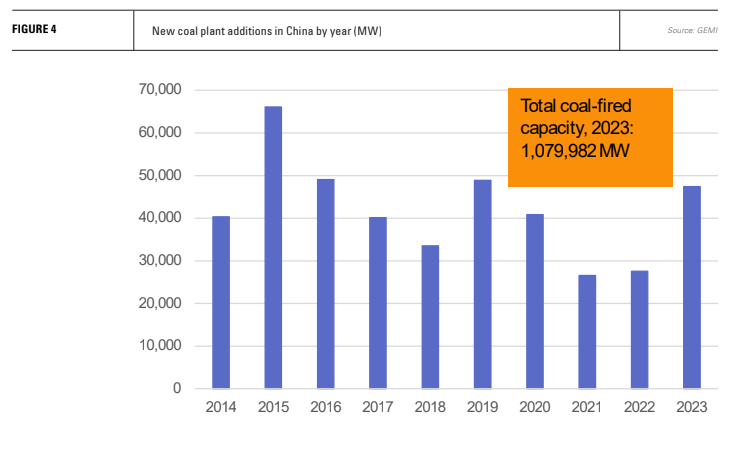

China can claim many records in terms of energy transition progress, but the fact remains that last year carbon emissions from the country’s coal-fired generation hit a record 5.56bn tonnes, up nearly 6% on 2022. Moreover, the country is still building new coal-fired power plants. 47.4 GW of coal plants came into operation last year, up from 27.6 GW in 2022.

The country has ambitious renewable energy targets and the capacity to deliver them. If China continues to add renewable energy capacity at the rate of 2023, it would be on track to triple its capacity by 2030, which would be a remarkable achievement. This will eat into coal-fired generation, but not as soon as might be imagined.

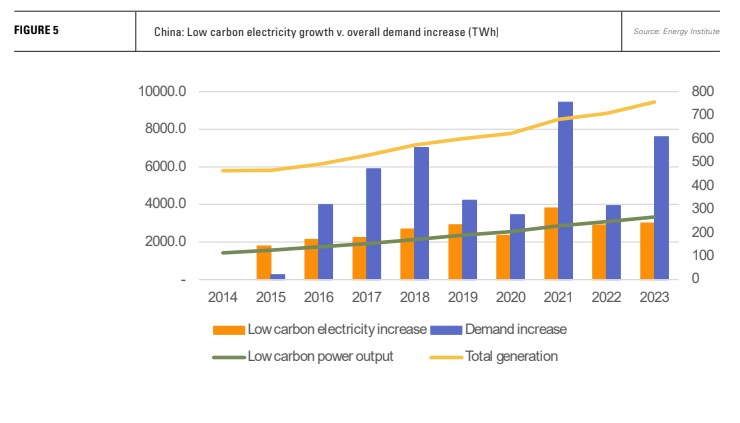

According to the IEA, Chinese electricity demand rose by 6.4% in 2023. Energy Institute data put the increase at 6.9%, which in output terms is 608 TWh.

Despite record deployment last year of wind and solar, electricity demand grew twice as much as the increase in renewable energy output, which was 295.6 TWh. The IEA estimates that the rate of power demand growth will fall to 5.1% this year – a forecast which may well be upset by cooling demand – and to 4.9% in 2025 and 4.7% in 2026.

As a result, even as renewable energy is deployed on an unprecedented scale, China has yet to reach the inflection point at which low carbon energy additions, in terms of output, exceed new demand growth. The government may not stop new coal-fired plant construction until then, and, even at this stage, it will still have a massive coal fleet providing the bulk of the nation’s power.

Emissions reductions via coal-to-gas switching

More so in China than in any other country, ‘all of the above’ solutions are required to address its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Given the massive preponderance of coal-fired generation and the relatively small use of gas for power generation, coal-to-gas switching represents a huge opportunity.

As has been well documented in the US, coal-to-gas switching has had an equal if not larger impact on GHG emissions reductions than the growth of low carbon energy generation. Between 2005 and 2022, US GHG emissions fell from 2,411mn t of CO2 to 1,507mn t. In this period, coal’s contribution to total electricity generation dropped from 50% to 19% and non-hydro renewable energy (wind and solar) increased from 2% to 17%. Gas-fired generation rose from 19% to 39%.

In a report published in January, the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) predicted that even in a case in which US carbon emissions fall by 95%, gas-fired generation capacity would rise by 130 GW. The US system would still need gas-fired power during times of critical demand for grid resilience and reliability, according to NREL.

Likewise, in China, CNPC sees a large increase in the country’s use of natural gas to mitigate GHG emissions as coal consumption falls. ETRI forecast at the end of last year that China’s gas demand would peak in 2040 at 605.9bn m3, at which point the share of non-fossil fuel would be somewhere in the region of 40-45% of the country’s primary energy mix. CNOOC in May put the country’s peak use of gas also at 2040, but with a higher figure of 700bn m3.

ETRI’s forecast was lower than in previous years and a low-case scenario posited 558.5bn m3 in 2040. However, the institute noted that gas for power generation would account for 70% of total demand growth. It forecast that increases in non-fossil energy supply would meet 80% of energy demand growth up until 2030, only after which would non-fossil fuels gradually begin to replace fossil fuel energy.

Imports key to expanding gas use

Unlike the US, China’s gas consumption outstrips its domestic supply, so the ability to import gas is fundamental to building gas-fired power generation to replace coal. Despite the promise of its own shale gas revolution, Chinese domestic gas production increased by only 102.9bn m3 between 2013 and 2023, while domestic consumption rose by 216.4bn m3.

Beijing will pursue all elements of providing gas security - i.e. increasing domestic production and attempting to ensure diversification of supply. Pipeline options remain relatively limited and provide point-to-point deliveries dependent usually on a single supplier. China’s Central Asian gas pipeline system enables it to tap into multiple points of Central Asian gas production, but is largely dependent on Turkmenistan. Imports from Myanmar look increasingly poor, amounting to only 3.7bn m3 last year.

Pipeline supplies from Russia will doubtless increase, but despite Moscow’s desire to find new markets for its gas, agreement on a second Power of Siberia pipeline with Beijing remains elusive. Moreover, despite the price highs of 2022, the prospect of large supply increases on the LNG market from the US, Qatar and other suppliers, alongside a peak in European demand, makes the LNG market increasingly attractive both in price terms and diversity of supply over the next decade at least. The most important demand centres for gas in China are also in the southeast, far from both Siberia and Central Asia.

It is therefore unsurprising that forecasts for LNG demand growth have China at their epicentre. Trade in LNG will increasingly become Asia focussed, with China as the anchor customer based on its need to achieve coal-to-gas switching on a large-scale as a key pillar of its climate change strategy.

With Mexican, Canadian and US LNG production set for major expansion, it seems likely that North America will fuel Asia’s energy transition with gas, just as China exerts all its might to sell its energy transition products back into North American markets. This implies further change in the Sino-US trade relationship, one which promises interesting times.