Can Germany manage without natural gas? [Gas in Transition]

In Germany there sometimes is a lot of optimism about the potential of renewable energy and scepticism about natural gas and oil. As a telling example, recently a group of politicians from Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU party published a position paper – more properly called a manifesto – proclaiming that Germany can become “the world’s first industrialised country running on 100% renewable energy.” They envisage reaching this goal as early as 2030.

What is more, according to the group, which calls itself KlimaUnion, ending the use of natural gas and oil completely by 2030 will make transport, heating and power consumptioncheaper than it is now, in part because it will save Germany €63bn ($74bn)/year that it now spends on the import of fossil fuels. “Better to spend 63 billion on the sun and on dikes than on Putin or sheikhs,” they write, describing the change to 100% clean energy as a “money savings festival.”

The KlimaUnion’s manifesto, which may be seen as an effort by CDU party members to make the party more attractive to climate-conscious voters in the upcoming federal elections in September, argues that all the required technologies to make a quick transition to 100% renewable energy are already available and only need to be implemented. Heating of houses can be done with heat pumps. Transport can be made all-electric. Batteries, hydrogen and other technologies will take care of storage needs.

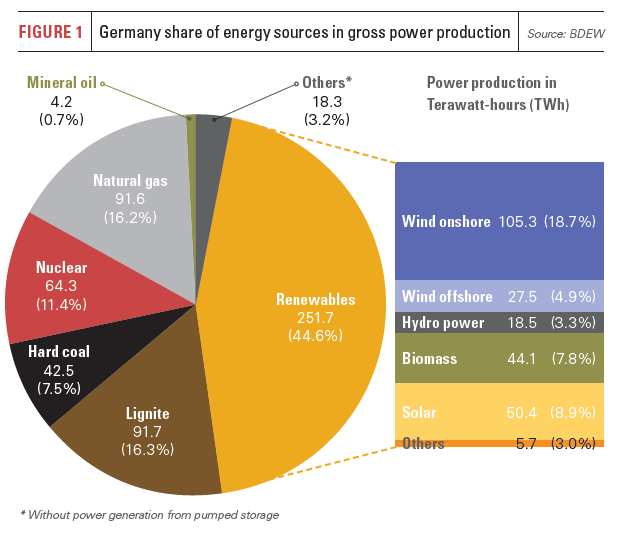

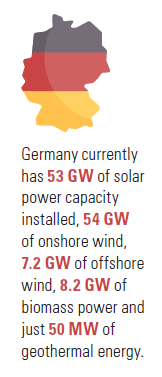

An added advantage of a quick transition to renewables: Germany will become independent from fossil imports, “no matter whether they come from the Middle East, Russia or North America”. Considerable efforts will be needed, the authors concede: every year Germany will need to build 8.5 GW of solar power capacity, 3.3 GW offshore wind, 5 GW onshore wind, 4 GW of bio-energy installations and 1 GW of geothermal capacity. Currently, Germany has 53 GW of solar power installed, 54 GW of onshore wind, 7.2 GW of offshore wind, 8.2 GW of biomass power plants, and just 50 MW of geothermal capacity.

Unrealistic

The KlimaUnion’s manifesto may appeal to German voters, but to outside observers it seems rather optimistic. Only some very rough calculations are given to support the idea that a 100% renewable energy system can work, or that it is cheaper than the current system. There is no discussion of space limitations or impacts on the landscape or of the need for imports of electricity from neighbouring countries and of hydrogen from faraway countries. The manifesto also contains some highly optimistic assumptions on energy savings.

Timm Kehler, chairman of Zukunft Gas, Germany’s leading gas advocacy group, says the propositions of KlimaUnion, are “unrealistic”. In an emailed response, Kehler notes, among other things, that “there are no indications that battery and power storage technologies will develop as rapidly as KlimaUnion assumes. There are also no indications that the price of batteries will drop. Lithium prices have actually increased significantly. Also, the assumption that all oil and gas heating can be replaced by heating pumps by 2030 is facing serious technological challenges. The existing building infrastructure in Germany is not compatible with a full rollout of heating pumps.”

While heat pumps “might be the first choice for new buildings, their deployment in existing buildings ranges from hard to impossible,” says Kehler. “In 2020, only 160,000 new heat pumps have been installed – compared to a total of 40mn dwellings in Germany.”

Furthermore, writes Kehler, “we lack the labour force for such a massive roll-out. We can already witness today a lack of qualified professionals. Our own studies suggest that a majority of buildings will continue to be heated by gas boilers in 2050 – but then fired by a climate neutral mix of hydrogen and bio-methane instead of natural gas.”

Blackouts

Kehler also notes that a successful rollout of renewable power will require the building of extensive new north-south transmission grids as well as a massive ramp-up of storage capacities and peak load capacities to cover seasonal shortages and shorter dark and windless periods. This, he points out, might be “technically possible”, but very costly.

“To make the energy transition affordable,” says Kehler, “Germany will need to continue to rely on efficient and fast back-up options such as gas-fired power plants, supplied by large underground storage capacities.”

Why gas-fired power plants? “Because they are the least CO2 emitting, they are ready within 10-15 minutes and they can supply reactive power to balance the grid frequency. The real question for us is not only how to reach the goal that Germany’s power demand will be largely supplied by renewables, but also on how to avoid blackouts and high costs.”

Kehler believes that as a result of the coal phase-out in Germany over the next years, “which might be accelerated by the new government”, the country “will see a renaissance of gas-fired power generation and a growing demand for gas. In addition, the phase-out of nuclear next year will increase the pressure to reduce the carbon footprint of Germany’s electricity production. Even the ambitious renewables scenarios forecast an increase in gas demand for power generation in the next years.”

The “renaissance” of gas-fired power is in fact already happening, notes Kehler. “Currently over 20 gas-fired power plants with a capacity of around 8 GW are either in planning or under construction. Most will be operational by 2022.” And it won’t stop there. “We see an even higher need after 2022. By phasing out coal and nuclear power, Germany faces a 45 GW gap of power generation, according to a study by the Institute of Energy Economics at the University of Cologne (EWI).”

The “renaissance” of gas-fired power is in fact already happening, notes Kehler. “Currently over 20 gas-fired power plants with a capacity of around 8 GW are either in planning or under construction. Most will be operational by 2022.” And it won’t stop there. “We see an even higher need after 2022. By phasing out coal and nuclear power, Germany faces a 45 GW gap of power generation, according to a study by the Institute of Energy Economics at the University of Cologne (EWI).”

Kehler does not expect gas-fired power plants to be converted to hydrogen before 2030. However, in the decades thereafter “converted plants will definitely be the first option to stabilise the power networks and assist renewables when weather conditions require.”

Capacity market

Clean Energy Wire (CLEW), a website funded by the Mercator Foundation and the European Climate Foundation, recently raised the same question in an article entitled Shutting down nuclear and coal – can Germany maintain supply security on renewables alone?

This article focuses on 2045, the German target date for greenhouse gas neutrality. CLEW notes that Germany’s conventional power generation capacity is beginning to dwindle. In December 2022, the country will have over 23 GW less nuclear power capacity than ten years ago. By the end of 2022, some 13.9 GW of lignite and hard coal-fired power stations will be closed according the coal exit law.

CLEW quotes several experts from the gas industry who insist that natural gas is indispensable for the time being. The head of Germany’s influential energy industry association BDEW, Kerstin Andreae, says that in addition to existing gas power capacity, “for a secure energy supply, we also need new gas-fired power plants, as this is the only way to obtain the required controllable power.”

Stefan Kapferer, the CEO of German gas transmission grid operator 50Hertz, confirms that “there will be situations where we will need back-up from gas power plants.” He told CLEW that Germany will need some 40 GW of gas capacity in the medium to long term. Total peak load in Germany is around 80 GW, current gas capacity is some 30 GW.

The question is whether investors will be prepared to put their money into new gas plants. Existing plants have long lain idle, notes CLEW. Germany does not have a capacity market, so there is no direct financial incentive to invest in back-up plants. “Every investor thinks twice before investing in gas backup capacities in Germany,” says Kapferer.

Imports

Not everyone is convinced about the need for gas power in Germany. Andreas Jahn of the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP) told CLEW that the existing over-capacities in the German and European systems are more than enough to ensure supply security, if renewable energy investments are on track and wholesale and CO2 markets can provide the required price signals. In this case, additional gas capacity will not be necessary at the moment. “If at all, we should look at using the existing plants not at investing in new ones,” he said.

The German economy ministry said in March 2021 that “enough CHP plants were being switched from coal to gas – something that is incentivised by the government – and that these capacities in combination with the European integration of energy systems and new powerlines would ensure supply security.”

But although Jahn and the ministry do not believe that under-capacity in the power system is on the horizon, they do stress that there is one important condition to ensure a stable power supply in Germany: European power grid integration. “Germany, still a net exporter of power, will have to import electricity more frequently. As its European neighbours are also transitioning to more renewables-based power systems, the countries will have to work together to support each other’s supply security.”

And that’s not even considering the need for hydrogen imports. Just recently, in July, the head of the German National Hydrogen Council, Katherina Reiche, said that Germany would need significantly more hydrogen than the government is currently counting on if the country is to meet its climate targets.

The country’s hydrogen production is currently 57 TWh/year, according to a new report from think tanks Fraunhofer ISI, ISE and IEG, produced almost entirely with fossil fuels. By 2030, demand would be up to 80 TWh, rising to 100-300 TWh by 2040 and 400-800 TWh by 2050. To establish a hydrogen economy, Germany needs to build large domestic capacities of electrolysers, massively expand renewables and the hydrogen transport infrastructure, said Reiche, but even then imports will be the leading source of supply, particularly after 2040.

If the German money does not go to Putin and sheikhs, it may have to go to Scandinava, Ukraine and North Africa.

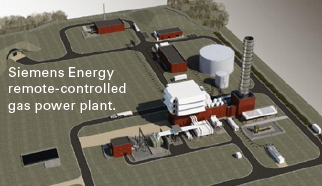

Siemens Energy to build unique remote-controlled gas power plant to support Bavarian grid

In what may be a world first, Siemens Energy will build a 300 MW remote-controlled grid-supporting gas fired power plant at a former military air base in Leipheim in Bavaria in the south of the country. The plant will be built for utility company LEAG at the request of transmission grid operator Amprion to ensure grid stability in an emergency and therefore ensure a reliable power supply in southern Germany.

“The Leipheim gas-fired power plant will be used exclusively to protect and ensure the reliability of the transmission grid,” Siemens announced in June. Siemens Energy will manage the operation and maintenance (O&M) of the plant for the first five years. It will be operated entirely by remote control from Siemens Energy’s Remote O&M Support Center (ROMSC) in Erlangen, Bavaria. According to the company, it will be one of the first power plants worldwide to be operated purely digitally from a remote location.

The special grid-related equipment will be installed on the grounds of the former military airbase in Leipheim, said the company. Siemens Energy’s scope of supply includes turnkey construction and the O&M agreement as well as an SGT5-4000F gas turbine, an SGen-2000P generator, and the SPPA-T3000 control system. The manufacturer will also provide a system for cooling the intake air and a system for injecting fully desalinated water into the gas turbine. These systems will ensure that the plant can generate up to 300 MW in as little as 30 minutes, even in hot weather.