BP’s Statistical Review 2016 - NGW Magazine

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 13

BP presented its 66th Statistical Review of World Energy 2016 (SRWE) in London on June 13, a review that is now in its 66th year.

Opening the presentation, BP deputy CEO Lamar McKay said that the key features of 2016 can be summed up as follows:

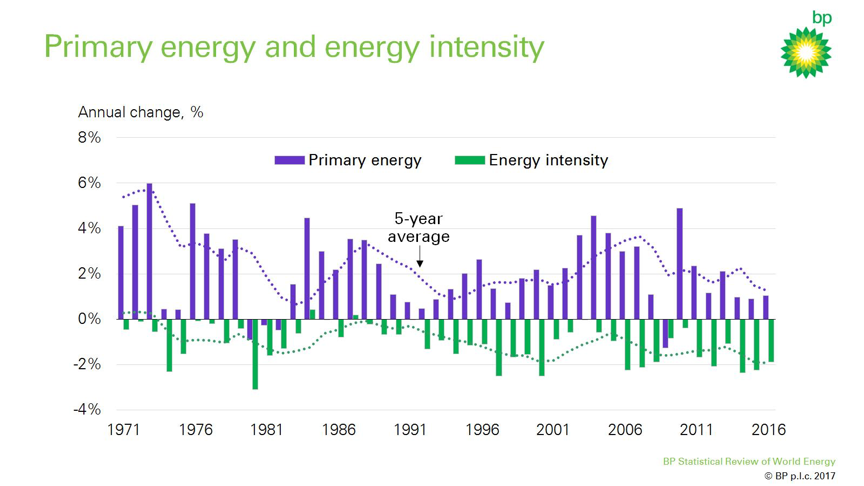

- Primary energy grew by just 1% in 2016, almost half the average rate seen over the previous 10 years – this is the third consecutive year in which energy consumption has grown by 1% or less.

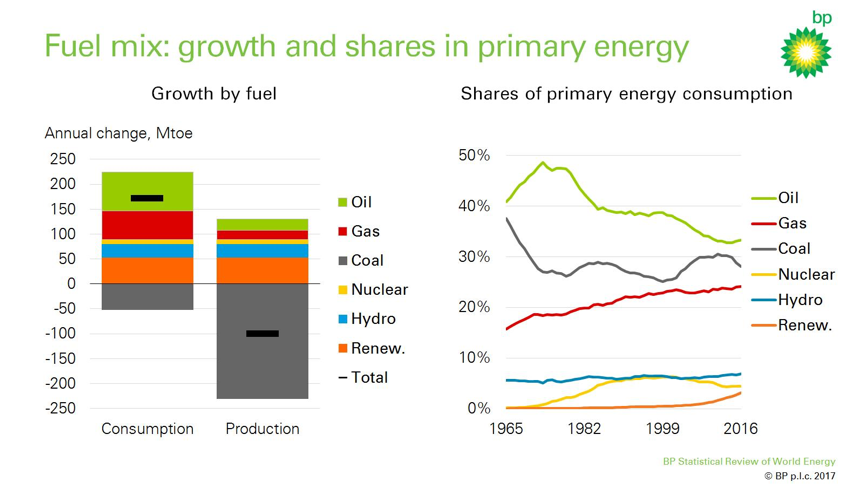

- Renewables was the fastest growing energy source, up 12% in 2016, accounting for nearly a third of the increase in primary energy despite having a share of only 4%, but coal fell sharply for the second year by 1.7%.

- Weak demand growth and gains in energy efficiency meant that carbon emissions remained flat in 2016, for the third year in a row, but a contributor to this may be the slowdown in China’s economy.

Nevertheless, despite this slowdown China remained – yet again – the world’s largest market for energy.

But the slow growth in primary energy demand may be signaling a world in transition, with increases in demand driven by developing countries, while in developed countries demand remains flat.

BP Group chief economist Spencer Dale said: “This year’s Stats Review shines a light on both factors driving energy markets in 2016: short-run adjustments and long-run transition.”

As well as responding to the long-term transition towards low carbon energy, markets last year also had to respond to a series of shorter-run factors. This was most notable in the oil market, which continued to adjust to the excess supply that has weighed on prices over the past three years.

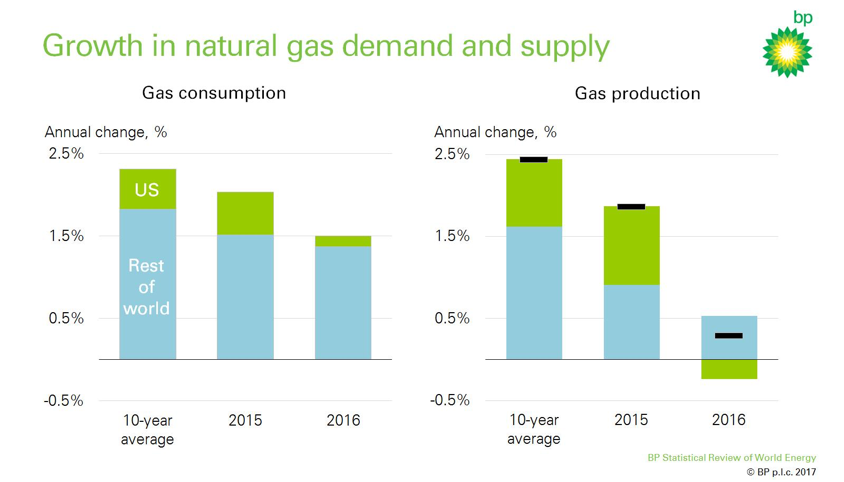

While the oil market has been adjusting to excess supplies, the natural gas market was relatively muted in 2016. Global demand rose by 1.5%, weaker than the 10-year average of 2.3%. Global gas production was essentially flat, up 0.3% – the weakest growth in gas output for almost 35 years, other than in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

What was notable in terms of the long-term transition towards low carbon energy was that 2016 was the third consecutive year of weak growth in global primary energy consumption and saw little or no growth in carbon emissions, on the back of strong growth in renewable energy and further decline in coal demand.

SUBHEAD: Primary energy

For the third year running, in 2016 global primary consumption was limited to just over 1%, slightly above 2015, with almost all growth coming from developing countries (Figure 1).

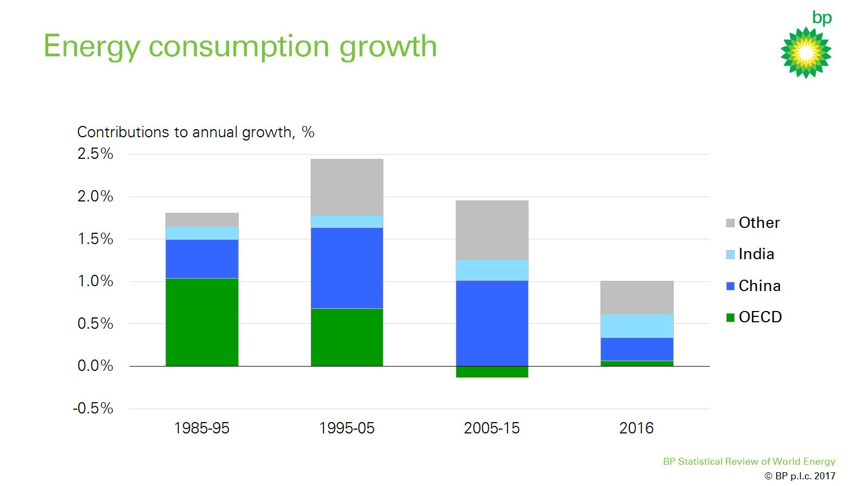

OECD growth was minimal, but nevertheless positive in comparison with the average slowdown during the past decade. This may reflect the fact that OECD economies are now experiencing growth, recovering from the 2008 slump.

But the strongest impact came from China, even though its contribution to global energy demand growth declined to about 0.25% in 2016, well down on the 1% average over the previous ten years. As BP explained, this is due to the slow-down in China’s economy, which may be reversed over the next few years. However, most forecasts expect China’s future energy demand growth to stay at or below 2%, and to start decoupling from economic growth in the 2020s.

Figure 1: Global primary energy demand and energy intensity

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017

Figure 2 Global primary energy consumption growth

As a result, the barely noticeable growth in global energy demand as seen during the last 3 years is likely to become the future norm.

As a result, the barely noticeable growth in global energy demand as seen during the last 3 years is likely to become the future norm.

Figure 3: Fuel share of primary energy consumption

The biggest user of primary energy is the power sector, using over 40% in 2016. It is the sector leading energy transition, with most technological improvements in energy efficiency and in the shift towards a low carbon energy future.

Global power generation grew by 2.2% in 2016, less than the average over the last ten years, with almost all growth coming from developing countries. Power demand in OECD countries has remained flat during the last three years, exhibiting a decoupling between power demand and GDP growth.

Oil demand up

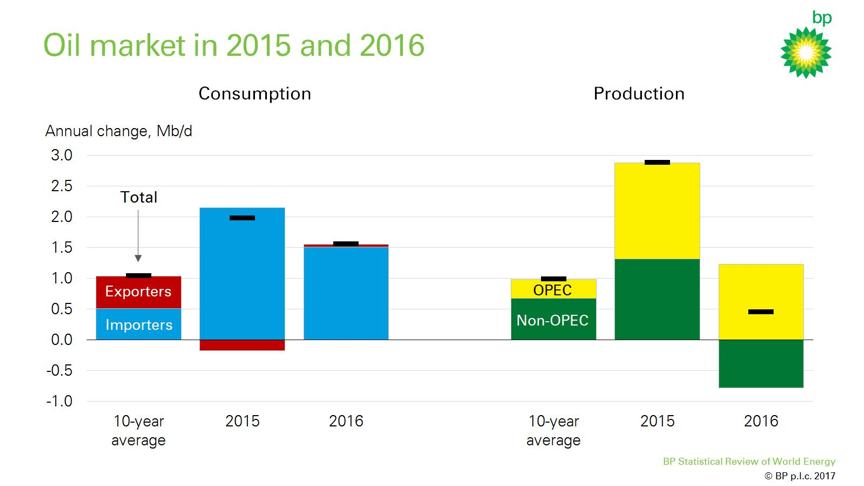

For the oil market 2016 was the year of adjustment, with oil demand increasing, even though at a lower rate than in 2015, and production growth slowing down in comparison to 2015 (Figure 4).

Most of the production growth came from Opec, with non-Opec producers experiencing their largest decline in 25 years, as low prices hit US shale oil production. Strong demand and weak supply brought the market into balance, but not sufficiently to absorb excess supply. As a result prices remain low.

The resilience of US shale oil was evident last year. It responded more quickly when prices went down, and bounced back even faster when prices went up, within a few months, in comparison to conventional oil. Shale also benefited from substantial reductions in costs, with break-even prices now averaging below $40/b, with more cost cutting expected.

Figure 4: Oil market in 2016

Once the market upheavals of the last three years subside, with oil demand growth outstripping production growth, oil inventories will start falling, probably during the second half of 2017 or in early 2018. In addition, the longer-term growth in oil demand is expected to slow-down. BP expects this to average 0.7%/yr to 2035, but others predict peak oil demand to occur between 2025 to 2035, if not earlier.

Natural gas demand grows

Natural gas demand rose in 2016, by 1.5%, but at a lower rate than in 2015 and the last ten years; and net production was almost flat, at 0.3%.

Most of the fall in production is due to low gas prices, but it is also associated with the slowdown in US shale.

Henry Hub prices averaged about 5% less than in 2015, but European and Asian spot LNG prices were down by 20%-30% due to a glut in supply.

Figure 5: Growth in natural gas demand and supply

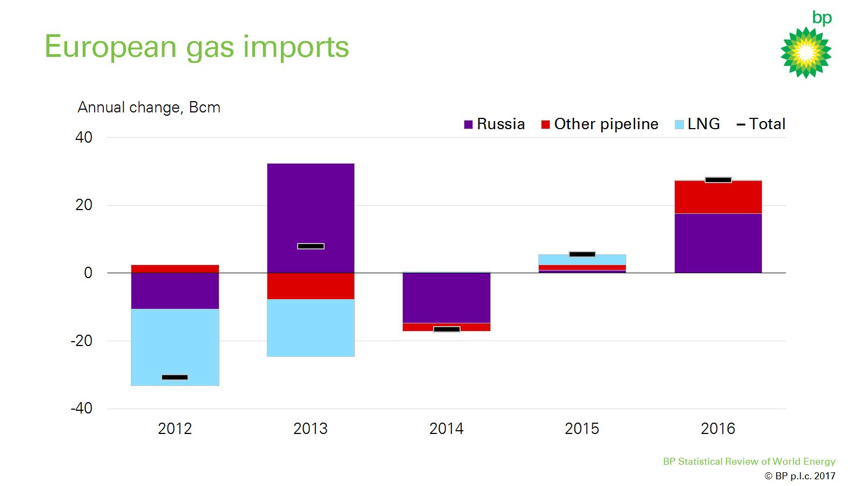

However, gas demand in Europe rose strongly, by 5.9% (Figure 6), helped both by the increasing competitiveness of gas relative to coal, and by weakness in European nuclear and renewable energy.

Europe’s access to plentiful supplies of pipeline gas, particularly from Russia, means that LNG imports are facing stiff competition. In terms of this one-sided battle of competing supplies, 2016 went to pipeline gas. The increase in European gas demand was met mostly with gas from Russia and Algeria, with LNG supplies remaining flat. Russia has a strong incentive, but also the capacity, to compete to maintain its market share in the face of growing structural competition from LNG supplies. However, Europe has the option of importing LNG as and when the need arises.

Figure 6: European gas imports

LNG production grew rapidly in 2016, with global supplies set to increase by a further 30% by 2020. As Dale observed, this is equivalent to a new LNG train coming on stream every two months until the end of this decade. In addition to low prices, this is leading to a shift towards more flexible trading, shorter and smaller contracts and increased spot trading. These are likely to lead to more integrated global markets.

Increasing availability of LNG supplies prompted a number of new countries, including Egypt, Pakistan and Poland, to enter the market in the past couple of years. New markets are also benefiting from the increased flexibility offered by FSRUs.

Coal market

According to BP an obvious loser in 2016 was the coal market. As can be seen from Figure 3, coal demand fell 1.7% in 2016. And it did so for the second year running.

Dale was careful to observe: “The speed of deterioration in the fortunes of coal over the past few years has been stark: it’s only four years ago that coal was the largest source of global demand growth. I’m sure there will be further ups and downs in the fortunes of coal over coming years, but the scale of the declines in recent years do seem to signal a fairly decisive break from the past.”

But articles that appeared following the BP presentation were quick to call this event signaling ‘the demise of coal’. It is far from obvious that this is the case.

Coal has been experiencing ups and downs over the last 40 years, with its contribution to global primary energy varying in the range 25% to 30%, averaging 27%. The variability during the last two years has been well within this range, with the 28% contribution in 2016 above the long-term average.

The ‘break with the past’ has more to do with the fact that coal is no longer the number one fuel and demand not increasing, but it is remaining more or less flat. Even BP’s Energy Outlook 2017 expects the share of coal in global primary energy to remain at about 24% by 2035 (NGW Vol 2, Issue 12).

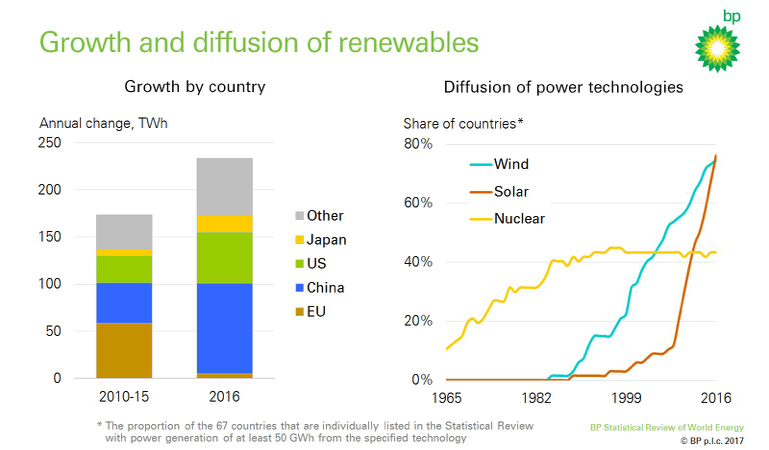

Renewables and carbon emissions

The growth of gas, and coal, has been squeezed by the increasing contribution from renewable energy. One noticeable weak spot last year, though, was the EU, where renewable energy barely grew as load factors in both wind and solar fell back from unusually high levels in 2015. The experience of the EU last year is a reminder of the variability that weather conditions can inject into renewable energy generation from year to year.

China dominated 2016, contributing 40% of global growth, surpassing the US (Figure 7). Renewables grew by 12% in 2016 in comparison to 2015, but provided about 7.5% of global power generation and 4% of global primary energy. However, this growth in renewables represented almost a third of the 1% total growth in primary energy demand in 2016.

Figure 7: Growth of renewables

China also accounted for most of the 1.3% growth in global nuclear power. Hydroelectric power generation rose by 2.8% in 2016.

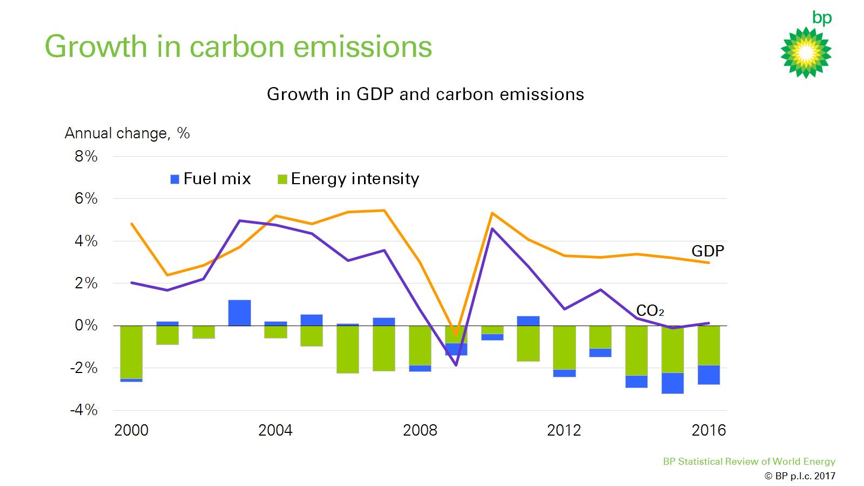

The slow growth in global primary energy, the decline in coal consumption and the increase in renewable power generation all helped keep carbon emissions flat in 2016, for the third year running (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Growth in carbon emissions

But much of this slowdown in carbon emissions over the last few years can be traced back to the fundamental changes in the Chinese economy and their energy consumption. Dale said: “Some of this slowdown reflects weaker GDP growth, but the majority reflects faster declines in the carbon intensity of GDP – the average amount of carbon emitted per unit of GDP – driven by accelerating improvements in both energy efficiency and the fuel mix.”

But is this a break from the past that will soon start producing significant reductions in global carbon emissions, in line with recommendations in recent reports, such as that by Statoil and by the joint IEA/Irena report? These state that immediate action is needed to transform the global energy system if the 2degC target is to be achieved. Or could it be due to short-term cyclical factors that may unwind over time, and to a combination of both.

It remains to be seen. Dale concluded: “We still have a very long road in front of us to get to Paris. We must retain our focus and efforts on reducing carbon emissions.”

Charles Ellinas

Graphics Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2017

This article is featured in NGW Magazine Volume 2, Issue 13