Biomethane is the Future [Gas Transitions]

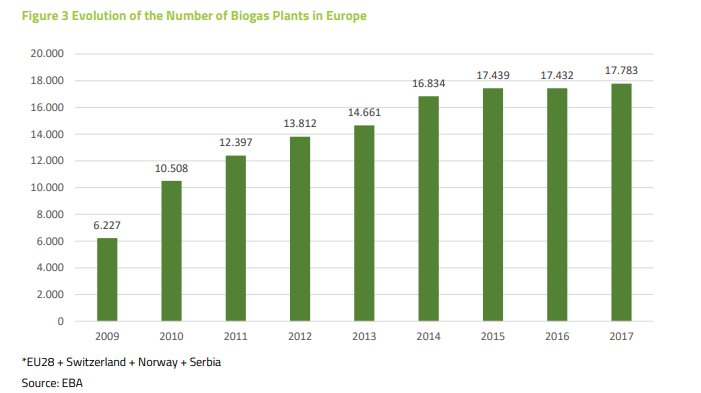

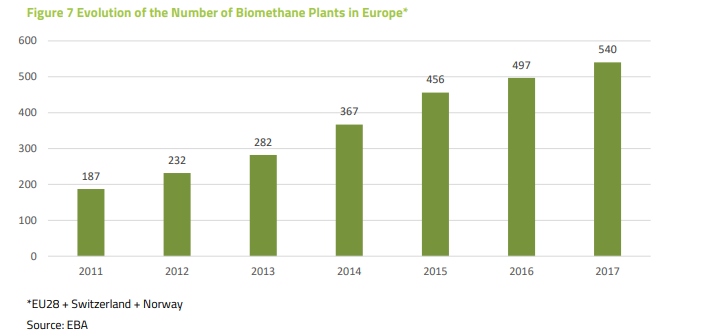

The number of biogas plants in Europe reached 17,783 by the end of 2017, almost three times as many as in 2009, but only 2% higher than in 2016. The number of biomethane plants grew to 540, 9% more than the year before, and nearly three times as many as in 2011. These figures are reported in the latest edition of the annual Statistical Report on biogas published by Bioenergy Europe in conjunction with the European Biogas Association August 8.

The Statistical Report gives numbers for biogas and biomethane up to 2017. Biomethane is biogas upgraded (mainly by removing CO2) to reach a high methane content (over 96%), so that it can be used as a direct substitute for natural gas in the grid or in trucks, cars and ships.

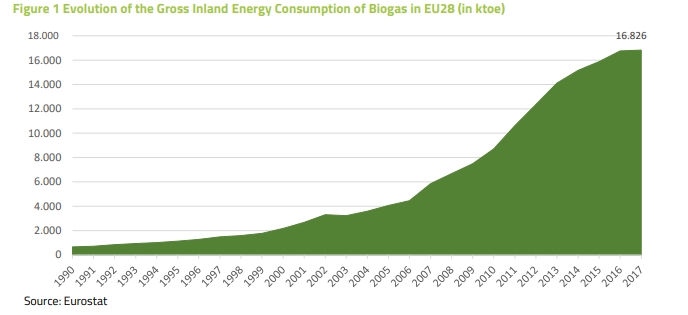

In terms of volume, the consumption of biogas has “increased tremendously since 1990 and has been multiplied by a factor of 25”, notes the report. The increase “was supported by the fast development of advanced technologies, resulting in higher plant efficiency, cheaper digesters as well as cheaper upgrading units used for the conversion of raw biogas to biomethane of a natural gas grade.”

Note that the number for 2017 is 16826 ktoe (sixteen thousand eight hundred and twenty-six) = 18.7 bcm. The numbers for biogas do not include biomethane.

Nevertheless, biogas represented only 1% of total gross inland energy consumption in the EU28, and just 4% of natural gas consumption. “In light of this, it is clear that there is still the possibility for a large increase of biogas usage and a real need to promote this bioenergy as one of the reliable solutions for a low-carbon energy transition”, notes the report.

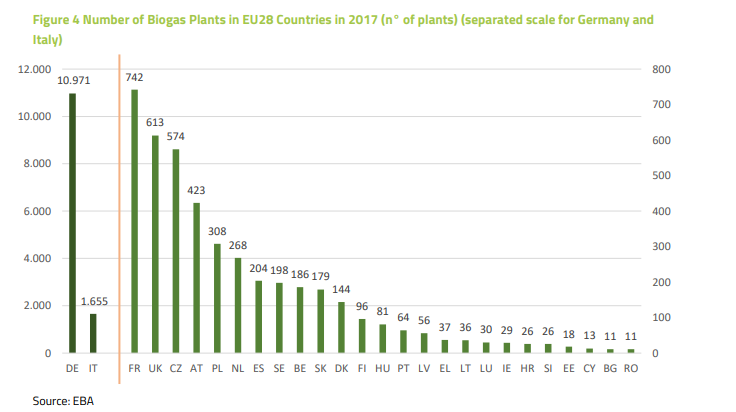

The slow growth in biogas production in recent years is mainly due to legislative changes in Germany, by far the largest biogas market in Europe. As a result of new EU rules, German biogas plants no longer benefit from a feed-in tariff, but have to participate in tenders. By contrast, growth in France and the UK has continued, according to the report.

Landfill and sewage gas accounts for around 24% of total biogas production, the rest of it comes mainly from anaerobic fermentation of agricultural feedstock (manure, crops, and agricultural residues). The report notes that “the utilisation of agricultural residues such as manure is particularly important in countries such as Denmark, France and Italy. This underlying growth in synergies between animal farming and biogas provides a profitable manure management solution. Energy crops such as maize, silphium or sorghum are largely used in Germany and Austria.”

Municipal organic waste is still “underrepresented”. Similarly, thermal gasification (pyrolysis) of biomass (wood residues) accounted for just 1.3% of total biogas production.

One thousand biomethane plants

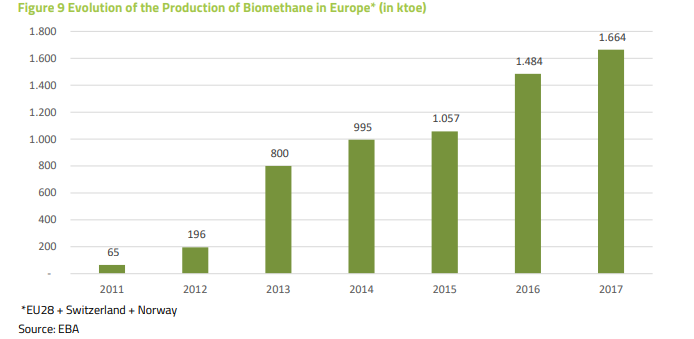

The production of biomethane rose by some 12% in volume in 2017 compared to the year before, reaching the equivalent of 0.42% of the natural gas consumed in Europe:

Note that the number for 2017 is 1664 ktoe (one thousand six hundred and sixty four) = about 1.8 bcm.

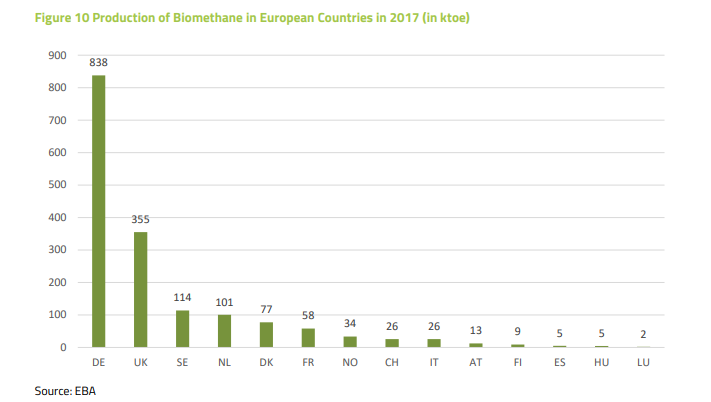

Despite strong growth of biomethane production in France, Germany is still market leader in Europe:

In France 18 new biomethane plants were constructed in 2017 and 23 additional plants were built in 2018, reaching a total of 67 biomethane plants. France has highly favourable policy conditions for biomethane production. The country is attempting to reach 1,000 biomethane plants injecting its gas into the national gas grid by 2020, according to the report.

A lot more interested

Harm Grobrügge, who became President of the European Biogas Association (EBA) in March 2019, tells NGW he is “very optimistic” about the future of biogas and biomethane in Europe – especially the latter. “Biomethane is where our future lies,” he says.

Biomethane has the advantage over biogas that it can be used in transport and can be inserted directly into the gas grid, since it has the same quality as natural gas. He mentions Sweden and France as countries with exemplary policies.

“Sweden has chosen a unique policy, focused purely on the transport sector”, says Grobrügge. “This is a very attractive market. Electrification will be difficult to achieve in heavy transport and shipping. Biomethane is a cost-competitive alternative in this segment.”

The Italian biomethane sector is also a “forerunner” in the transport sector, notes Grobrügge. “They already have a lot of CNG cars in Italy. Italian oil producers, who have to meet certain renewable fuel standards, have agreed with the biomethane producers that they will pay the feed-in premium for the biomethane .”

Grobrügge believes that the supply of biogas and biomethane could be an opportunity for countries like Russia and Ukraine

France has chosen a different route. “They originally started producing biogas to produce electricity and heat in CHP units, but then they decided to switch to biomethane production, which will be fed directly into the gas grid. What is unique about this initiative is that the natural gas companies in France are one of the drivers of this. They have said they want to reach 100% biomethane in the gas grid sometime before 2050.”

In the UK, biogas is showing healthy growth after a difficult period, says Grobrügge. “The UK concentrates on food waste as feedstock. The problem was that farmers were not so happy with the digestate, which is a by-product of biogas production and is used as manure. The plant operators have now started to put biogas plants on the farms and getting the farmers financially involved. That has made them a lot more interested.”

Not standing still

The German market, although it is by far the largest in Europe, is currently struggling a bit, says Grobrügge, who owns a farm with a biogas plant in the northern part of the country, and so has first-hand experience of how the market works. But he believes the stagnation in Germany will be temporary and is actually not such a bad thing. “Under EU rules we have changed from a feed-in tariff to a tendering system. This is a hurdle for small producers especially, like myself. But maybe the German market had grown a bit too fast anyway.”

German biogas producers have been criticized because they mostly used maize, a food crop, as feedstock, Grobrügge explains. “We are now changing from maize to straw and other agricultural wastes. That means we have to invest in new equipment. We are also putting money into CHP units so we will be able to produce more electricity in future compared to gas. This way we will be able to position ourselves as flexible electricity supplier in times when there is insufficient solar or wind power. That’s where we see a lot of potential in Germany. So production may not be growing but we are not standing still.”

Grobrügge is quite happy with the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED-2), which the EU adopted in December 2018. This establishes a binding renewable energy target for the EU for 2030 of at least 32%. “This will give a great boost to renewable gases once the Directive is transposed into national law in the member states.”

"As a farmer I see we have overproduction all over Europe. Why not use it to produce energy?"

One of the consequences of the new Directive is that farmers all over Europe will be able to use manure for biogas production. “The RED2 finally acknowledges that manure treated in anaerobic digestion not only has a positive CO2 effect as far as the energy produced is concerned, it also takes into account that untreated manure emits methane during open storage”, explains Grobrügge. “That is why there will be a CO2 credit for manure treated in biogas plants of up to 200%. We expect that this will lead to a significant rise in the use of manure for anaerobic digestion.”

One technology that is not progressing very well at the moment is gasification. This is used especially for wood, which cannot be fermented very easily. “There are some big gasification plants in Europe, for example a 20 MW plant in Gothenburg in Sweden. They are much bigger than the biogas and biomethane plants. But they are not operating, because they are not financially viable. Gasification is fairly complex.”

Decrease in consumption

How far could biogas and biomethane grow in Europe in the longer term, according to Grobrügge? “That will depend largely on agricultural policy in Europe”, he says. So-called “energy crops” are controversial, although Grobrügge believes the criticism is sometimes unfair. “As a farmer I see we have overproduction all over Europe. We are dumping our excess production in the developing world, where we undermine their agriculture. Why not use it to produce energy in Europe? I believe this should be part of the solution.”

The EBA President also believes that the supply of biogas and biomethane could be an opportunity for countries like Russia and Ukraine. “They have difficulty in exporting their agricultural products to Europe at the moment. This is because it is cheaper to import grain from Argentina by ship than from Ukraine and Russia by truck! If they convert their produce into biogas they can feed directly into the European gas market.”

Eventually, all of the gas used in Europe will have to be “renewable”, says Grobrügge. This will include “power-to-gas” in the form of hydrogen or methane. “We are part of the Gas-for-Climate initiative, which shows how Europe can decarbonize its energy system with a major contribution from renewable gas”, notes Grobrügge. (See this article on Gas Transitions.) “This scenario shows a positive future for gas. That is ground for optimism. But”, he adds, “apart from an increase in production of renewable gas it also shows a considerable decrease in consumption. People tend to forget that sometimes.”

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com