Asia-Pacific will need a lot more gas

This was the clear message at the Singapore International Energy Week (SIEW) conference in October. Asia-Pacific – Asia excluding the Middle East – will need the gas during the energy transition to help it move from coal to renewable sources of energy.

This is backed by many published, credible, outlooks. BP’s Energy Outlook 2023 New Momentum scenario -based on current trends and known policies- expects global gas consumption to increase by more than 20% by 2050, with almost three-quarters of this growth driven by increasing demand by Asia-Pacific countries.

This was also supported by a new UN report, The Production Gap - Phasing Down or Phasing Up. Even though the report was produced to draw attention to the impact of the use of unabated fossil fuels on emissions, it says that based on current government plans natural gas production is on track to increase by a third by 2050.

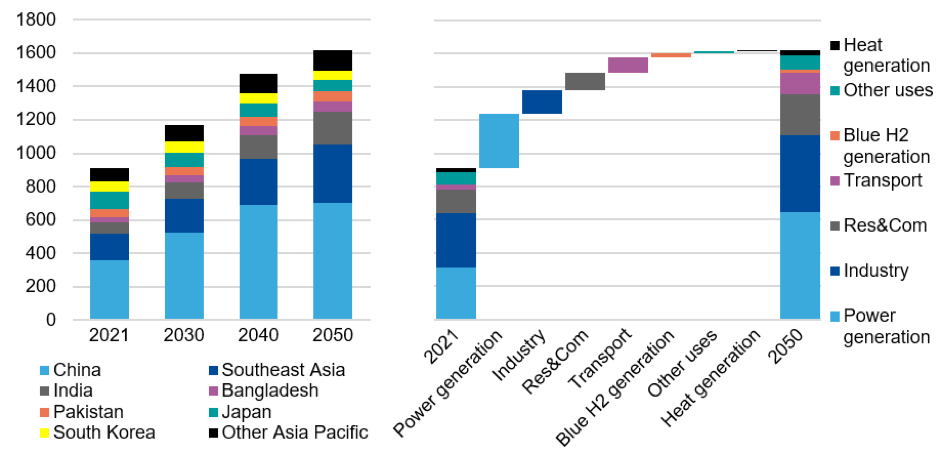

The latest edition of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF)’s Global Gas Outlook 2050 states that the growth potential for natural gas demand in Asia-Pacific is huge, estimated at 710bn m3 between 2021 and 2050 (see figure 1). This will help the share of gas in the primary energy mix rise from 12% to over 16% by 2050.

These messages are in contrast to the International Energy Agency's (IEA) annual World Energy Outlook report also released in October. Its STEPS scenario expects global natural gas consumption to peak by 2030 and remain flat all the way to 2050.

Messages, such as IEA’s, that this is the beginning of the end of natural gas, could deter investment in longer-term gas projects. Lack of realism, recognising that gas will be needed all the way to 2050 to support renewables during energy transition, will only lead to supply shortages and crises down the road.

With Asia-Pacific expected to account for about half of global energy consumption by 2050 and many countries looking to gas to support energy transition, the region’s needs for new, reliable, supplies are very real.

What drives gas demand growth in Asia-Pacific

As GECF points out, what unites countries in Asia-Pacific is a “strong policy push to improve air quality, along with reducing greenhouse emissions.” That requires cutting coal dependence, paving the way for a substantial increase in natural gas use.

With concerns over air quality, China in particular is targeting to increase the share of natural gas in its energy mix from 8.5% in 2021 to 15% in 2030. Similarly, India is planning to increase gas usage from 6% now to 15% by 2030. Much of this will come from LNG.

In addition, the recent energy crisis demonstrated that renewables are not yet sufficiently reliable unless backed up by dispatchable sources of electricity, notably natural gas.

Thus, gas-based power generation will be in demand to provide dispatchable capacity and energy security in support of the integration of the growing share of intermittent renewables.

Asia-Pacific accounts for over 80% of global coal consumption and it provides close to 50% of its primary energy. At present, natural gas provides only about 12% of Asia-Pacific’s primary energy and renewables -solar and wind- even less at just over 7%. Clearly there is a huge potential for coal to gas switching, while the use of renewables grows during energy transition.

GECF states that gas demand in the industry and in the residential and commercial sectors will also rise considerably, recording 20% and 14% of total growth respectively (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Asia-Pacific natural gas demand by country and sector (bn m3)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

Need for new investment

Outlooks, other than IEA’s, expect demand for gas as a bridge fuel in the energy transition to be enduring well into the future, requiring fresh investments.

The International Gas Union (IGU) warns in its new annual Global Gas Report 2023 that without new investment in exploration, production could decline by 75% by 2050 due to asset maturation and natural decline, leading to “more severe and frequent price shocks than those of the past two years.” “A high level of misalignment between supply needs with policy and financial developments, creates a high level of risk of future supply imbalances.”

IGU is warning that “restoring a sustainable balance in the global gas market is imperative and requires addressing the existing supply shortfall, an outcome of a prolonged under-investment period. Investment levels in gas supply development were reduced by 58% in the period between 2014 and 2020, and only started to marginally recover in 2021.”

In response to the growing demand for gas and LNG, Asia-Pacific is expected to lead in gas infrastructure spending between 2021 and 2050, especially in new LNG regasification facilities (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Midstream gas investment by region 2021 to 2050 ($bn)

.png)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

About 80% of this investment is expected to be allocated to LNG regasification infrastructure.

But China is also pursuing pipeline gas. Early November Gazprom, China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) and PipeChina reached agreement on the design and construction of a 10bn m3/yr cross-border pipeline in the Far East, with start-up scheduled in early 2027. China, Russia and Mongolia are also in the process of negotiations for the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline.

More LNG

The message at SIEW was that Asia-Pacific remains bullish on the future of gas and LNG demand to meet increasing power consumption while transitioning to net-zero by 2050. According to Woodside Energy, “demand for oil and natural gas will stay resilient for decades, driven by population growth and industrialization in developing economies across Asia… Growth in demand for LNG in particular is expected to continue as buyers seek to secure supplies to support renewables in the power mix as they decarbonise.”

LNG remains attractive as government officials in the region are concerned that intermittent renewables are not reliable to meet regional energy needs, requiring more flexible back-up. But they are also concerned about LNG pricing volatility and affordability.

However, with a massive increase in LNG capacity, expected to increase by 40% between now and 2030, prices are expected to come down making LNG a more competitive fuel.

Based on data from GECF, global liquefaction capacity is expected to more than double, potentially increasing from 478mn tonnes/year in 2022 to well over 1000mn t by 2050.

Asia-Pacific is getting ready for this with a massive expansion in LNG regasification terminals, expected to add 650bn m3 new capacity between 2023 and 2027. This is a whopping 70% of all capacity additions worldwide over that period.

About a third of this will be in China. As gas/LNG supply improves, China’s coal-to-gas switching plans will get back on track. This is important to the country’s 14th Five-Year Plan, which puts emphasis on both sustainability and energy supply security in support of its pledge to become carbon-neutral by 2060. In preparation, China continues to build new regasification capacity at a fast rate.

China overtook Japan to become the world's largest LNG importer in 2023 and is expected to account for close to 50% of Asia-Pacific’s incremental gas consumption between to 2050.

Asia-Pacific dominates

Despite the decreasing cost of renewables and LNG price fluctuations, Asia-Pacific dominates expansion of natural gas, led by China. The driving factor is the need for reliable and secure energy.

Increasing geopolitical risk has become the most significant driver of the massive expansion in LNG trade. As Lorenzo Simonelli, CEO Baker Hughes, said in an interview in The FT in November, gGeopolitical risks are at their highest level in half a century, raising concerns about energy supplies and helping to fuel a boom in LNG.” He added that “LNG has helped cut emissions by replacing coal as a provider of baseload power and it would continue to be part of the energy mix for years to come.”

It became clear at SIEW that Asian energy importers and policymakers, led by China, want a lot more gas and LNG, with demand expected to double by 2050, defying IEA expectations that global natural gas consumption will peak by 2030.

Wider adoption of carbon capture and storage and getting into grips with methane emissions, will strengthen the case for gas and LNG even further.