A sense of proportion [NGW Magazine]

Having adopted the goal to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, with a 2030 target to reduce emissions by 55% on the way, the European Union (EU) is now focusing on methane emissions.

The European Commission (EC) presented its strategy October 14, following a period of consultation that started in March this year.

The EC is taking decisive steps to reduce methane emissions. And it is just the beginning. The strategy states: “While in the short-term, the strategy encourages global level voluntary and business-led initiatives to immediately close the gap in terms of emissions monitoring verification and reporting, as well as reduce methane emissions in all sectors, it foresees EU level legislative proposals in 2021 to ensure widespread and timely contributions towards the EU decarbonisation objectives.”

Energy commissioner Kadri Simson said: “We have adopted today our first strategy to tackle methane emissions since 1996. While the energy, agriculture and waste sectors all have a role to play, energy is where emissions can be cut the quickest with least costs. Europe will lead the way, but we cannot do this alone. We need to work with our international partners to address the methane emissions of the energy we import.” The biggest of these partners include Russia, Algeria and the US.

The strategy “identifies a set of actions that will achieve significant reductions… at EU and international level.” To put the magnitude of the problem in context, in the EU 53% of anthropogenic methane emissions come from agriculture, 26% from waste and 19% from energy.

But while the strategy places the energy sector in the spotlight, it lacks detail for agriculture and waste. The EC admits that its climate target plan impact assessment indicates that, with prospects to limit methane emissions in agriculture more limited, the most cost-effective savings can be achieved in the energy sector. Nevertheless it provides a much needed framework to deal with a problem that gravely tarnishes the “clean” image of natural gas.

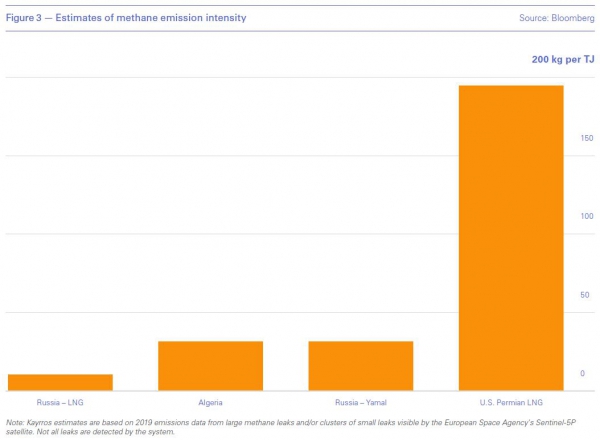

Methane emissions from the oil and gas sector are summarised in Figure 1 based on data from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The IEA states that the oil and gas industry could cut emissions by three quarters using technology that is available today. Moreover, more than half of this is achievable at net-zero cost.

The European gas industry has responded positively, committing to embrace the new strategy and to play its part in achieving the climate neutrality goal by 2050, provided that enabling measures are implemented.

Eurogas’ secretary general James Watson told NGW that its “members are committed to limiting methane emissions in their networks and will continue to work with European decision-makers on, and implementing, best practices. In fact, a broad range of actions is already being undertaken on this front through the Methane Guiding Principles – a voluntary initiative aimed at exchanging best practices and strengthening the management of methane emissions throughout the industry. He went on to say: “Eurogas and many of our members are part of this initiative. For example, just earlier this week [on 10 November] Eurogas and Wintershall Dea held a joint webinar on the impact of the EU Methane Strategy on gas. We aim to have more events like this in the future to share knowledge and exchange best practices on tackling methane emissions.”

Under current policies, methane emissions in the EU are projected to be reduced by 29% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. But the strategy states that the new target to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 55% by 2030 in comparison to 1990 levels implies a step-up in methane emission reductions by 35% to 37% by 2030 compared with the 2005 baseline.

The strategy also states that in the absence of significant commitments from international partners, the EC will consider proposing legislation on targets, standards or other incentives to reduce methane emissions from fossil energy consumed and imported in the EU, including both pipeline and LNG.

Europe imports about 47% of internationally traded natural gas and LNG, making it the largest customer worldwide. This gives it huge leverage to make a global impact, even though it contributes only 5% of global methane emissions and 9% of CO2 emissions.

Impact on LNG imports

LNG exporters are becoming increasingly aware of the consequences of the strategy. Presumably under pressure from minority shareholder the French government, Engie pulled out of a $7bn deal with NextDecade to import US LNG. Ireland is also reportedly against imports of US LNG, given the fracking that enabled the upstream gas production.

Environmental deregulation has been a part of US president Donald Trump’s efforts to encourage self-sufficiency in oil and gas. He has eased emission limits and control requirements. So while production may be up, LNG exports have been tainted with a ‘dirty’ image in Europe, which is beginning to undermine it. And this at a time when imports of US LNG to Europe are at record levels, having increased from close to zero in 2016 to about 20bn m³ in 2019.

The new strategy cannot – yet – impact the US LNG industry, or any gas exporter to Europe for that matter, because it does not include specific restrictions on such imports.

But there will be emission targets or more stringent standards next year. The position taken by the French should be seen as a warning shot to exporters of gas and LNG to Europe to clean up their acts.

However, the EC may find a partner in its drive to reduce emissions in the shape Biden. Unlike his predecessor, his administration is expected to introduce stringent regulations to eliminate methane emissions from oil and gas facilities. This could include legislation to prohibit routine flaring and venting.

One of the first actions of his presidency will be to bring the US back into the Paris Agreement and work with Europe towards the COP 26 conference late next year. In preparation for that he is likely to make additional climate change pledges, including a 2030 emission reduction target and joining the ‘net-zero emissions by 2050’ club.

Natural gas will have a role to play in Biden’s plans but it will need to become cleaner. It will need to deal effectively with methane emissions and to be decarbonised. Biden’s plan includes commitment to develop ‘carbon capture and storage technology’ (CCS) and to provide incentives to accelerate deployment.

Eurogas also told NGW: “LNG is now being discussed more than ever at European level, as Europe is receiving record volumes of LNG in its facilities. In the frame of the Green Deal, LNG will do a lot more than just enable the switching from coal and oil. It will also reduce a lot of the air pollutants that are highly detrimental to health. So, LNG will play an important role not just in providing flexibility and diversity of supply, it will also result in CO2 reduction and improved air quality.” He suggested that “LNG terminals can also be transformed into dealing with bio-LNG or into liquid hydrogen, which can be shipped.”

Europe’s majors Shell and Total have already shipped carbon-neutral LNG cargoes, through the use of offsets such as afforestation. But there are limits to the amount of land that can be used in this way.

Major oil and gas companies, such as Shell, BP and Total, have already set targets to reduce the intensity of methane emissions from their operations. They are planning to reduce these to less than 0.20% of the commercial gas they produce. This may become the industry standard.

Detecting the invisible

The EU is determined to drive LNG-related methane emissions down as part of its net-zero goal. Accurate measurement technology will be essential to monitor the success of achieving emission targets. Relevant legislation for compulsory measurement, reporting and verification of energy-related methane emissions is expected to be proposed in 2021. It is likely to be based on the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) measurement and reporting framework.

Exporting natural gas to Europe, and possibly to other major users, will soon require low methane emission certification and proof that real efforts to reduce methane emissions are being made.

One of the priorities under the strategy is to improve measurement and reporting of methane emissions.

Europe is now able to detect methane emissions using its satellite Sentinel-5P in co-operation with Canadian company GHGSat’s satellites Claire and Iris. Claire’s resolution is 50 metres. Iris was launched on 2 September and can map methane plumes in the atmosphere down to a resolution of just 25 metres (Figure 2). This makes it possible to identify individual emission sources, such as specific oil and gas facilities, but data is not yet precise enough. Further development will be needed to improve reliability and accuracy.

Iris can show the concentration of methane in the air in excess of normal background levels at a region of Turkmenistan with oil and gas facilities.

Sentinel-5P scans the world every day with a resolution of 7 km, identifying regions and clusters with high emissions. Claire and Iris, with much higher resolution, can pinpoint individual facilities.

This has been of particular interest to the Climate Investments arm of the Oil & Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI), which is investing in GHGSat.

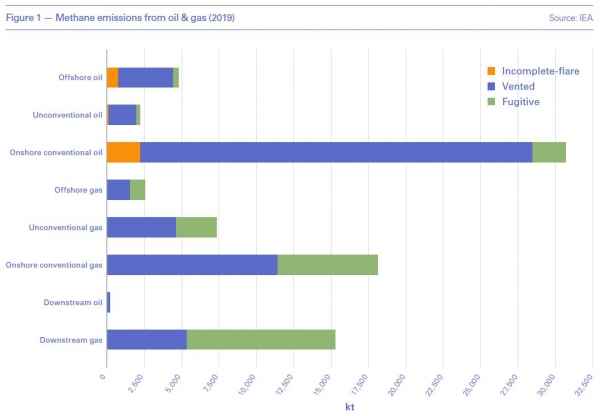

Using data from Sentinel-5P obtained in 2019, French analytics firm Kayrros SAS estimated the visible methane intensity from various parts of the world (Figure 3).

Data such as this reinforces European perceptions and concerns about US LNG and no doubt will form the basis of future discussions with Biden’s administration next year.

That is not to say that Russia and Algeria are doing well. In the longer-term all LNG exporters may benefit if they respond to EU methane emissions regulations and clean their act.

As part of its methane strategy, the EC announced that, in co-operation with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) and the IEA, it would support the establishment of an international methane observatory to collect and compare data on methane emissions worldwide. The initial focus would be on the oil and gas sectors, but the EC wants to extend it to coal, waste and agriculture once more reliable monitoring is possible.

The objective will be to enable the identification and minimisation of methane emissions along the gas production and supply chain, including fugitive emissions, venting and flaring. This is needed to ensure that natural gas will play a significant role in the European energy system well into the future.

_f400x579_1606126065.JPG)