Methane emissions – make or break for natural gas [NGW Magazine]

Natural gas is the cleanest fossil fuel: it is abundant and most outlooks forecast a long-term future for it. But in the context of a global energy transition, methane emissions have become a reputational issue – both for producers and for gas.

The oil and gas sector accounts for about a quarter of anthropogenic emissions. Methane escapes into the atmosphere in three ways: accidental leaks; intentional releases – often unavoidable for safety reasons; and flaring, where natural gas is incompletely burned.

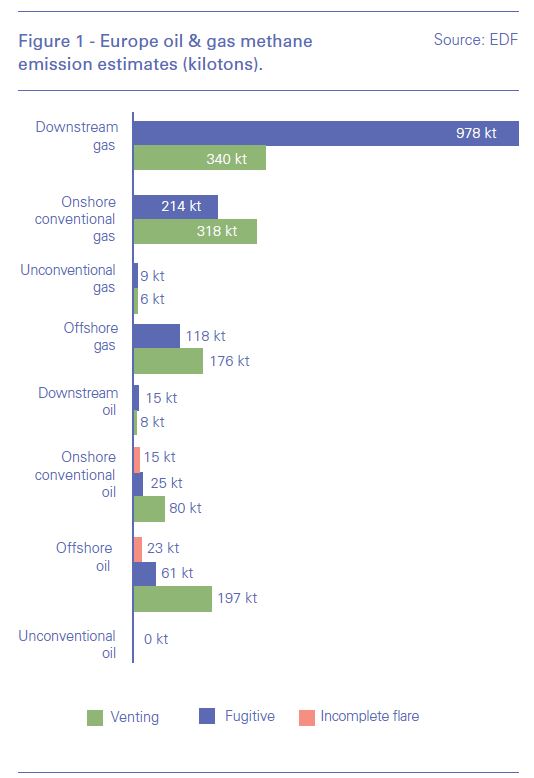

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) methane tracker (see box), based on 2017 data, EU domestic methane emissions from the oil and gas sector account for 3.3% of global methane emissions from that sector (Figure 1).

Methane is over 80 times more potent than CO2 over 25 years and 28 to 36 times more potent over 100 years. And as methane only lasts for about a decade in the atmosphere, actions to reduce methane emissions will yield benefits sooner than action to cut carbon dioxide.

The head of the UN Environment’s Energy and Climate Branch, Mark Radka, says: “The oil and gas sector, which is increasingly recognising the importance to act on climate change, can make a big difference by virtually eliminating methane emissions.”

Increased pressure

A new study published in Nature in February says that human-released methane could be 25% to 40% higher than was believed.

Most models of methane emissions assumed that a large proportion came from natural leaks unrelated to energy industry activity. But this new research shows that fossil fuel emissions form a much larger slice of the global methane pie than previously calculated.

The authors hailed this as positive news, as it means that humans are better able to control the problem and “placing stricter methane emission regulations on the fossil fuel industry will have the potential to reduce future global warming to a larger extent than previously thought.”

Dealing with gas flaring

Gas that comes with oil production is flared where that is the cheapest way to dispose of it.

The magnitude of the problem has expanded dramatically with the successful and widespread development of shale oil reserves in the US where there is a shortage of pipeline capacity. Based on available data, in 2019 as much as 810mn ft³/day gas were flared in the Permian Basin alone; and is likely to grow along with the oil. The US is now the world’s fourth largest flarer of natural gas, after Russia, Iraq and Iran – although the new oil price may act as a temporary brake.

The founding director of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University Jason Bordoff suggested in a recent article in the Financial Times that “industry leaders must recognise that abandoning the wasteful and damaging practice [of flaring] is in their self-interest.” He went further, saying “good intentions won’t be enough. Policy-makers need to penalise flaring to change behaviour.” He said a “flaring tax would sharply reduce the practice.”

Technologies exist

On average, 62% of methane emissions occur in the upstream sector, 5% mid-stream and 33% downstream.

Using generic data and modelling to estimate methane emissions is no longer adequate. What is needed is detail and actual measured data – reliable, verifiable, credible and accredited data.

All technologies are required to address the problem and they mostly exist:

- Satellites, aircraft, drones: to identify leak locations through gas cloud imaging (top-down);

- Ground techniques: to quantify leaks (bottom up);

- Analysis of data to quantify and eliminate leaks.

International Energy Agency head Fatih Birol told the IP Week conference in London that the energy sector is responsible for 75% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with 15% of these coming from the process of getting oil and gas out of the ground and to customers. Minimising these “should be a first order priority for all companies.”

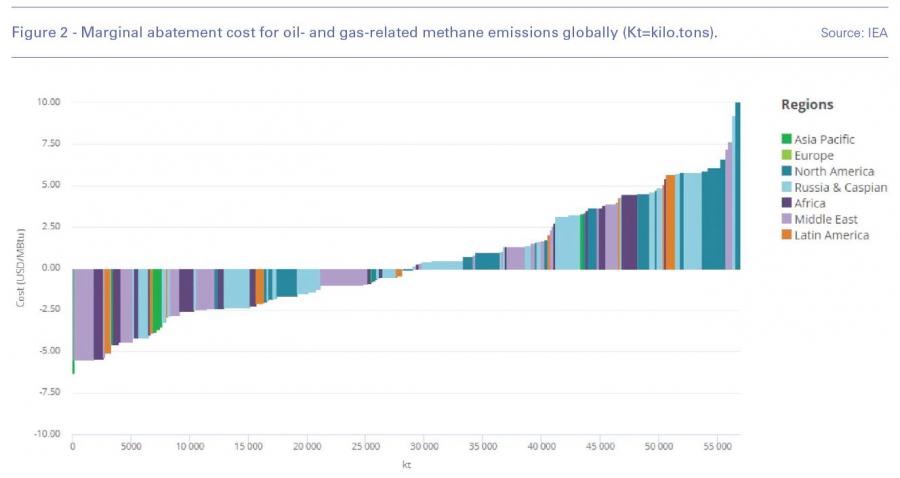

The IEA says that available technology can identify and eliminate 75% of methane emissions. Better than that, its work has shown that about 45% of them can be eliminated at zero-net cost because of the value of methane saved (Figure 2). This makes gas-related methane emissions the easiest to tackle.

IP Week is normally given over to the upstream and the national and international oil companies but this year was quite different, focusing on the energy transition. It was therefore a fitting forum for technology firms to show off their wares.

GHGSat said its high resolution satellites can be used to monitor methane emissions from oil and gas facilities, providing a ‘top down’ approach to detection. There exist satellites that “can address up to 70% of the total methane volume emitted from the source,” the company said.

Another firm presenting, The Sniffers, takes the opposite approach, using terrestrial techniques such as sensor equipment to detect and quantify emissions and energy losses from pipelines, for example.

Among the low-cost, technically feasible solutions are the recovery and use of escaping gas and reducing leaks from long-distance pipelines.

Sharper emission scrutiny will come through the availability of more accurate data, and this is where the industry is now concentrating its efforts.

For example, Anglo-Dutch Shell recognises uncertainties with methane emissions quantification and in order to reduce these it is rolling out a methane improvement programme. This focuses on further improving data quality and reporting, and roll-out of leak detection and repair programmes (LDAR) and methane abatement opportunities. By 2025, the plan is for all Shell-operated assets to have improved emissions data collection and analysis.

Identifying methane leaks and repairing them can be fairly straightforward, as a recent study in northwest Alberta, Canada, has shown.

It reported finding 969 leaks and 686 vents from 36 sites consisting of 30 well pads and six processing plants owned only by one company, Seventh Generation.

Seventh Generation participated in the project in order to be able to market its methane as cleaner than its competitors’.

Researchers spotted the leaks using special infrared cameras that capture methane clouds the eye cannot see, by carrying out optical gas imaging-based LDAR surveys.

After the leaks were identified, researchers carried out additional surveys and found 90% were successfully fixed. But they also discovered that “fugitive emissions reduced by only 22% because of new leaks that occurred between the surveys.”

The researchers therefore recommended the industry performs frequent and low-cost leak detection and repair surveys.

International initiatives

The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) is made up of 13 national and international oil and gas companies – although they represent only 30% of global oil and gas production.

They have committed to reduce by 2025 the collective average methane intensity of their aggregated upstream gas and oil operations by one fifth to less than 0.25%, against a baseline of 0.32%, with the ambition to achieve 0.20%. Methane intensity is the percentage of lost gas during oil and gas production, compared with the amount of gas sold.

The companies aim to work towards near zero methane emissions from the full gas value chain in support of achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement.

OGCI members reduced their collective average methane intensity by 9% in 2018, which led the group to confirm it was on track to meet the 2025 target of below 0.25%.

In 2019 OGCI formed a strategic partnership with Methane Guiding Principles (MGPs) and joined the Global Methane Alliance together with the United Nations and Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

The MGP is a multi-stakeholder collaboration that aims to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas value chain. Resources under development include a best practices tool-kit and education programme and principles for sound and effective methane policy and regulation.

During the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, UN Environment and the Climate & Clean Air Coalition called on governments to enhance ambitions in their nationally determined contributions by joining a Global Methane Alliance (GMA).

Depending on its actual methane emissions and the level of development of its own oil and gas industry, a country that joins the GMA will have a choice: it may commit to absolute methane reduction targets of at least 45% by 2025 and 60% to 75% by 2030; or to a near-zero methane intensity target.

These targets are considered to be realistic and achievable by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), which has committed to support member countries in this.

OGCI also sees the GMA as a unique opportunity to accelerate methane reduction and has confirmed that would provide technical support and knowledge-sharing to make it successful. Participating oil and gas companies will share knowledge, technologies, and best management practices.

So far 18 companies have signed MGPs and 10 organisations have pledged their support to them.

Developed collaboratively by a coalition of industry, international institutions, non-governmental organisations and academics, the MGPs focus on continually reducing methane emissions, advancing strong performance across gas value chains, improving accuracy of methane emissions data, advocating sound policies and regulations on methane emissions and increasing transparency.

The EC is actively involved in the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) led by the UN Environmental Programme. CCAC is involved in an ambitious methane emissions measurement and reporting framework, as part of the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP).

This is a voluntary initiative to help companies reduce methane emissions in the oil and gas sector and its partners include BP, Ecopetrol, Eni, Equinor, Neptune Energy, Pemex, Thai PTT, Repsol, Shell and Total – so there is overlap with OGCI.

In January 2020, OGMP members agreed to an updated framework to foster and encourage reporting that focuses on reduction approaches, and advancing technology and policy. The aim is to make “deep reductions in methane emissions over the next decade in a way that is transparent to civil society and governments.”

Europe’s Green Deal

Methane emissions reduction will be a key enabler of the European Union’s transition to cleaner energy. As methane emissions know no borders, international collaboration, including engagement with third countries and multilateral initiatives will be needed.

The problem is on the radar of the European Commission (EC) which is preparing proposals to cut them as it proceeds with the Green Deal.

EC deputy director-general Klaus-Dieter Borchardt told the European Gas Conference (EGC-2020) in Vienna that gas has a role to play in the short to medium term, but “we all need to work together to find solutions for methane leakage. We need better methodologies for measuring, reporting and certifying methane emissions transparently.”

The EC’s own position is clear: any talk of the long-term use of gas is pointless without dealing with methane emissions. There is a view that voluntary action is not enough on its own and regulations also have shortcomings on their own.

The EC is working on a first-ever methane strategy that could play a very significant role in enabling the EU increase its climate ambitions for 2030, but the exact timing of this strategy has not yet been confirmed.

As the EU’s methane strategy is a complicated task requiring involvement of all stakeholders, including the oil and gas industry, the latter has to make its case urgently and improve the quality of its reporting of emissions, as well as take measures to reduce methane emissions.

Challenges

Anyone who has attended more than a couple of gas conferences over the last six months, certainly in Europe, will be aware of the disconnect between the EC and the oil and gas industry.

The industry is taking concrete measures to address the problem, and this is generally the industry is good at – once it has identified a problem, it has the required capabilities to mobilise resources to deal with it.

Even ExxonMobil, long-considered to be a climate-change denier, is getting in in the act (see box). But as CEO Darren Woods has made clear, oil and gas will still be in demand during transition and the industry must defend this.

Echoing this, Russian Novatek CFO Mark Gyetvay said at IP Week the industry should "fight back" against its vilification by the green movement and stop apologising. It has made a "significant amount of effort to clean up our business." He added: "We have a challenge ahead of us where we need to bring more energy, not less." Referring to the green movement, he said. "We need to fight back and show the world that we're taking these steps. There is no dialogue today. There's only shouting and yelling on one side."

The message has not got through to Brussels and there are many activist NGOs on the other side of the fence who see natural gas as the ‘new coal,’ – even though unabated coal continues to generate electricity in Europe.

The IEA makes it clear that the industry is central to the success of energy transition. This is why the industry is an active participant in the public policy debate in Europe.

Oil and gas will not only be part of the equation during transition: according to the IEA, the “transformation of the energy sector can happen without the oil and gas industry, but it would be more difficult and more expensive.”

EDF says that a level playing field for gas and renewable electricity means addressing the life-cycle emissions of gas. As this article has shown, this is in hand. The industry is fully aware of the issues and it is addressing them, although it can never do so fast enough to satisfy everyone.

The curious thing is that there have been fewer attempts at addressing the obvious problems of renewable electricity-generation, particularly wind-farms and solar panels with their low-load factors at peak demand times and the economic damage done to baseload gas-fired plants through their intermittency, and so on.

And batteries are even more problematic: leaving aside market factors, they rely on rare earth elements, the mining of which produces large quantities of contaminated waste, they use toxic substances and have a high carbon footprint during manufacture, and as with wind-turbines, disposal is a problem.

A regulatory affairs executive at a European gas transmission company told NGW that, in his opinion, ‘Brussels’ had little interest in the damage that renewable industry did to the environment and had a clear pass, while gas needed always to justify itself.

A symptom of that might be the fact that battery vehicles are considered as zero emissions from the EC’s point of view: the electricity to charge them, even when it comes from fossil fuels, is not considered part of the equation. Biogas on the other hand, which is to all intents and purposes carbon neutral, is not.

But this is another matter. For gas, addressing and reducing methane emissions is key.

|

Industry takes action Aside from umbrella organisations, oil and gas companies have been setting performance targets and taking appropriate measures on their own account. UK major BP aims to reduce methane emissions from its operations by 50% by 2023, installing monitoring/measurement devices, such as cameras and lasers on its plant. About 70% of its methane emissions come from flaring – it is a big oil producer in the US – and 15% from operations. Only 5% are fugitive emissions. Anglo-Dutch Shell told IP Week that the energy transition process had to be ordered. “We need governments to provide a carbon pricing mechanism in whatever form works for them. We advocate that in every country we operate in," UK country head Sinead Lynch said. In 2018, Shell announced a target to keep its own methane emissions intensity below 0.2% by 2025. This target covers all oil and gas facilities for which Shell is the operator. In 2018, its methane intensity was 0.08% for assets with marketed gas and 0.01% for assets without marketed gas. Shell’s methane emissions intensity in 2018 ranged from below 0.01% to 0.9%. Italian Eni plans to cut its emission intensity by 55% between 2018 and 2050. According to its long-term strategic plan to 2050, it wants an 80% cut in net scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions – with reference to the entire life-cycle of the energy products sold – by 2050 and a 55% reduction in its emission intensity against 2018. Emissions from gas production will be offset through carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects. The approach to methane emissions in the developing world is far behind, but this is where companies and organisations such as IOGP come into play. ExxonMobil takes action The US supermajor ExxonMobil released a model framework for industry-wide methane regulations March 3. It recommends high-tech leak detection and prevention equipment, backed up by data gathering and the reporting of total methane emissions. So far it claims it has managed to reduce emissions from its US unconventional operations by a fifth. CEO Darren Woods said he hoped “this framework will be able to aid governments as they develop new regulations.” Unlike BP, ExxonMobil made a robust case for the future of oil and gas at the company’s annual investor day March 5, skewering the short-sightedness of companies who sell assets to another company so that their portfolio becomes greener. “This has not solved the problem for the world. It hasn’t made a dent in it. And in some cases, if you’re moving to a less effective operator, you’ve actually made the problem worse,” he said. An example might be the French utility Engie, which sold off its Asian coal-fired power assets in order to become greener as a primary consideration. Many other companies have made similar divestments with the same goal and with the same questionable environmental consequences. |

|

IEA and emissions The IEA gathered more than 60 members of various relevant industry, policy and regulatory bodies to “exchange views on ways to best step up efforts to regulate methane emissions from the oil and gas sector.” It is worried that the voluntary initiatives and commitments from policy-makers are not sufficient to meet the global climate goals outlined in the Sustainable Development Scenario. In order to meet these, methane emissions must be halved by 2025 and reduced by 75% by 2030 (Figure 3). IEA deputy executive director Paul Simons said the aim of the meeting was “to exchange views and lessons learned on what approaches work and what don’t work; what are the different considerations that have shaped regulation and enforcement in different jurisdictions around the world; and what can be done to support and widen these efforts.” The IEA said that over the course of 2020 to 2021, it will “make further advancements to its Methane Tracker with the aim of continuing to develop the tool to be useful for governments, industry and other stakeholders working to tackle methane emissions from the oil and gas sector.” The IEA also said that it plans to reconvene the network of experts within this timeline. |