Where is shipping going? [NGW Magazine]

The new regulations, introduced by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), will take effect on January 1. The current sulphur cap of 3.5% of total exhaust in most areas of open sea will drop to 0.5%. A limit of 0.1% in the Emission Control Areas (ECAs) along the EU and US coasts will remain.

The change will have major consequences for the global shipping industry. Just how smooth the transition might be, how much will it cost, and who will pick up the tab all remain questions.

The most viable options for shipping companies to reduce their sulphur emissions to meet the cap are to fit exhaust scrubbers, to switch to ultra-low-sulphur fuel oil, or to adapt their ships to use liquefied natural gas (LNG). However, the gas industry is struggling -- for the meantime at least-- to seal a major role.

Life Saver

The maritime industry carries 90% of all global trade, but is also responsible for 3% of carbon dioxide emissions, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation. This figure is expected to grow. However, the new regulations do not target CO2 but sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) which are produced by burning heavy fuel oil. These particles are linked to respiratory system symptoms and lung disease, as well as acid rain.

The reduction in the cap equates to a drop in sulphur content of 80-86%, according to a study by the Academy of Finland, which focuses on the direct health benefits of what it calls “the most significant improvement in global fuel standards for the shipping industry in 100 years”. The IMO estimates that the shipping industry contributes about 13% of the world’s sulphur-dioxide emissions.

Without the change, pollution from ships would contribute to more than 570,000 additional premature deaths globally in 2020-25. The new regulations will spark a reduction of 3.6% -- or 7mn cases/yr – in childhood asthma globally.

Shipping pollution is also estimated to contribute to 400,000 premature deaths/yr from lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. About one-third of these ship-related cardiovascular disease and lung cancer deaths will be reduced with cleaner fuels.

At the same time, the study suggests further regulation will be needed. “Shipping activity is expected to increase with global trade and continue to produce harmful air emissions and greenhouse gases,” it reads. “Despite the upcoming reductions, low-sulphur marine fuels will still account for approximately 250,000 deaths and 6.4mn childhood asthma cases annually, so more stringent standards beyond 2020 may be needed to provide additional health benefits.”

The general consensus is that the new regulations will cost the shipping industry around $50bn in the coming years, as it invests in the necessary technology to adapt engine systems to use cleaner fuels, which are expected to cost 25-40% more. The gas industry is facing off against oil and electricity to pump that fuel.

Runners and riders

Exhaust scrubbers are a solution most popular amongst larger vessels. These devices, which clean the exhaust gases with water, allow ships to continue using heavy fuel while meeting the regulations.

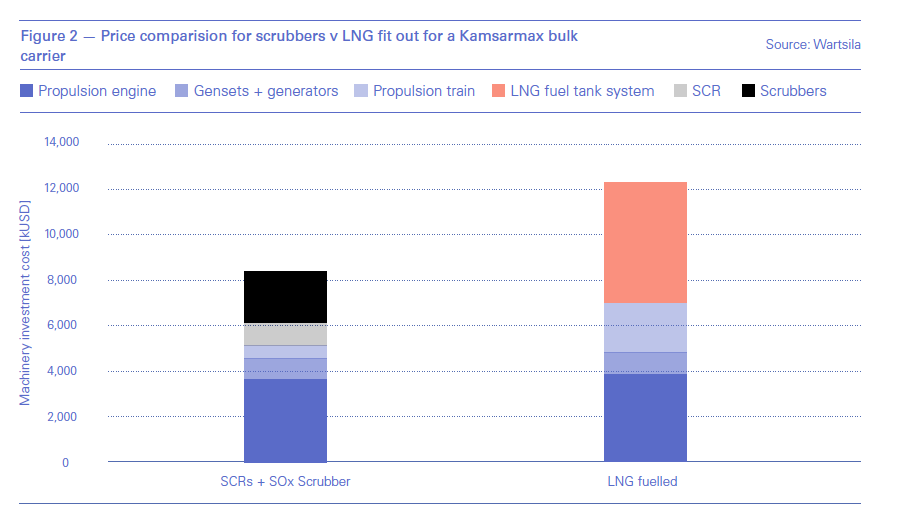

While that means vessels can benefit from the lower price of heavy fuel, the scrubbers themselves are expensive. A 2018 report by Japanese consultancy KBC estimates that fitting scrubbers costs $6mn - $10mn per ship.

In addition, there’s considerable uncertainty regarding future regulation of open loop scrubbers – the easiest type to operate – because they dump waste water into the sea. Some expect open loop scrubbers could be banned in the near future, especially given the IMO’s 2050 target of cutting carbon exhaust to 50% of 2008 levels.

Additionally, some argue that scrubbers are an inefficient industry model that makes little sense environmentally. Under this logic, the sulphur would be better removed at the refinery stage. Instead, individual ships will be converted into small factories that isolate the sulphur, raising their CO2 footprint.

Analysts expect that around 4,000 of the vessels in the global merchant fleet will have fitted scrubbers by the end of 2019 to try to comply with the new IMO regulations. A further 1,500 ships should be fitted out with the devices in the following twelve months.

That translates as around 15% of the global fleet by tonnage and 4.5% by vessel count, the global fleet numbering 90,000 ships.

These risks, combined with the up-front costs of fitting scrubbers, have persuaded analysts at investment bank ING that “the majority of ships, and in particular smaller ships, will switch to low sulphur fuels,” and the “majority” to ultra-low-sulphur fuel oils (ULSFO).

Much of the global fleet already uses ULSFO when travelling around the European and US coasts. Therefore, infrastructure in these busy areas is already established, with ports along these coasts facilitating ULSFO bunkering. However, it is widely assumed that refining capacity will limit a mass transition to ULSFO. There are also issues concerning the mixing of varying types of such fuel that complicate its use.

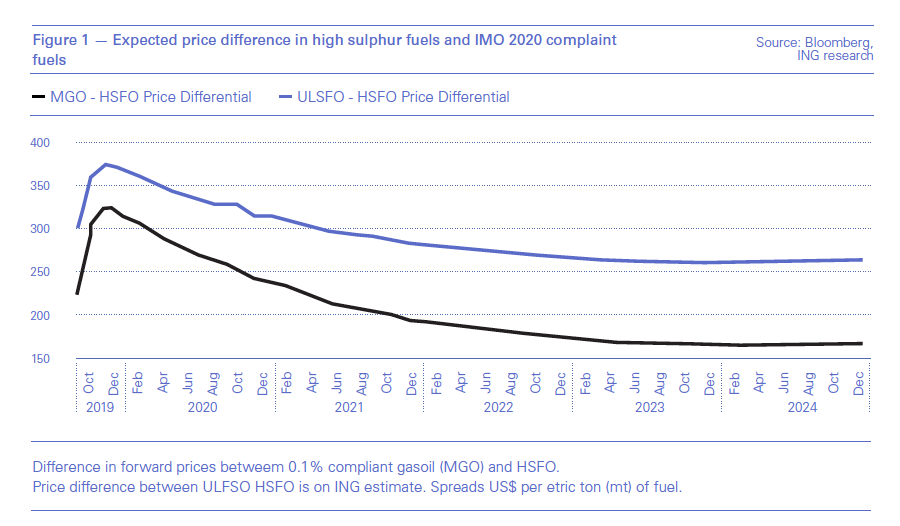

Even with the new cap just months away, an accurate forecast of the cost of using 0.5% compliant ULSFO blends is not available, complain the ING analysts, with reliable market forward rates yet to emerge. They therefore estimate the price spread of 0.5% ULSFO to standard high sulphur fuel oil at $165-300/metric ton.

The larger the price spread, the more attractive an investment in scrubbers and their operation – which uses extra fuel. Smaller vessels are highly likely to simply swap to low-sulphur fuel oil. LNG’s problem is that it requires an even larger investment than scrubbers.

Select group

The gas industry is pressing to prove that LNG is the most viable alternative. While it’s assumed that electric or hybrid powered vessels will play an important role in shipping in the future, current battery technology allows only short distances.

US engineers Black & Veatch CEO Steven Edwards, insisted at an industry event last year that while electric technologies are clearly the leader when it comes to the personal transportation transition, “LNG is right for maritime in particular.”

But it’s a case that’s struggling to gain traction.

“There are 55,000 ships of over 500 (metric) tons,” the general manager of the Society for Gas as a Marine Fuel (SGMF) Mark Bell noted. “Across that world fleet, around 0.2% -- or 140 ships -- are now running on LNG. A reasonable target appears to be to boost that to 2%, or 1,500 ships in the coming years.” The reason for that sluggish take up of LNG by the maritime industry is two-fold.

In the first instance, switching to LNG requires a more intensive -- and therefore costly -- conversion process compared with the other solutions. Engines must be fundamentally modified, if that’s even possible.

Hapag-Lloyd will spend $30mn converting the 15,000 twenty-foot equivalent units containership Sajir to LNG propulsion, the German shipper revealed earlier this year. On top of that are the lost earnings from the operation, which could take over 100 days.

Those vessels that are convertible must then be able to refuel, and LNG bunkering infrastructure is lacking and unavailable in most ports. This means they need a backup fuel tank, which reduces transport capacity and provokes balancing issues.

“The key is the availability of gas,” said Americas vice-president for Wartsila Marine Solutions John Hatley. “We’ve been building large gas engines since the 1990s, it’s proven technology, but the infrastructure has been an issue.”

While these issues are being worked out, LNG is likely to find itself serving a select group, at least initially.

Bell remains upbeat though. He pointed out that while his target to have 1,500 LNG-powered vessels plying the seas in the near future may not sound hugely ambitious, it would see annual demand from the shipping industry for LNG rise to match that of Japan. The world’s largest consumer currently uses 80mn-90mn mt/year.

But to expand its role in shipping more significantly, LNG must target large, new-build ships. “It depends on when we’re going to start seeing new container ships,” said managing director of Spanish utility Naturgy Joaquin Mendiluce. “Today there’s too many, but shipping companies are ready to analyse the opportunities regarding LNG when coming to that point.”

To seal that deal, though, infrastructure will have to be built in advance to allow bunkering. Edwards claims “ports around the world are looking at refuelling infrastructure,” but there’s a conundrum to solve.

“It’s a chicken and egg situation,” says the vice president for Canadian distribution utility Fortis LNG GP Gareth Jones. “You need the infrastructure, but to invest in that you need to make sure the customer demand is there.”

Long game

Concerns over a lack of preparation for meeting the IMO cap by competing suppliers may help push LNG’s case that it is a long-term solution. In particular, advocates point out that as the liquidity and transparency of the LNG market continues to grow, prices become more competitive and hedging becomes a possibility – a given in the marine gasoil market.

“Operating on LNG looks very attractive on a long-term basis,” says a Wartsila while paper, “while operating on HFO with after-treatment systems looks more attractive in the short term because of the lower investment costs”.

Questions over the capacity of global refiners to produce enough low-sulphur fuel oil to meet demand persist. KBC’s report showed that 40% of Middle Eastern and European refineries had not made the necessary adaptations for producing the lower sulphur fuels that the shippers will need.

That suggests that even those that can secure supplies will end up paying handsomely for the privilege. The cost of fitting scrubbers has also risen due to the heavy demand and producers say they can’t keep up.

Not all large ships will be using scrubbers, the ING analysts note, pointing at not only the lack of capacity and waiting lists at the major suppliers but also the “wait-and-see mentality of the industry” and the regulatory risks linked to environmental concerns. LNG is the cleanest option in these terms, with carbon emissions around a fifth lower than those of fuel oils.

Rather than competing in the ongoing rush then, LNG may be better playing the long game. Given the lack of capacity, the uncertainties, and an absence of clarity on enforcement of the regulations, not all shippers will comply with the IMO cap immediately.

To try to ensure compliance, it will be illegal for ships that are not fitted with scrubbers even to have high-sulphur fuel oil on board. But that only highlights the fact that the IMO, as part of the United Nations, has no authority to enforce the new guidelines. Instead, that power will fall to individual governments. At this point, the regulations have been endorsed by just 59 states. China, the world’s largest shipper and shipbuilder, has not signed up. Estimates of the rate of non-compliance differ hugely, ranging from as low as 10% of the global fleet to as high as 40%.

“It’s a huge opportunity,” Bell announces, pointing out that “the maritime industry is a notoriously slow adapter”.

Footing the bill

Whichever technology a shipper turns to in order to meet the new regulations, it will clearly raise costs significantly. Owners must either invest in scrubbers and the extra fuel to run them, pay the higher price for low-sulphur fuel oil, or sink money into LNG.

A jump in freight rates, which in recent years have been depressed by over capacity and price wars, is clearly on the cards. Who will cover these extra costs is a debate.

KBC suggests that “most ship owners will not (or cannot) invest in scrubbers.” The consultancy expects the cost of low-sulphur fuel oils to rise to more than 50% above high-sulphur products. The maritime industry insists that already low pricing means it can’t take these costs on board.

“If the extra costs related to low-sulphur fuel go to shipping companies and end there, it would result in bankruptcies,” Soren Skou told the Wall Street Journal in April. He is CEO of AP Moller-Maersk, the world’s biggest container ship operator by capacity.

That passes the buck to the cargo owner. ING says most shippers will try to pass through the raised costs to their clients. The investment bank estimates an average rise of up to 25% in freight rates.

However, KBC says it found in a survey that consumers are “mostly unwilling to pay the price of further reducing their personal ‘Sulphur Shadow”. If consumers resist, so too will cargo owners.

In that case, shippers may instead reduce speed. This would cut their fuel bills considerably, but also reduce the overall capacity of the global shipping fleet.

Yet even as the shipping companies, cargo owners and consumers try to come to terms with the new sulphur cap, new environmental regulation is due. From 2020, the focus in shipping will shift towards climate action. IMO members agreed in last year to cut carbon emissions by 50% in 2050 versus 2008.

The route to achieving those goals is far from clear, with the maritime industry yet to identify realistic technologies that could help it meet the 2050 target. Fuel efficiency and ship design are likely to offer some advances, say analysts. Biofuels and LNG are viewed as potential transitionary options. However, while LNG may offer the cleanest current solution, it would not meet the IMO’s 2050 target.

Synthetic fuels, methanol and hydrogen are eyed as the eventual potential solutions. However, all these technologies are at an early stage, and need significant research and innovation to prove if they’re technically and economically viable.

That leaves the shipping industry sailing in the dark for the meantime. The one point of clarity seems to be that ship owners face substantial investment demands in the coming years, and that consumers will need to foot the bill if they want to both protect the planet and enjoy the benefits of global trade at the same time.