What the global gas crisis means for the net-zero transition [Gas in Transition]

The following feature is based on a thought-provoking presentation by professor Dieter Helm at the FLAME Gas & LNG conference held in Amsterdam on May 2-4. He said that even though the energy crisis is not over yet, the big shocks have been dealt with.

Helm said crises tend to follow a cycle. “They start with denial, then panic when the end of the world seems nigh, then relief that all is not as bad as it seemed, followed by the long legacy as the full costs and impacts are gradually revealed.” Relief is often accompanied by complacency – declaring the crisis over too soon.

This crisis, caused by a mismatch between energy supply and demand, is still haunting Europe’s industries and economies. Even though gas prices have declined to very low levels, they are still over two-times higher than pre-COVID levels, as are electricity prices. With lower Russian gas supplies, China’s economy back to growth mode in 2023 – leading to a rebound in gas demand – and limited increase in global LNG supplies, next winter could still be a challenge, with energy prices becoming problematic again.

In Europe the crisis will be over only when it ensures a consistent, secure and competitive energy supply, it completes energy market reform and puts its economy back on a competitive footing.

The obvious lessons from this crisis affecting transition to net-zero are security of supply, the speed of the transition, the need for interconnected energy networks and the organisation of the electricity market – in other words, market design.

Obvious lessons

According to Helm, the first lesson to be learnt from the crisis is that “everybody should understand that the crisis has demonstrated that natural gas is essential to energy transition.” As the adoption of intermittent, low density, geographically dispersed renewables increases, gas becomes absolutely essential in providing flexibility and firm power. Technological developments and battery storage are not yet ready to deal with prolonged intermittency.

Another lesson is not to rely on Russia as a supplier of commodities – any commodities. That does not mean not trading with the Russians, but only as part of diversified supplies. This is where past German energy policy went catastrophically wrong.

But the most important lesson is the importance of security of energy supplies. Europe took this for granted. It was assumed that placing increasing reliance on intermittent renewables was the right way going forward. The process was even accelerated, as was divestment from oil and gas led by government policies and regulations and increasingly assertive climate change activism. Doing this without reducing demand and without dealing effectively with intermittency would exacerbate energy security problems.

This was stressed by BP CEO, Bernard Looney, in a recent, pragmatic, interview. He said: “There are people in society who certainly want to see the end of fossil fuels overnight,” but “when production falls and demand doesn’t change, there’s only one thing that’s going to happen: prices are going to go up.” He warned “The price of gas went up 10 times when we lost 3% of the world’s gas supply — and who wants to deal with that economic, financial crisis, cost of living crisis?”

It was mistakenly assumed that intermittency would be taken care of by Europe’s energy system. But low wind speeds and drought challenged wind energy, hydro and nuclear. The energy system was found wanting and gas had to come to the rescue. In the run-up to Ukraine’s invasion by Russia every thing that could go wrong with security of energy supply did – intermittent electricity was found wanting. Evidently, and obviously, it is not possible to rely on everything working all of the time.

It was mistakenly assumed that intermittency would be taken care of by Europe’s energy system. But low wind speeds and drought challenged wind energy, hydro and nuclear. The energy system was found wanting and gas had to come to the rescue. In the run-up to Ukraine’s invasion by Russia every thing that could go wrong with security of energy supply did – intermittent electricity was found wanting. Evidently, and obviously, it is not possible to rely on everything working all of the time.

The importance of security of energy supply is vastly more important now than it was 10-20 years ago because of the increasing reliance on IT and AI. The entire information technology system relies on the reliability of dependable electricity supply. This is absolutely crucial to the functioning of society and industry – all crucial infrastructure is electricity-dependent. If it goes down, disruption can be massive. Cutting off electricity can disable the economy, something that makes security of energy supplies that much more important. This requires building-in sufficient redundancy to withstand all possible disruptions.

Until the world is able to deal with intermittency dependably and reliably, it will need diversified energy supplies, including natural gas and all other energy sources – not just for the next few years, but for a considerable length of time.

Also important to security of energy supplies is interconnection – both for electricity and gas. The more widespread interconnection is, the greater the security of supply.

Electricity market design

The commodity-based market design systems developed in the 20th century are not applicable to the 21st century’s net-zero systems based on increasing use of intermittent renewables and the growing role of zero marginal costs. What is needed is a framework that reflects zero marginal costs and ensures security of energy supplies.

It becomes critical to deliver sufficient firm power equal to the expected total peak demand, plus a security margin, to meet security of supply requirements. The question then is how do you translate that requirement onto a market design fit for the net-zero transition.

As long as intermittency remains a problem, it is not certain that the EU's forthcoming reform of its electricity market design will capture these requirements, unless it deals with intermittency. The proposed reforms are designed to accelerate a surge in renewables and the phase-out of gas.

They introduce measures to incentivise longer-term contracts with non-fossil power production and bring more clean flexible solutions into the system to compete with gas, such as demand response and storage. Both are important in reducing energy demand and reliance on fossil fuels, as well as addressing intermittency.

These measures are also designed to improve the flexibility of the power system. But it will take time to deal effectively with intermittency and until this happens gas has an important role to play.

Implications for natural gas

The energy crisis of 2022 propelled energy security as the top concern of policy-makers and industry, with major economic and geopolitical Implications and potential impact on energy transition.

As energy transition progresses, with the building of huge renewable power generation capacity, gas-fired generation is rendered intermittent too – it is used only when renewable electricity is not available – making its economics difficult and creating new energy security risks. Because of renewable power intermittency, the need for flexible sources of electricity to maintain firm power increases.

That means that there must be strategic reserves of gas ready and available as an essential part of transition to net-zero – a process that will take time.

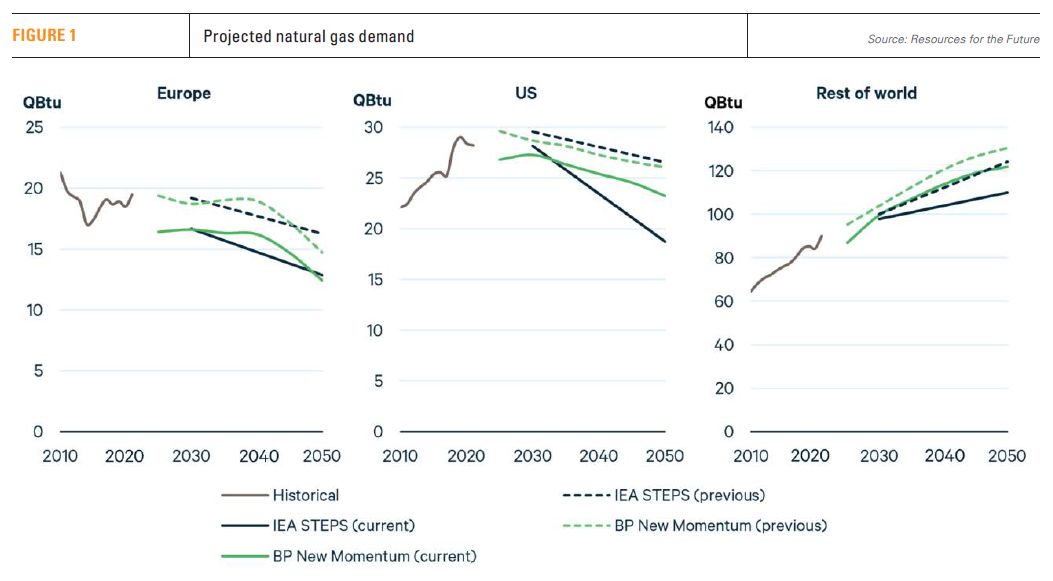

The International Energy Agency (IEA) shares this view. It considers natural gas to be “one of the mainstays of global energy.” It has a durable role in energy transition. This is also supported by BP and IEA Outlooks (see figure 1) that show natural gas demand remaining high to 2050, particularly in the world but also in the EU and the US.

The G7 ministers’ meeting communique on climate, energy and environment - held in Japan on 16 April – recognised this when it said that investment in the gas sector "can be appropriate" to address potential market shortfalls provoked by the crisis in Ukraine, if implemented in a manner consistent with climate objectives.

This was confirmed on May 21 by the G7 leaders at their summit in Hiroshima. Referring to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the energy crisis, the G7 leaders emphasised the “important role that increased deliveries of LNG can play.” They also said that “publicly supported investment in the gas sector can be appropriate as a temporary response” to the crisis.

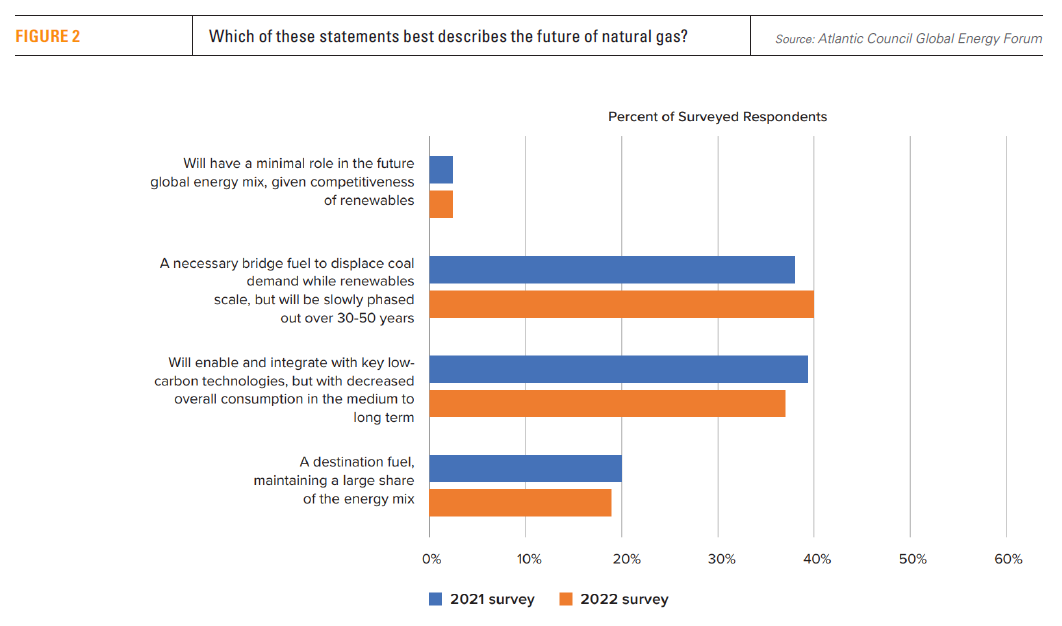

Based on an opinion survey of “of the global energy policy community, including contributions from leaders in governments, the private sector, and expert communities,” the Atlantic Council commented that: “The events of 2022 illustrate how instability in conventional energy markets can weigh on the global economy and impact the public debate about how best to pursue an inclusive and equitable energy transition. Global upheaval in natural gas trade over 2022, did little to dissuade respondents of natural gas’ utility to global market stability. Respondents to the 2022 survey continue to see a long-term role for natural gas.” (see figure 2)

A smooth transition to net-zero will require synchronisation between the ability to provide firm and reliable clean energy and investments to maintain the required supply of oil and gas. Under-investments lead to high prices and force financial institutions and international oil and gas companies to divest from the sector, without a commensurate reduction in demand, transfers production to national oil companies.

This has proved a difficult balance to strike, especially in Europe where the drive to accelerate energy transition has been fast and furious over the last few years. And with intermittency still unresolved, perhaps too fast.

This has led to a political pushback on the European Commission’s (EC) green agenda, forcing EC’s president, Ursula von der Leyen, to say that the EU needs to assess its capacity to absorb multiple new environmental laws. The French president, Emmanuel Macron, went further. He called, in early May, for a “regulatory break” on EU green law to allow industry to digest the large quantity of regulation that has been pushed through.

Manfred Weber, the leader of the European People’s party, the largest in the European parliament, suggested that it is time to “to reflect on the scope and speed of this process. If climate wins and the rest of society loses, we will not achieve net zero.”

In addition, as the IEA points out, reaching net-zero emissions requires a complete transformation of how people power their daily lives and the global economy. But changing people’s way of life comes at a cost, raising affordability and fairness issues, and will take time.

At present, the world is underinvesting in all forms of energy, not just in oil and gas. The pace of technological development and deployment is still far behind what is needed to accelerate energy transition. According to Bloomberg and the IEA, annual clean energy investment needs to increase by a factor of three in order to get back on track to net zero.

At present, the world is underinvesting in all forms of energy, not just in oil and gas. The pace of technological development and deployment is still far behind what is needed to accelerate energy transition. According to Bloomberg and the IEA, annual clean energy investment needs to increase by a factor of three in order to get back on track to net zero.

Nevertheless, transition to net-zero, energy security and access to energy are intertwined issues that must be addressed urgently and simultaneously. This requires careful planning. Energy transition risks losing public support if it comes at the price of economic disruption. This is especially so for developing countries that need to find ways to secure energy supplies, while decarbonising their economies and while continuing to raise living standards.

As BP’s Looney pointed out, while doing so, “there is an issue called carbon…It’s a real issue. It needs to be tackled, and that’s why we want to transition.” Transition to net zero requires a major reduction in energy emissions. COP28 will be the place where the oil and gas companies will show how they plan to deal with emissions.

As Helm said, we now have the opportunity to reform energy markets and take security of supply seriously. Let's hope that the required reforms are carried out, rather than require another energy crisis like the one we have been enduring since the summer of 2021.