Weighing up the LNG emissions footprint [Gas in Transition]

In the space of less than a year we had two major legislations developed and are on their way to be enacted into law by the US and the EU to reduce methane emissions.

In early May, the European Parliament (EP) approved new legislation with tighter rules to reduce methane emissions in energy, a sector that accounts for about 20% of EU’s methane emissions. It is designed to ensure transparency and consistency in the measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) of LNG emissions, as well as introduce more stringent leak detection and repair (LDAR) requirements to tackle leaking infrastructure. The parliament also asked the European Commission (EC) to ensure that exporting countries abide by similar rules.

This was preceded by the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), approved by the US Senate in August 2022, that includes a ‘Methane Emissions Reduction Program.’

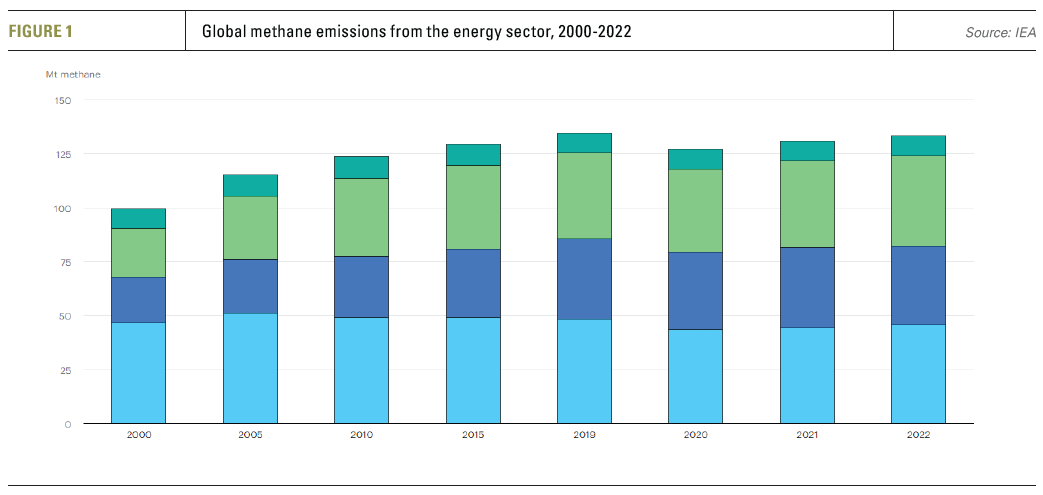

This is timely. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reported, in its Global Methane Tracker 2023 report, that the global energy sector was responsible for nearly 135mn metric tons of methane emissions in 2022, a slight rise from the amount in 2021 (see figure 1).

The IEA estimates that “in the oil and gas sector, emissions can be reduced by over 75% by implementing well-known measures such as leak detection and repair programmes and upgrading leaky equipment.” Furthermore, “based on average natural gas prices from 2017 to 2021, we estimate that around 40% of methane emissions from oil and gas operations could be avoided at no net cost because the outlays for the abatement measures are less than the market value of the additional gas that is captured.” IEA’s report includes recommendations and an actionable roadmap for curbing methane emissions.

Emissions of methane during oil and gas production and supply are a serious contributor to climate change. Methane is over 80 times more potent that CO2 over a 25-year timeframe and 28 to 36 times more potent over 100 years.

Given that methane’s atmospheric lifespan is around 10 years, much less than that of CO2, actions to reduce methane emissions now can have a faster impact on the rate of temperature increases than actions on carbon dioxide. Hence the urgency.

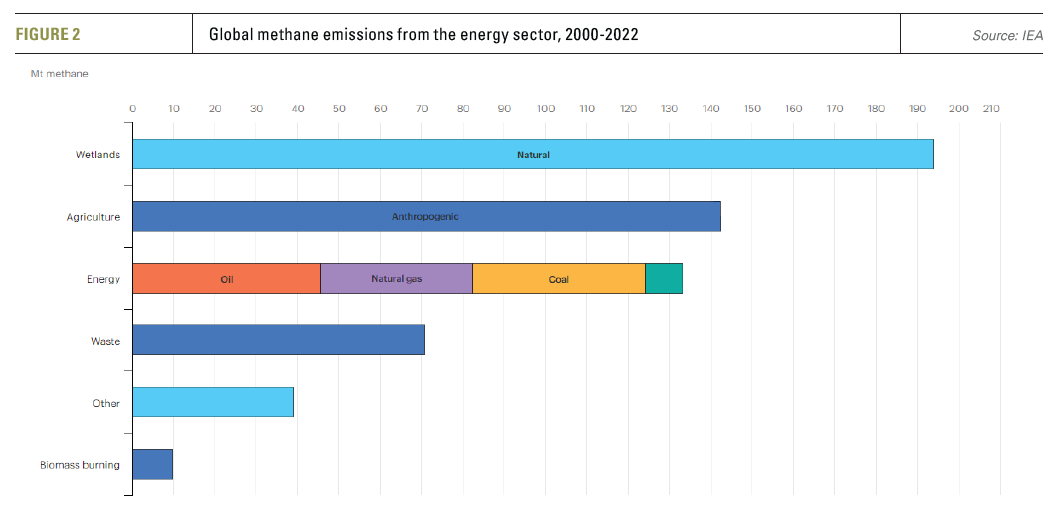

The IEA estimates that the energy sector is responsible for about 23% of global methane emissions (see figure 2).

The IEA is warning that methane emissions are increasing faster than ever. Today, they are 2.5 times higher compared to pre-industrial levels and are responsible for 30% of the rise in global temperatures since then. This demonstrates the urgency of taking action to reduce them.

EU methane reduction legislation

The EU focused its methane reduction legislation on the oil and gas sector, responsible for 19% of Europe’s methane emissions, as the relatively easier route to introduce such regulation. The agriculture sector, which is responsible for 53% of EU methane emissions, or waste, responsible for 26%, are politically much more sensitive and require much more careful handling.

The European Council had already agreed new rules in December 2022 that require oil and gas operators “to carry out surveys of methane leaks in different types of infrastructures at set intervals, using devices with proposed minimum leak detection limits, detect and repair methane leaks.”

Venting and flaring, which release methane into the atmosphere, will be banned except for narrowly defined exceptional circumstances, like construction, repair, decommissioning, safety or testing of the components. Member states will also have to develop mitigation plans to remediate, reclaim and permanently plug inactive wells and temporarily plugged wells.

There was also a requirement for methane emissions of EU's energy imports to be traced, by putting forward “global monitoring tools that will increase transparency of methane emissions from imports of oil, gas and coal into the EU.” These would allow the EC to consider further actions in the future.

There was also a requirement for methane emissions of EU's energy imports to be traced, by putting forward “global monitoring tools that will increase transparency of methane emissions from imports of oil, gas and coal into the EU.” These would allow the EC to consider further actions in the future.

These rules were the basis of the legislation proposed and approved by the EP, with some tighter rules for monitoring emissions. The Parliament requires companies operating fossil fuel infrastructure to check for leaks as often as every two months. In addition, gas infrastructure operators must replace or repair all methane-leaking components immediately upon detection or within a maximum of five days.

EP’s legislation also includes rules for accurate measurement, reporting and verification of methane emissions in the energy sector, as well as for the abatement of those emissions, and extends these rules to the petrochemical sector. It proposes third party verification to ensure greater independence and transparency, requiring that transparent information on methane emissions should be made available to the markets.

But the most significant change is extending the rules to apply to imports of oil and gas. From 2026, those importing oil and gas into the EU will have to prove that they are adhering to these requirements, especially MRV and methane mitigation. Gas and LNG imports from countries with comparable laws will be exempted.

Given that the EU imports 97% of its oil and 90% of its natural gas consumption, extending the rules to apply to imports of oil and gas, if approved by the European Council, would be a major development and would contribute to reducing methane emissions globally.

In addition, the EC has been asked to propose by 2025 a binding methane emission reduction target for all relevant sectors by 2030. Member states should then set national reduction targets as part of their integrated national energy and climate plans.

It is important that this legislation succeeds. Otherwise, without effective measures in place to reduce methane emissions, Europe will miss its 2030 climate targets.

In a rare convergence of views, Eurogas, industry groups and green campaigners all have expressed support for EP’s proposed legislation.

These will now need to go back to the European Council, which is likely to make changes before final approval. Once approved, expected this year, this will become EU’s first major legislation to reduce methane emissions.

Impact of the IRA on emission monitoring

The US has gone further. In addition to emission monitoring and mitigation, the IRA has introduced a charge on methane emitted by oil and gas companies who report emissions under the US Clean Air Act, starting at $900/mt for emissions reported in 2024, rising to $1,200/mt in 2026 and $1,500/mt in 2027 and thereafter. This charge will apply to facilities with methane emissions that exceed 0.2% of the natural gas sent to sale from such a facility, or exceed 25,000 mt of CO2 equivalent/year. Making methane emissions expensive is expected to play a critical role in curbing them.

It has been estimated that the Act could lead to a reduction in US greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 40% below 2005 levels by 2030.

The IRA was followed in November 2022 by a proposal for the regulation of methane and volatile organic compounds from new facilities, as well as methane from existing oil and gas facilities, issued by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It requires routine monitoring of all oil and gas well sites and facilities, for their entire life, and repair of all fugitive emissions – including orphaned and unplugged wells.

The proposal introduced a ‘Super Emitter Response Program’ (SERP), allowing approved third-parties to deploy continuous monitoring systems, satellite surveillance, and drone and airplane surveys to produce data on methane emissions. These monitoring technologies would need to be approved by the EPA. Operators would then be notified and will be required to remediate any emissions. The time to be allowed for notification and remediation is still to be defined.

The US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has also introduced a ‘waste prevention rule’ to prevent methane waste and loss of natural gas at oil and gas lease sites on public lands.

The Biden Administration is aiming to finalise these rules and regulations before COP28 in November, aiming also to make it harder for a new administration to roll them back.

Global Methane Pledge

Together, the US and the EC took a leading role in the Global Methane Pledge (GMP) initiative, launched at COP26 in 2021. It “aims to catalyse global action and strengthen support for existing international methane emission reduction initiatives to advance technical and policy work that will serve to underpin Participants’ domestic actions.”

Since its launch, OGP has generated strong momentum for methane action, with 150 countries endorsing its goal to reduce global methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Many of these countries are expected to enact tighter regulations and new guidelines for reducing methane emissions.

With the US and the EU putting in place detailed rules for the reduction of methane emissions, it is hoped that other OGP signatories will follow their lead. Otherwise, they will not be able to achieve their 2030 goal. There is also the additional incentive that gas and LNG imports to the EU from countries with EU-comparable laws will be exempted.

The forthcoming Methane Mitigation Global Summit, to be held in June in Houston, will provide an insight into regulations, commitments. methods and innovations to tackle oil and gas methane emissions globally.

Going forward

US and EU policymakers appear to be coordinating their respective methane reduction regulations, but alignment is not yet clear. It is hoped that such coordination will eventually lead to the development of uniform standards. This should then make it easier to extend such regulations to the other big methane emitting sectors, not just energy.

With emission monitoring gaining traction, a number of companies are developing systems based on satellite networks equipped with sophisticated cameras to monitor methane leaks and emissions from space, or by using drones. The threat of fines and preference for verifiable and certifiable ‘cleaner’ gas is spurring investment and deployment of such systems, with increasing oil and gas company support. With such systems now becoming available to all, regulators, operators and to the public, they are ushering in a new era of emission monitoring, reliability and transparency, but also accountability.

With emission monitoring gaining traction, a number of companies are developing systems based on satellite networks equipped with sophisticated cameras to monitor methane leaks and emissions from space, or by using drones. The threat of fines and preference for verifiable and certifiable ‘cleaner’ gas is spurring investment and deployment of such systems, with increasing oil and gas company support. With such systems now becoming available to all, regulators, operators and to the public, they are ushering in a new era of emission monitoring, reliability and transparency, but also accountability.

The UN launched its own high-tech, satellite-based, global methane detection system at COP27. The ‘Methane Alert and Response System’ (MARS) is a new initiative “to scale up global efforts to detect and act on major emissions sources in a transparent manner and accelerate implementation of the GMP.” The UN intends to use this “to alert governments, companies and operators about large methane sources to foster rapid mitigation action of this potent gas.”

With 90% of its natural gas imported, sooner than later the EU will prioritise obtaining its gas from ‘cleaner’ sources. But it is not clear how and when gas and LNG suppliers will be able to meet such requirements. And given security of energy supply concerns, it is also not clear whether the EU and European countries are ready to move in that direction. Nevertheless, it is something that will happen, likely by 2026.

There are also many concerns about verification and acceptability of standards where gas changes hands – where the producer, liquefier and supplier are different parties, as is the case with US LNG. There is some way to go before such systems can be put in place and can be applied effectively.

But what is positive, is that, with the US and the EU determined to put in place appropriate regulations, it should be possible to achieve a substantial reduction in global methane emissions from the energy sector within this decade.