Vaca Muerta changes Argentina’s gas game [NGW Magazine]

Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale gas formation is at the centre of an energy revolution taking place in the South American country.

Economic motives supporting that energy revolution appear to have taken priority over any negative impacts such activities will have on the environment. Considering uncertainties related to inflation, the currency and energy prices in Argentina, the government’s decision to support the development has been an easy one.

Continued development of Vaca Muerta will be a game-changer and allow Argentina to: multiply its oil and gas reserves by factors of five and 14, respectively; sell oil and gas to the world; activate all of its productive sectors; generate 500,000 direct and indirect jobs by 2024; and fulfill its energy demand for 150 years, according to Argentina’s ministry of production and labour.

“Vaca Muerta is a positive energy revolution,” Argentine president Mauricio Macri said in October during a ceremony in Neuquen province which sits above the gasfield. In a speech broadcast by Argentine media outlet La Nacion, he said: “We are not going to stop until we have exported $30bn in gas and oil from Vaca Muerta.”

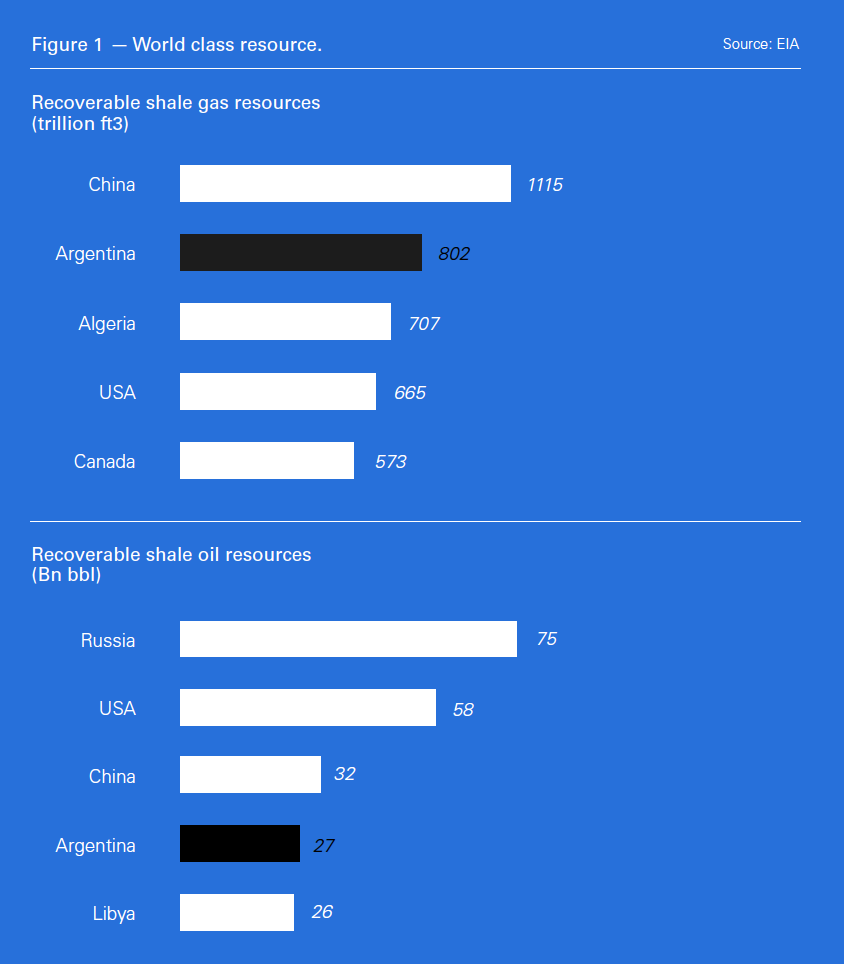

Argentina is among a list of only four countries, including the US, Canada and China, that commercially produce shale oil and gas. And while shale gas production is in its infancy, a boom could be forthcoming, given the size of the prize: according to a US Energy Information Administration (EIA) report published in 2013, Argentina holds the world’s second largest recoverable shale gas resources, at 802 trillion ft³, and the fourth largest recoverable shale oil resources, at 27bn barrels.

Vaca Muerta encompasses more than 35,000 km² in four Argentine provinces: Neuquen, La Pampa, Rio Negro and Mendoza. The formation contains 40% of Argentina’s unconventional gas and 60% of its unconventional oil, and contains more unconventional gas than Russia and more unconventional petroleum than Venezuela, according to Argentina’s government.

However, Vaca Muerta’s development will not come without opposition. For government, debate has been purely economic. For green groups, the debate has focused on the impact that shale gas development will have on climate change, and most of that debate has focused on fracking.

“We’re talking about climate change and a global phenomenon,” Barbara Gottlieb, director of environment and health programs for Physicians for Social Responsibility in Washington, DC told NGW. “We’re talking about changes in land mass, temperatures, and ocean temperatures. The scale of the problems goes way beyond any national border and should be of concern to people in Argentina.

But so far, and happily for the government, these concerns have not been obvious. Alvaro Rios Roca, managing partner at consultancy Gas Energy Latin America, told NGW Argentina has many of the same concerns as those facing the US surrounding fracking: the need for water, the disposal of flowback water, and the desire to avoid aquifer contamination. But those concerns, he said, don’t move the needle much in the arid and lightly-populated Vaca Muerta.

But so far, and happily for the government, these concerns have not been obvious. Alvaro Rios Roca, managing partner at consultancy Gas Energy Latin America, told NGW Argentina has many of the same concerns as those facing the US surrounding fracking: the need for water, the disposal of flowback water, and the desire to avoid aquifer contamination. But those concerns, he said, don’t move the needle much in the arid and lightly-populated Vaca Muerta.

“Opposition to fracking isn’t an issue there or in Argentina,” he said. “In addition, it’s creating thousands of jobs and the activity gets local support.”

As a result of rising shale production, Argentina expects to save an estimated $400mn by not importing LNG and pipelined oil and gas in 2018. More important, after 11 years the country will again export gas to Chile, according to the government.

In August 2018, Argentina’s production of oil in Neuquen reached 120,551 b/day, while gas production reached 69.8mn m³/day, the Neuquen government reported in an official statement on its website. Of that, unconventional oil amounted to 65,185 b/day, while unconventional gas amounted to 43.2mn m³/day.

In five years, Argentina expects combined unconventional oil and gas production to reach 260mn m³/day, of which 100mn m³/day would be destined for export. Likewise, Argentina expects to be a new exporter of gas by 2021, Argentina’s former energy minister Juan Aranguren said during a presentation in Houston in May 2018.

And if the energy secretariat achieves its targets for unconventional oil and gas production between 2018 and 2023, development of the Vaca Muerta could generate at least $1.4bn/year in direct activity for national oilfield suppliers.

That surge in economic activity will be felt not only in Anelo, a small town in Neuquen that has become Vaca Muerta’s operating centre; but all across Argentina as demand for products and services soars.

Geologically, Vaca Muerta compares favourably with both the Eagle Ford and Marcellus shale plays in the US: its shale beds are about 305 m thick; Eagle Ford’s are 76 m and the Marcellus beds just 61 m, according to data from G&G Energy Consultants.

Typical Vaca Muerta wells take 37 days to drill, at costs ranging between $10mn and $12mn, according to the Argentine ministry. Over the next 30 years, it said, investment could reach $250bn if the field is developed as expected.

However, that level of investment could be deterred by issues related to high drilling and completion costs and infrastructure restraints, among others. “Moreover, to fully exploit the resources, there would be substantial need of not just capital, but also skilled workers and advanced technology,” consultant Deloitte said in a report on its website.

Argentina is on the right path to make large-scale development of Vaca Muerta a reality. Responsible development of its unconventional resources has potential to be a once-in-a-lifetime economic engine for the country, said Clay Neff, president of Chevron Africa and Latin America Exploration and Production Company, in an official statement last month.

However, “a stable and predictable business environment is essential to draw the investment capital needed to ensure Vaca Muerta reaches its potential,” he added