US targets methane emissions at home and abroad [Gas in Transition]

The administration of US President Joe Biden has set its sights on reducing methane emissions – both on the domestic level and internationally. In September, the US and the European Union jointly committed to cutting global methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030 compared with 2020.

Unveiling their Global Methane Pledge initiative at the Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate, they called on other countries to join them. Argentina, Ghana, Indonesia, Iraq, Mexico and the UK were among the first to sign up, along with Italy, whose commitment came on top of the EU-wide adoption of the pledge. By mid-October, 24 more countries, including nine of the world’s top methane emitters, had joined the initiative.

However, pledging to cut methane emissions will still need to translate into concrete action, and it is not yet known what this will look like. Additionally, progress on methane emissions cuts by some countries could be offset by others that treat the issue as less of a priority and do not sign up to the US-EU pledge.

“The leading countries in approaching and implementing any of these changes are mostly OECD countries, with some non-OECD also seriously involved, but overall, there is the countering case of emerging economies, which are expected to remain dependent on fossil fuels, contributing to methane emissions,” GlobalData oil and gas analyst Miles Weinstein tells NGW.

Despite this, having even some countries pursue steeper cuts to methane emissions could make a difference.

“Achieving verifiable methane emissions reductions anywhere is helpful for decarbonisation because it slows the rate of warming and buys time for new decarbonisation technologies and policies to take hold,” Ben Gilbert, an assistant professor of economics and business and faculty fellow at the Colorado School of Mines’ Payne Institute for Public Policy, tells NGW.

Challenges

The US-EU pledge has provided few details on what moves they will take, though it did identify several sectors – including oil and gas, coal, agriculture, and landfills – that accounted for significant levels of methane emissions. They also acknowledged a “global data gap” as far as methane emissions go. According to the joint statement, the EU will support the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) in establishing an independent International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO) to address this gap.

“One area where international coordination can help is in the development of standards for methane quantification that incentivise innovation in, and incorporation of, new methane detection and measurement technology,” says Gilbert.

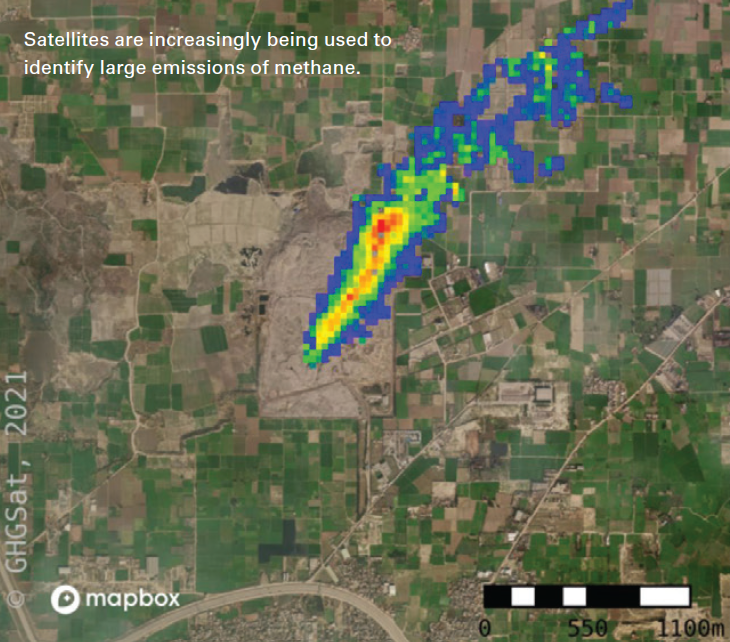

Currently, there are no international standards, and plenty of questions over the accuracy of existing statistics on methane emissions. Claims that methane emissions are higher than what is officially being reported have been emerging across several countries in recent years.

Currently, there are no international standards, and plenty of questions over the accuracy of existing statistics on methane emissions. Claims that methane emissions are higher than what is officially being reported have been emerging across several countries in recent years.

This includes the US, where data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), among others, has been called into question.

“EPA statistics on methane emissions are quite possibly inaccurate due to their reliance on emission factors, which are estimates, rather than actual emission measurements,” says Weinstein.

“A lot of the government statistics are based on what are called ‘bottom-up’ or ‘inventory-based’ methods, where someone counts the number of different types of equipment in use and frequency of various production activities, and applies an emissions factor to each piece of equipment and each activity,” says Gilbert. “A problem with the inventory-based approach is that often, through operator error or equipment malfunctions, these components emit at a much higher rate than the assumed emissions factor,” he continued. “Under current inventory-based practices it does seem that total emissions are underestimated. This is why it’s unclear whether emissions goals can be met if reductions are not verified using monitoring technology.”

On the other hand, many in the oil and gas industry have noted that so-called top-down methods of quantifying emissions, referring to the use of aircrafts and increasingly satellites, can also overstate emissions. When attempting to quantify emissions from a specific sector, emissions from other sources can also be included, potentially skewing the data. Top-down reading can also vary depending on the time of day the surveys were undertaken, potentially coinciding with peak emissions from field activity.

Next steps

Solutions may be coming soon. According to the US-EU statement, the European Commission will propose legislation this year to measure, report and verify methane emissions, as well as put limits on venting and flaring and impose requirements to detect and repair leaks.

The US, for its part, said it was pursuing methane reductions on “multiple fronts”. Part of this entails reinstating regulations that had been brought in by former US President Barack Obama, but subsequently rolled back by his successor, Donald Trump, who left office in January. Indeed, Biden issued an executive order relating to methane emissions on his first day in office, and the EPA is now developing new regulations, as various measures are being advanced through Congress.

One notable proposal involves the introduction of a fee on methane emissions stemming from oil and gas production. GlobalData noted in a press release in July that major oil and gas operators appeared to be generally supportive and co-operative when it came to both state and federal policy on climate action. However, Weinstein warns that it now seems the industry is “not willing to go as far as supporting a price on carbon or methane emissions.”

The proposal that cleared the House Energy and Commerce Committee in September would charge oil and gas companies $1,500 for every metric tonne of methane emitted. The American Petroleum Institute (API), an industry group, has criticised the proposal as being “duplicative” and “punitive”, and is lobbying against it. The measure is part of a broader legislative package that will need the support of the overwhelming majority of House Democrats, as well as all 50 Senate Democrats, in order to pass.

If the bill does pass, however, this would help the US to advance towards its methane emissions reduction goal. GlobalData has found that while oil and gas companies are already pursuing decarbonisation targets that include cuts to emissions, at least some government intervention is generally needed to help advance such aims.

“If the proposed methane fee were passed into law, it isn’t hard to imagine that it may come with real emissions measurements at facilities rather than the current estimates,” says Weinstein. “This would certainly be a more comprehensive and effective incentive than the current regulation.”

Gilbert, meanwhile, notes that a lot depends on the mechanics of how a fee would be implemented and how emissions would be accounted for.

“Some firms are investing in new equipment and processes that can reduce emissions and verify those reductions,” he says. “A rational system would reward those firms in order to create incentives for other firms to follow suit. A two-tiered fee might be one such example, where firms that verify their emissions using monitoring technology pay a lower fee than firms that don’t.”

Under Obama, the US had a previous target – a 2016 pledge to cut methane emissions by 40-45% by 2025. Weinstein notes that this was not on track to be met, which comes as no surprise given the regulatory rollbacks under Trump. The 2030 target, meanwhile, is not necessarily out of reach – domestically or globally.

“A large amount of methane emissions can be eliminated or reduced very inexpensively,” says Gilbert. “The cost curve for emissions reductions doesn’t start to get very steep until you’ve removed about two-thirds of the emissions.”

Tackling methane emissions has been dismissed by some as the “low-hanging fruit” of the energy transition, however.

“In the bigger picture, methane contributes only 17% of global GHG emissions on a CO2-equivalent basis, compared with about 75% from CO2,” said Weinstein. “On the other hand, reducing methane emissions involves improving infrastructure and operational practices so that flaring, venting, and leaking are minimised or fully eradicated. All of this requires a mix of regulations and incentives that lead to the necessary investment for efficiency in natural gas production, transportation, processing and storage,” he adds.